Reading the Leaves of China’s Upscale Milk Tea Craze

On April 2, Chayan Yuese, a viral tea brand based in the central city of Changsha, opened its first pop-up store in Shenzhen. Although Chayan has been a tourist attraction in Changsha for years, the company has been unusually reluctant to extend its footprint outside of central China. The arrival of a location in Shenzhen, even if only temporarily, was met with unreserved enthusiasm among that city’s young, well-to-do residents. At one point, the line to enter the shopping mall where the pop-up store was located grew so long that local traffic cops had to intervene, and shrewd scalpers were able to resell 16 yuan ($2.50) cups of the store’s signature milk tea — a black tea mixed with milk and topped with whipped cream and crushed pecans — for upward of 200 yuan.

China’s tea culture has undergone drastic changes in recent years as companies have rebranded the once-staid beverage as a high-end, fresh, and healthy consumer experience. The resulting products, known colloquially as “new-style teas,” are big business. According to the 2020 New-Style Tea Drink Report, the market for new-style teas grew from 44 billion yuan in 2017 to 102 billion yuan last year. Most of these sales are to young consumers: Chinese born in the 1990s and 2000s account for almost 70% of new-style tea sales, and 27% of them reported spending more than 400 yuan a month on new-style teas.

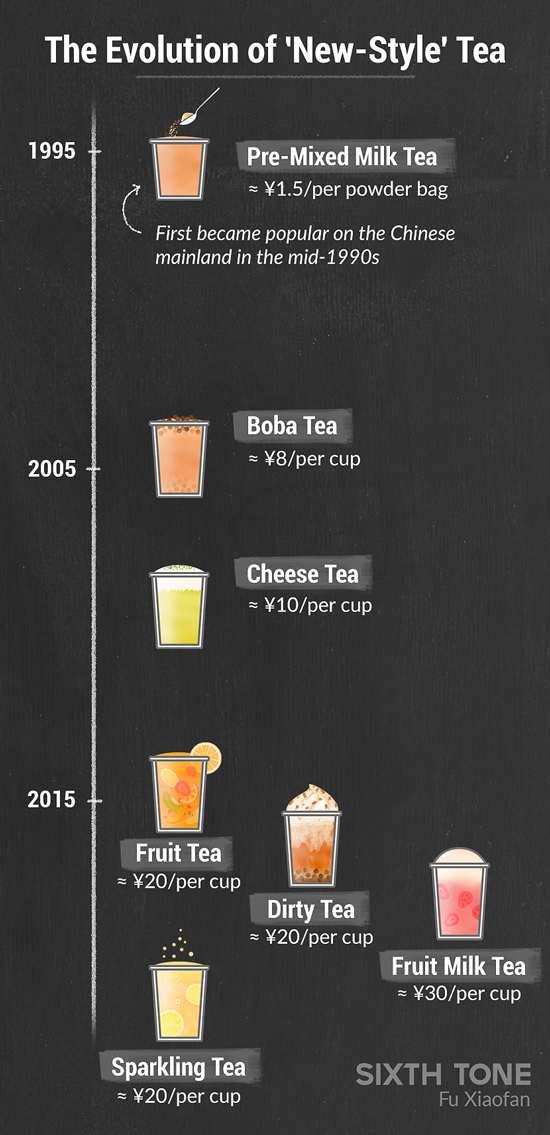

The emergence of new-style teas can be traced back to the cheap roadside milk tea stands of the 1990s. Most of these drinks were made from powdered mixes and contained neither fresh milk nor fresh tea. The base ingredients weren’t updated until the arrival of higher-end Taiwan-based brands like Coco and Alittle Tea in the 2000s, leading to innovations such as “cheese tea.” These franchises ushered in what can be called the “Milk Tea 2.0” era, transforming the milk tea business from a hodgepodge of small stalls into a standardized and fast-moving industry. As of 2017, Coco reportedly had more than 2,000 stores on the Chinese mainland.

