A Photographer’s Poignant Love Poem to Home

This is the second article in a three-part series exploring the meaning of home in modern China. It is being published to coincide with the Spring Festival, when millions of people across the country return to their hometowns to celebrate the holiday. Read the first article here.

In 1985, when Muge was 6 years old, his parents took him on a trip that he still savors today. The photographer, who is now 42, had never left his township of Jianshan, in the lush mountains of northern Chongqing, a province-sized municipality in Southwest China.

The family took a six-hour bus through the steep and luxuriant valley to Yunyang, a county on the Yangtze River and one of Chongqing’s most prosperous towns, to purchase a television. “That was my first time seeing the outside world,” Muge says. “I was so curious about everything that I still remember all the details vividly.”

The excursion left such a lasting impression on the boy that, 15 years later, when Muge returned home from Chengdu, capital of neighboring Sichuan province, for Lunar New Year as a newly minted college freshman, he made a deliberate detour to check out Yunyang. To his dismay, the place from his memories no longer existed. A large part of Yunyang had been demolished to make way for the reservoir of the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest hydropower project, and its residents had to move to new homes on higher ground 30 kilometers away. “At once, your memories are cut off,” he says.

In the next four years, as Muge — he uses his given name as his artist’s name — pursued a degree in broadcasting and television directing, the slowly filling reservoir submerged town after town along the Yangtze River, erasing more and more of his fond memories from childhood. More than 1 million residents had to be relocated for the project’s construction.

This collision of childhood recollections and present-day upheaval spurred the photographer to initiate his project, “Going Home,” in 2005. “I wanted to collect the places that were in my memories,” Muge says.

