To China, With Love: Meeting My Father, Letter by Letter

Editor’s note: Growing up, Huang Zhuocai never got to see his father. From the southern Guangdong province, his father Huang Baoshi spent 50 years as a Chinese immigrant in Cuba starting in 1925. In all that time, he came back to China just once — when his son was born.

But he left in haste two years later amid the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in the late 1930s. He would never return again.

From the minute he could read, however, Huang Zhuocai — now a retired professor of overseas Chinese studies at Jinan University — has tried to piece together his father’s life from the dozens of letters the two exchanged across the ocean over several decades.

In the years that followed and up until his father’s death, Huang Zhuocai never saw him again, but their letters became a bridge. Their correspondence not only tracks the history of China’s fractious relationship with Cuba in the first half of the 20th century but offers rare insight into the private, and often lonely and grueling life of an overseas Chinese citizen at the time.

The letters, which Huang Zhuocai compiled into a book published in 2011 titled “Father & Son: The Memoir of a Chinese in Cuba and the Trajectory of his Family Letters,” led to a unique yet deep father-son relationship — they got to know one another, they looked out for each other, and they were never really alone.

This is their story.

Going from China to Cuba in the 1920s was fraught with enormous challenges and risks. Most traveled by boat — a hazardous journey that took three to four months and cost a considerable sum of money — and not everybody made it to the other shore. A return trip home was considered a luxury.

It was a luxury my father Huang Baoshi and I dreamt of for almost 40 years. That dream ended in 1975 when he died in Cuba, unable to find passage back to China. He’d spent his life struggling to make ends meet but still managed to support his family financially — and emotionally — from almost 14,000 kilometers away.

He always believed he had a way back home, and during his one and only visit back to China, told my mother he’d stay in Cuba for just eight to 10 years to earn some more money and realize his two plans: own a large-scale, modernized poultry farm; and mine the gold in the mountains of our hometown of Taishan, Guangdong province.

Taishan was always famous for being the home to overseas Chinese, especially those who flocked to Cuba. Records show that 45% of the Chinese emigrants to Cuba came from here. My father went to the island nation in 1925, back when it had a robust economy. My maternal grandfather had lived there as an expatriate and returned to China with a bit of wealth. He suggested my father go too, saying, “It’s better than America.”

Born in 1898 into the family of a private schoolteacher, my father had four brothers and two sisters but left home at age 14 to make ends meet. He was an attractive man with charming, dignified looks, who eventually became a traveling salesman of sorts, roaming from village to village to sell his wares. He carried two bamboo baskets with him, which hung off a pole he bore across his shoulders.

But in Cuba, he started off as a barber before being employed by a Spanish family as a servant, after he learned enough Spanish to communicate fluently with locals. He also started building his own nest egg from his earnings and in time opened his own general store, which he ran for decades.

The first large-scale wave of Chinese immigration to Cuba was in 1847. Records show that the government of the Qing dynasty once even sent a chancellor to Cuba to inspect the working conditions of Chinese laborers there. When the Cuban government abolished all work contracts (exploitative agreements offering scant wages and the promise of being released after eight years of labor) in 1870, many were free to work and start businesses there.

Chinese immigration to Cuba only increased after the U.S. passed the Chinese Exclusion Act — an 1882 law that prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the country. At its peak, Cuba housed hundreds of thousands of Chinese immigrants. China’s collapse into warlordism in 1912 after the fall of the Qing dynasty made life difficult for common citizens, so many Guangdong natives moved to Cuba at the behest of their relatives and friends.

My father was among those thousands and went to Cuba in 1925, returning to China just once in 1937 — a year when two momentous events occurred. First, I was born. Having a son left both my middle-aged parents overjoyed. The second was that he built a beautiful, albeit small, two-story house in his hometown, which remains well-kept to this day.

My mother Wu Meiyi often said that having me wasn’t easy. She was already middle-aged when she became pregnant and then couldn’t find a doctor to deliver me when the time came, so my father had to do the job.

He was ecstatic after I was born. Every day, he’d take me to the village outskirts to watch the trains. Our hometown had tracks connecting to Jiangmen, a neighboring city, and we’d watch the trains roar past us with sheer happiness. I was only a few months old and have no real memories of that time, but whenever people tell me about the short time my father and I spent together, they would always say, “Those few months were the happiest days of your life.”

Father, From Afar

Those days lasted but two years. In 1939, my father left for Cuba again when the Second Sino-Japanese war began and Japanese planes dotted the airspace above their hometown of Taishan.