But even as the Taiwan-centric “Milk Tea 2.0” revolution was sweeping the world, the seeds of its next evolution were already sprouting on the Chinese mainland. In 2012, a 21-year-old named Nie Yunchen opened a milk tea store in the small southern city of Jiangmen, where he sold milk teas topped with a salty layer of cream cheese. By 2020, Nie’s HeyTea had 695 stores worldwide, was worth an estimated 16 billion yuan, and had spawned a raft of imitators.

The new brands made their mark by offering a more diverse range of tea bases, often with extras like seasonal fruit, sparkling water, cream cheese, or nuts. These extras don’t come cheap, and the explosive growth of new-style tea brands like HeyTea has split China’s tea market into at least two tiers. The pioneers of the second wave, such as Coco and Alittle Tea, have largely kept prices below 20 yuan, even on new-style teas, while HeyTea and rival Nayuki have aimed for a more upscale market, selling teas and other beverages for between 20-30 yuan, or roughly the price of a Starbucks latte.

The viability of this business model owes much to China’s widespread, though still uneven, embrace of high-end consumerism. Jason Yu, general manager of the market research firm Kantar Worldpanel China, told me that “mothers with refined tastes,” urban white-collar workers, and those born after 1990 are the main drivers of China’s new-style tea market — and, more broadly, the consumer market as a whole. These groups tend to be defined by busy work and home lives, and they see upscale beverages like tea and coffee not only as a way to quench their thirst, but also as a source of comfort. In this sense, new-style teas are filling a psychological, rather than a physical need.

Many tea brands are aware of this, and they have sought to associate themselves with a healthy and relaxed lifestyle through their marketing campaigns. HeyTea, for example, embraced the country’s pastoralism fad in a recent ad campaign, which sees one of the company’s fruit teas transport a young woman from the stresses of work into a beautiful rural wonderland.

Another driver of new-style tea consumption, according to Yu, is the desire among young urban Chinese to merge consumption and social activity. “The goal of consumption for this generation of consumers is socializing,” Yu said. “You rarely see a person drinking HeyTea by themselves.”

In this sense, the rise of “Milk Tea 3.0” is following in the footsteps of coffee’s second wave, which saw brands like Starbucks turning cafés into hangouts. Many new tea shops are no longer simply holes in the wall where you buy your drink and leave: They have built-in dining areas with bright and sleek interior designs, floor-to-ceiling windows, and other features that make them look appealing on social media. China’s ubiquitous food-delivery apps have also made tea drinks a part of office culture, as group ordering a round of afternoon milk tea has become something of a ritual for sleepy office workers.

But the real power behind new-style tea’s takeover of the Chinese market is all the capital sloshing about the industry. Tea is a business with a low technical barrier to entry. Although some brands have sought to patent their star products, it remains relatively simple for other companies to make slight modifications to the recipe and produce popular derivations of their own. Given the fierce competition and prevalence of copycats — Chayan Yuese just triumphed in a lawsuit over a company that had named itself Chayan Guanse — success is dependent on a company’s ability to achieve scale and brand awareness, both of which require money. This January, a lower-end new-style tea brand with 12,000 stores, Mixue, successfully solicited 2 billion yuan in investment, raising its estimated value to 20 billion yuan. In February, Nayuki submitted a prospectus to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in advance of a likely initial public offering. Industry insiders say it is only a matter of time before HeyTea, which nearly doubled its total number of storefronts last year alone, does the same.

This, too, is reminiscent of coffee’s Starbucks-led second wave. But where does that leave smaller, locally oriented brands like Chayan? The company’s founder, Lü Liang, has so far opted out of the current expansion craze, likening it to a fever. Still, he understands the motivation. “I thought the fever would break after a year, but it just keeps burning,” Lü told an industry publication in 2019. “It can feel like there’s no choice. Markets don’t let you stand still. … Even if you know you have a lot of problems, you just have to charge forward.”

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: HeyTea employees inspect drinks at a branch in Qingdao, Shandong province, 2019. People Visual)