China’s Newly Released Census Data in Four Charts

Following months of intense speculation, China has released the data from its seventh census conducted last year, shedding light on demographic trends that could shape the country’s future.

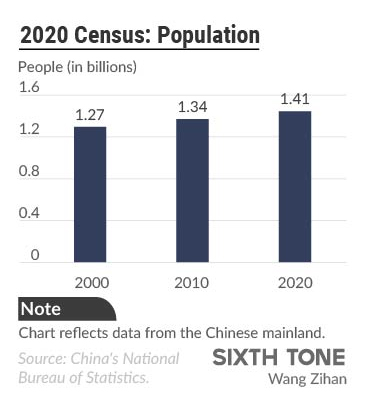

At a press conference Tuesday morning, authorities revealed that the Chinese mainland’s population in 2020 was 1.41 billion, an increase of 5.38% compared with the 2010 census. Meanwhile, the average annual growth rate over the past decade was between 5% and 6%, consistent with the 2000-2010 rate.

Ning Jizhe, commissioner of the National Bureau of Statistics, suggested that many factors are contributing to China’s relatively slow population growth, including fewer women of childbearing age, couples opting to delay having children, and the higher cost of raising kids.

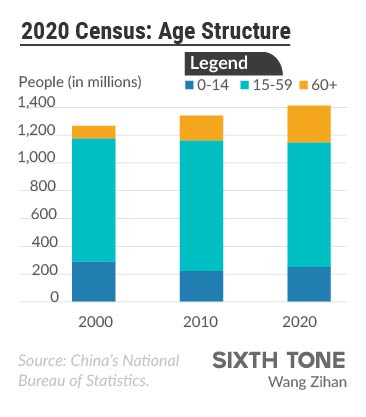

As a result, the country’s elderly population has risen precipitously, with the 2020 census recording almost 50% more people aged 60 or above compared with 10 years prior. There are also slightly more children aged 14 or below, likely due to the one-child policy being relaxed in 2016. Together, these higher proportions of very old and very young people are a greater strain on the country’s social security system.

Ning added, however, that people aged 60 to 69 — many of whom are still healthy enough to contribute to society — account for more than half of all elderly.

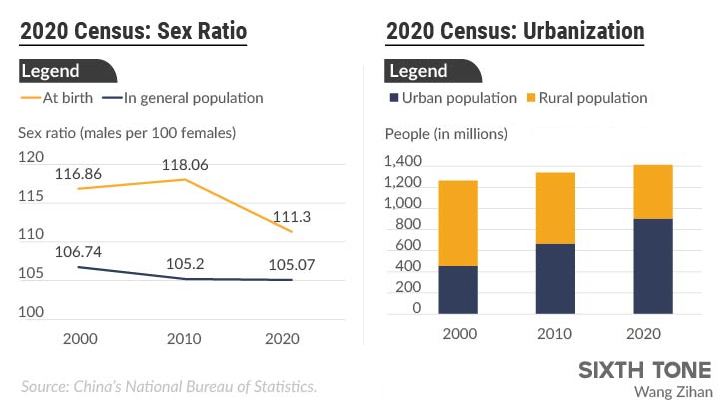

China’s sex ratio at birth was 111.3 in 2020, meaning 111.3 boys were born for every 100 girls. While high, this figure represents a decrease from 118.1 in 2010. According to UNICEF, the natural range for sex ratio at birth is between 103 and 107.

Another notable trend is urbanization. For the first time, China’s urban population outnumbered its rural population, indicating continued migration to more economically developed areas, such as the country’s eastern and southern coastal provinces.

This rise may be attributed in part to a larger recorded “floating population” of migrant workers — people born in towns and villages who later move to urban centers for work, living there most of the year. This group of some 376 million people was nearly 70% greater than in 2010.

Chang Qingsong, a demographer and associate professor at Xiamen University, said the historically high urban-to-rural ratio is a reflection of China’s success in urbanizing large swaths of the country. But there is still work to be done, he added, particularly with respect to providing assistance to migrants, who can’t access social services in cities because of rigid local residency rules.

“The government should not let household registration remain an impediment that keeps the floating population from enjoying local social services,” Chang said. “The relevant departments should hasten reforms of the household registration system in order to achieve ‘complete citizenship’ for this group.”

This article was updated to include an interview with Chang Qingsong.

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: A woman pushes an elderly man in a wheelchair as a mother looks after her children nearby, Beijing, May 10, 2021. Andy Wong/People Visual)