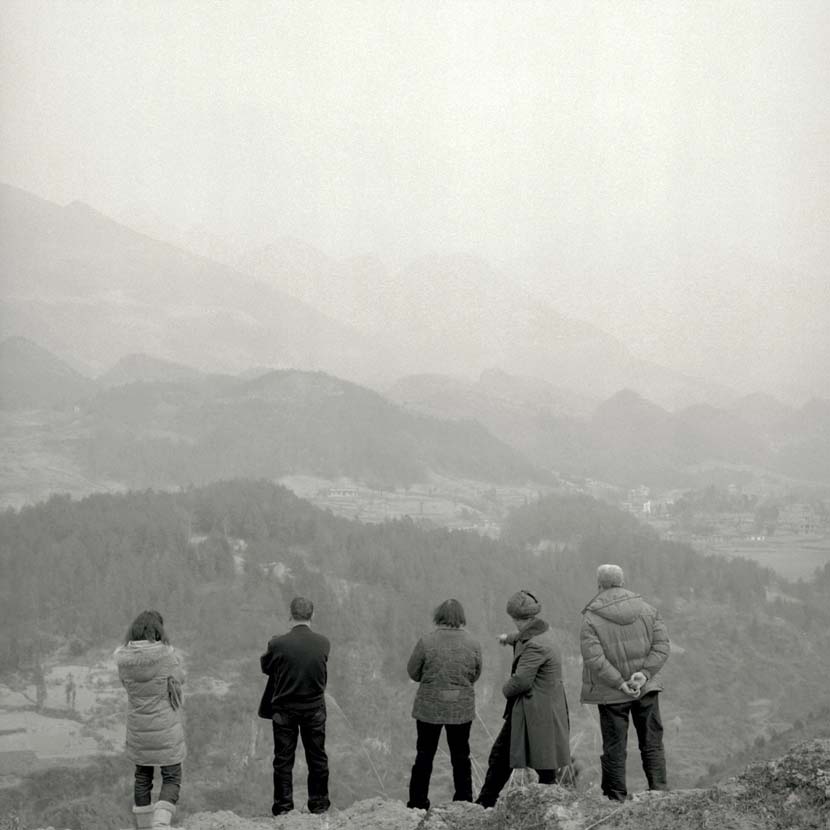

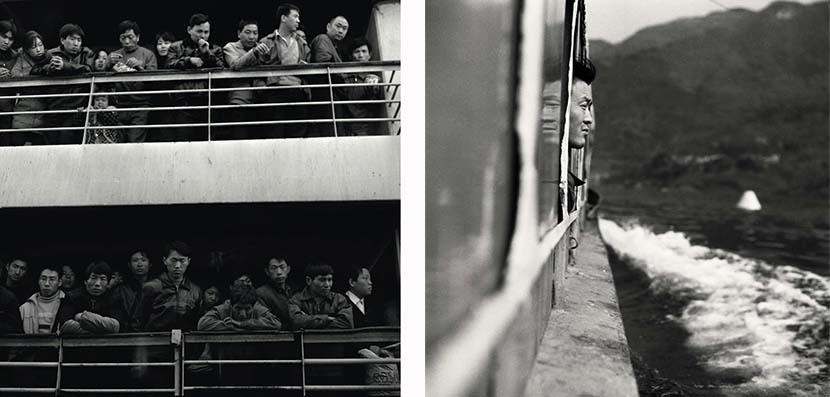

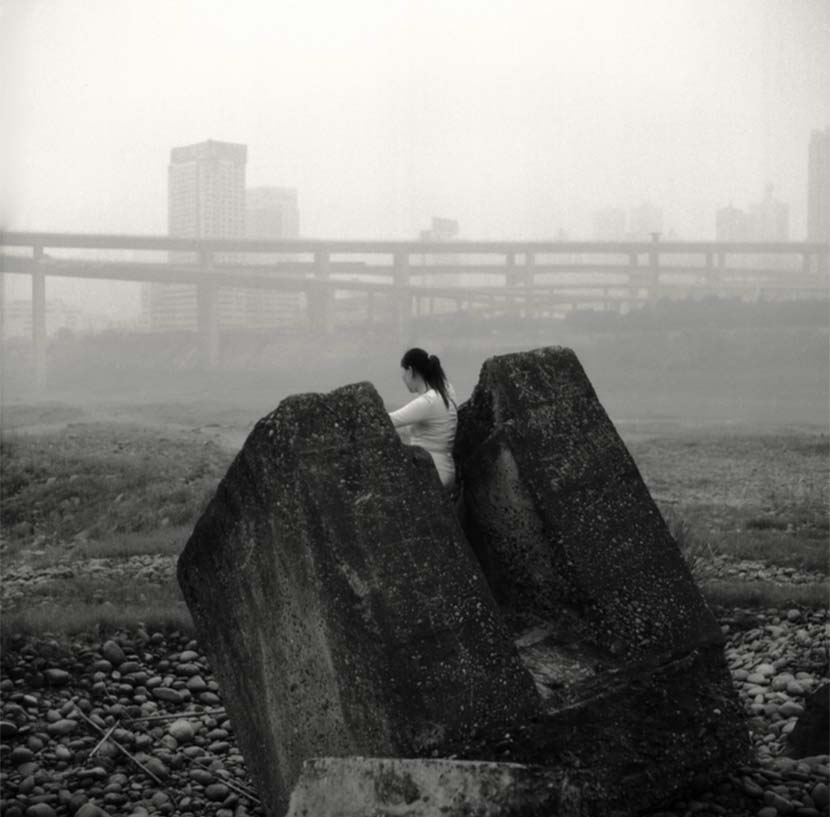

With Muge’s melancholic and poetic rendering of reality, his images look almost timeless, and his subjects stoic and lonely, as if disoriented by the expeditious changes around them. A couple warms up near a bonfire on a hill of rubble. A cook stands behind a makeshift, riverside noodle shack in a luminous fog. A man sits on his motorbike, pensively staring into the camera, a cigarette between his fingers. “They don’t like to complain too much, and everyone is quietly enduring their own hardships,” Muge says. “This is one of my deepest impressions of the Three Gorges people.”

Much has changed since Muge first embarked on “Going Home,” now in its 16th year. When he attended university, the journey between his college in Chengdu and his hometown Jianshan could take up to four days and require multiple means of transportations including bus, boat, and train. Today, Muge can drive home from Chengdu, where he still lives, in under 10 hours. The photographer has also gone from unknown to critically acclaimed, receiving nods in prestigious publications such as The New Yorker and being widely exhibited at international photography festivals and galleries.

According to Muge, the project is not a criticism of the Three Gorges Dam, but rather a personal reflection on the impact of rapid development on people’s ancestral homes, where culture and tradition are carried on for generations. “I don’t think demolition is necessarily bad. It depends on what the region needs to develop further. But it disrupted people’s ways of life,” Muge says. “A city might ordinarily take two or three decades to build, but after the (Three Gorges Dam) project, it takes only five to 10 years for a rudimentary village to be urbanized.”