Poor transportation and the lack of phones back then meant that my mother and I, still in Guangdong, could only rely on letters to communicate with my father, who was now worlds away. My father was very much a family man. He wrote often and asked about things back home. My mother would write back when I was still young, but I took over the task once I learned to write. I had over 100 of his letters but have lost many over the years. I now only have about 40 letters.

Of those, the earliest one was written on April 28, 1952:

I received your letter and understand now; please do not worry.

I know you ranked 26th after testing for middle school in the spring and that you’ve started school now. Hearing that makes me unspeakably happy. In my previous letters, I went into detail about knowing a scholar’s place once you start your studies, that pursuing one’s learning and bettering oneself is the essence of the scholar. When it comes to money, you must always be prudent. Plus, your mother is still sick at home, so you should look after her from time to time if you can.

He imparted two lessons that I remember even now. The first was about learning. Under his guidance, I always enjoyed reading and took to my studies diligently. I believe my becoming a professor is irrevocably linked to my father’s guidance. The second was handling and using money. He supported me financially but would also advise me to spend wisely and economically.

Heavily influenced by Western concepts, my father treated me as a friend from a young age, and the tone in our letters was very much like equals. In some letters, he even referred to me with nin, a more respectful way of saying “you” and a word used sparingly by Guangdong locals.

When I was younger, I always thought that he had just written the wrong word, but I realized otherwise years later when we were organizing my father’s letters to publish “Father & Son: The Memoir of a Chinese in Cuba and the Trajectory of his Family Letters” and the editor-in-chief commented, “This nin is a great word. It’s not just an equal father-son relationship; he also sees you as someone worth respecting.”

My father lived in Sagua La Grande (about 300 kilometers from the capital Havana), a wealthier area in central Cuba that also served as its agricultural, industrial, and transportation hub. At its peak, it was home to more than 7,000 overseas Chinese.

In 2014, I traveled there in an attempt to rediscover our roots and found the site where my father’s general store once stood. When local children and adults saw us coming, they swarmed us.

Two elderly people cycling past even stopped at the mention of my father’s Spanish name, Fernando. They said that as children, they’d frequent his shop to buy candy. He treated them kindly, allowing them to take the candy first and pay him later once they had the money.

I asked if he had another family or a girlfriend in Sagua La Grande. Far from home for decades, many overseas Chinese had separate families in Cuba. But they replied, “Your father was very refined. He was the chairman of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (or CCBA, an organization formed to assist Chinese immigrants and liaise with local governments) and wouldn’t behave that way.”

He was chosen for the position in his 30s or 40s and served up until his death. He enjoyed a good reputation and delighted in helping everyone, overseas Chinese and others. If an unemployed person or a local friend asked for help, he’d always take care of them.

During my trip, I also called on the descendants of my father’s adopted son, a man named Idalberto Revuelta Diaz, though everyone called him Tati. He’d lived with my father from a young age and started helping at the store once he grew up. That was until he joined the Cuban Revolution in 1958, for which he eventually gave his life. Cuba later declared him a martyr.

Tati came from a poor but large family, all of whom my father looked after. A relative of Tati’s stopped by to see us during my visit to Cuba and said: “Your father took great care of us and cooked a meal for us every Sunday. He would lend us money when we ran out, and he even bought a gold necklace for me when I was born. I’ll never forget that.”

The Cuban Revolution ended in victory for Fidel Castro in 1959. And at first, the overseas Chinese community thought it was simply another everyday matter, given the regularity of political change in Cuba and South American countries, so they continued with their businesses as usual. But a subsequent series of policy changes made both their businesses and their lives much harder.

Another letter my father wrote explained it all. This one was from April 3, 1959:

I’m not well-off, but I still manage to get two meals a day despite my age (he was 61). If I come home (to China) and end up not having a job for a while, it will be an issue. Did you know that it costs 1,200 Cuban pesos (now $50) to get from Cuba to China? I know many older overseas Chinese people too terrified to act, even with 3,000 pesos in savings, so you can just imagine what it’s like here.

Now, we have a new government in power interested in nationalism, which heavily disfavors outsiders. They’ve also imposed heavier taxes on factories and merchants: Even everyday business has been temporarily frozen. You’re not allowed to sell.

Cuba’s government, newly installed after the revolution, began implementing a policy of nationalization. In his role as CCBA chairman, my father was responsible for working with overseas Chinese people and had assisted the Cuban government, so they treated him well at the time. It wasn’t until 1968, in the last phase of the sweeping nationalization drive, that they seized his store.

He was 70, forced into retirement and given only the equivalent of $2 each month as pension. Life was incredibly difficult. Each month, the state allocated a few pounds of rice, a couple of eggs, a pound of sugar, and a pound of oil for him, but it was clearly insufficient and compelled him to buy other necessities on the black market.