For Muge, home is an emblem of perpetuity while his country is in a constant state of prowling forward. It is on his journey home that the photographer reminisces about the past and longs for stability. “I hope I will always have the desire to go home, the desire to return to familiar places,” Muge says.

Speaking to Sixth Tone by phone from his apartment in Chengdu, Muge discusses the background of his project, his affinity for the Yangtze River, and his reflections on home in an ever-changing China. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: Your hometown Jianshan is close to the Yangtze River. What was it like growing up there, and how was the relationship between the area’s residents and the river?

Muge: Life in a small town was actually relatively simple. When we had time, we went to nature and connected with the landscape, swimming in the summer, hiking in the winter. I think some of my most beautiful memories came from nature, its mountains and waters. When people living along the Yangtze River received guests, they would take them for a walk along the river and enjoy the view. If a couple were dating, they’d also choose to hang out on the riverbank. So the river was a major form of recreation for people. Another reason we found connection with nature when I grew up was because we didn’t have social media or cellphones yet.

Sixth Tone: What was your earliest impression of the Three Gorges Dam?

Muge: I was very curious about it. I didn’t have any opinions about the dam itself actually. Now I am more concerned about the fact that after it was built, our relationship to (the river) was severed. It caused a break with our way of life of the preceding 30 years, in which the Yangtze River played a major role. Because of the construction of many dikes along the river, you can’t interact intimately with it anymore. You have to observe it from afar.

Sixth Tone: Why did you name the project “Going Home”?

Muge: The earliest pictures in the project were made to document my journey going back to my hometown, and from there on I extended the concept to also include my journey leaving home. “Going home” emphasizes a process, rather than a result of having returned home. The places along my journey underwent a massive change. I hope I will always have the desire to go home, the desire to return to familiar places.

Sixth Tone: Why did you choose to photograph this project in black and white?

Muge: Since the colors of objects can have different looks and feels in different eras, capturing them in color photos would be too realistic, almost too “cruel” as the reality no longer (matches) what I remembered from my childhood. I would rather take a step back from reality and let my photography intervene in a more subjective way. Black-and-white photography is an abstract language that transforms reality and allows me to preserve my beautiful memories as untouched by outside forces.

Sixth Tone: What kind of scenes and people attracted your attention when you were photographing?

Muge: One is a boy on a boat, photographed against the light. Because my hometown is relatively remote, people are not well-off, so they would leave for more affluent cities to look for jobs. There’s a particularly apt term in our local dialect for that, which is “looking for a way to be alive.” Every time we do that, we are dressed our best to show our best sides. That boy’s outfit and expression is just like mine when I made my first trip to Chengdu to attend college. Then there’s one photo of Kai County, the last county seat to be demolished for the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. I followed its demolition from beginning to end. Nothing is left of a nearly 2,000-year-old town, except a yellow hornbeam tree that is a few centuries old.

Sixth Tone: You have worked on this project for 16 years. Have your views on the impact of the Three Gorges Dam changed?

Muge: When the Three Gorges Dam was first initiated, it made a lot of promises, such as that it would improve people’s lives. So when it was built, everyone was quite happy about it, but eventually they lost faith. I have often been asked why the people in my work look so sad, so pained. I think (their expressions) are more of despair resulting from their struggles to come to terms with changes brought on by the torrent of times. Some people who had migrated to other parts of China after their ancestral homes were demolished couldn’t integrate into their new environments. So they sneaked back to the Three Gorges region, only to find nothing left for them.

But now I’m looking at this a lot more rationally. There’s not so much sadness anymore (of losing my past) but a new sense that I need to face whatever happens. No matter if it’s for writers, photographers, or artists making an installation or a video, the bad experiences in our lives cannot be the core of our work. It’s just like after you fall down and hurt yourself, you shouldn’t spend the rest of your life fixating on the pain you suffered. The experience should arouse reflection, so you don’t fall again. So now my work has become a reflection on my home, and perhaps that can be extended to a reflection of people’s ways of life in China under rapid change. It is to figure out how we go from there in terms of development in China. But have I found an answer? No.

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: “Going Home,” 2004-2007. Courtesy of Muge)