Back in China at that time, I had already married. And life for us had become difficult too amid the Cultural Revolution. My salary had fallen to 20 yuan (now $3) — barely enough for one person to eat — while my wife’s salary of 48.50 yuan had to be split with her own financially strapped family.

Despite his own dire circumstances, my father still managed to send money home, mailing about 100-200 Cuban pesos every year. Cuban pesos had a high exchange rate against the yuan at the time, and his remittance kept our children from going hungry and cold.

All of this made me uneasy, though. I wrote to him, asking if he still had enough money, only for him to reply, “I don’t have much left at all.” By his last letter, which he penned in 1974, he wrote, “I only have about 1,000 Cuban pesos left.” Seeing that broke my heart. How did someone who loved his country, his hometown, and his family so much ultimately suffer such circumstances?

One Revolution Ends, Another Begins

I was only a middle school teacher in my 20s when I was labeled a “reactionary academic authority” during the Cultural Revolution. Things got tough. Some persecuted teachers around me ended up hanging themselves because of such unbearable conditions. Those memories remain bitter and painful for me, even now.

I could only write to my father in secret, or my wife helped out when I was unable. Sensing my difficulties, he wrote back to comfort and encourage me, like in this letter, dated April 25, 1969:

Rest assured that I’ve received your letter from the 25th and the enclosed photo of Yafan (his grandson). He looks quite animated and cute. He seems really happy.

Speaking of your current hardships, don’t be too pessimistic. You and your wife are both talented and smart, so seeking opportunities may help resolve the problems in your life.

You must understand that the cost of living elsewhere is extremely high. Even if you earned a few thousand yuan, you still wouldn’t be able to save anything by the end of the month. I’ve lived abroad for decades now, so I have a deeper understanding of this.

You’re still in China. You can meet your wife and children all the time. What a joy that is! As the saying goes, ‘The home is a place of happiness; beyond that lies a world of misery.’

My thoughts constantly ran amok back then. I thought, what would I do if I couldn’t teach? I knew how to cut hair, so would I become a barber? I knew how to take photos, so maybe I could open a photography studio. I also knew how to repair shoes, so I wouldn’t have to starve to death. I even entertained thoughts of going to Cuba and wrote to my father, “Can I apply for a visa to Cuba on the basis of inheriting a business?” But he ruled that out, saying there was no business for me to inherit.

With all hope lost, I could only bear things out.

By 1970, my father was already in his 70s and chances of him returning to China had grown slimmer, particularly since Chinese-Cuban relations had been souring since 1966.

In a letter dated May 16, 1970, he wrote, “I’m getting old. Whether I can return home remains to be seen.” To console me, though, he signed off nearly every letter, saying: “I feel great right now — no need to worry.”

Despite feeling so powerless during those years of the Cultural Revolution, I still sought out ways through which overseas Chinese could return from Cuba. While I went through formalities and wrangled with paperwork, my father kept busy in Cuba, waiting at the CCBA for a spot to open up before ultimately turning to friends for help.

But nothing came of it. There was just no way for him to come home.

To be honest, he actually did have an opportunity to return. Cuba had nothing beyond sugar to export, which meant that Chinese cargo ships often traveled back from Cuba empty, so the CCBA had arranged for elderly Chinese to take available bunk spaces as a free trip home.

But there were so many people desperate to return home that they had to wait in line. I once met an elderly person who had successfully returned and asked, “Why hasn’t my father come back?” He replied, “He really wants to, but he has such high morals. Every time he gets in line, he ends up giving his spot to someone even more frail, saying he’s in good health and that he can wait.”

In a letter dated March 12, 1974, my father wrote:

My son Zhuocai, I received your last two letters; please do not worry. My response is belated because I’m older. I have less energy, and writing can feel like such a heavy burden…

It’s been nearly six years since I lost my job. It’s hard to make ends meet, and I only have 1,000 to 2,000 Cuban pesos left, which is hard to stretch out over the long term. A few family members (of others) sent U.S. dollars and plane tickets from Hong Kong or the U.S. It really is difficult to get home. It will take at least two to three years before my turn comes around.

If you give your children an education, there’ll be a way out. My health is the same as usual. Please do not worry about me.

He thought his health was fine, but we all knew he suffered from high blood pressure. The scarcity of Cuba’s medical resources also limited his treatment — and ultimately decided his fate.

In 1975, I received the last letter he’d written. Then 76 years old, he wrote he was still overseeing the remittance and repatriation of overseas Chinese. As usual, he had ended the letter by saying, “My health is fine; no need to worry.”

Yet two months later, I received another letter, this time from his good friend, telling me he had died on June 2, 1975 from cerebral hemorrhage. In the end, my father never returned home. And in the end, I never laid eyes on my father again.

He was an ordinary man swept along by the tides of history, living 50 years of his life in a distant country in the Caribbean Sea — up until his wife passed away, up until his son became a man and eventually a father himself.

This article was originally published by StoryFM. It has been translated and edited for length and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editor: Ye Ruolin.

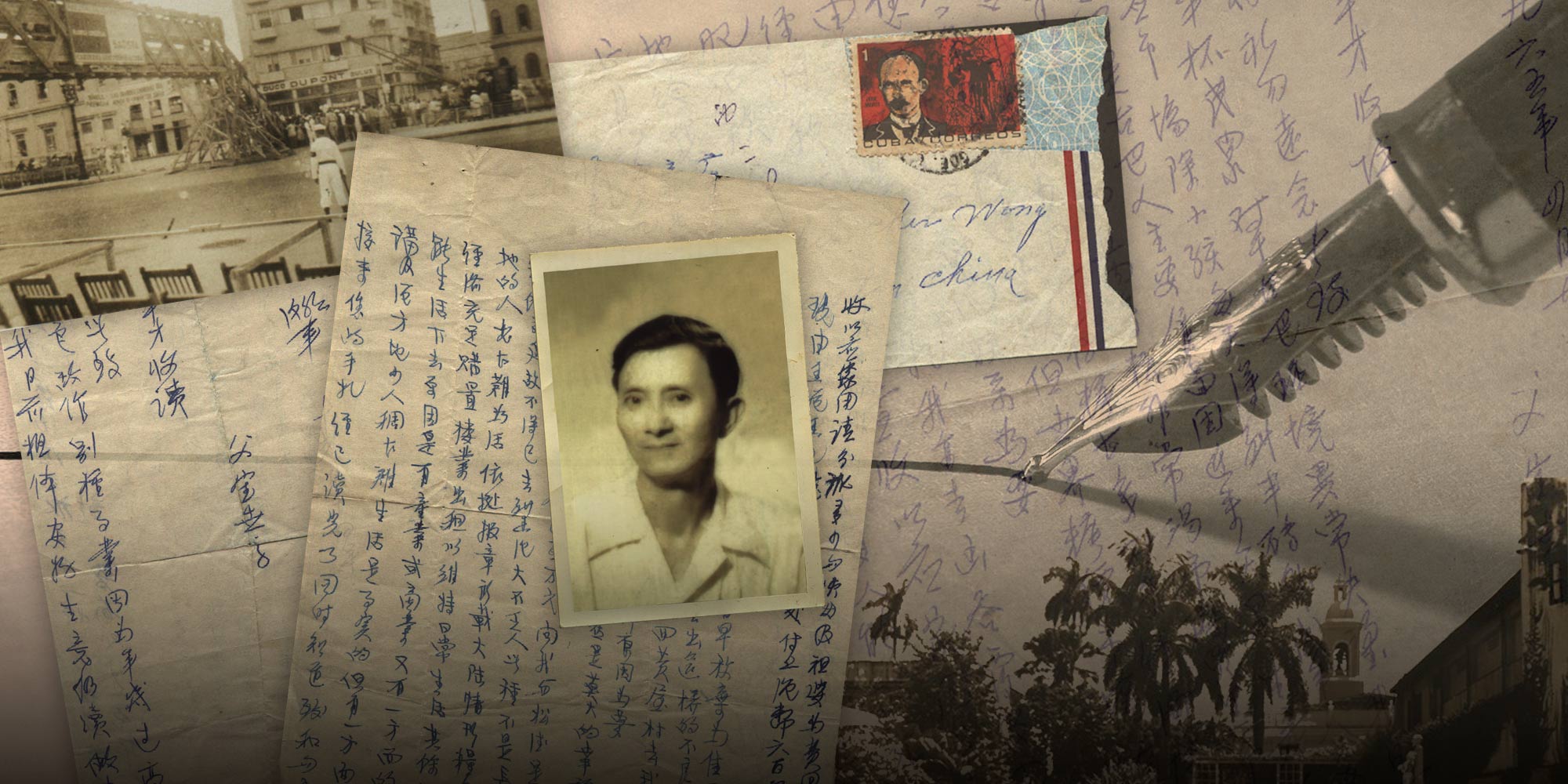

(Header image: Visuals related to Huang Baoshi’s life from Huang Zhuocai and VCG, reedited by Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)