Lancet Report on 70 Years of Chinese Health Highlights Progress, New Challenges

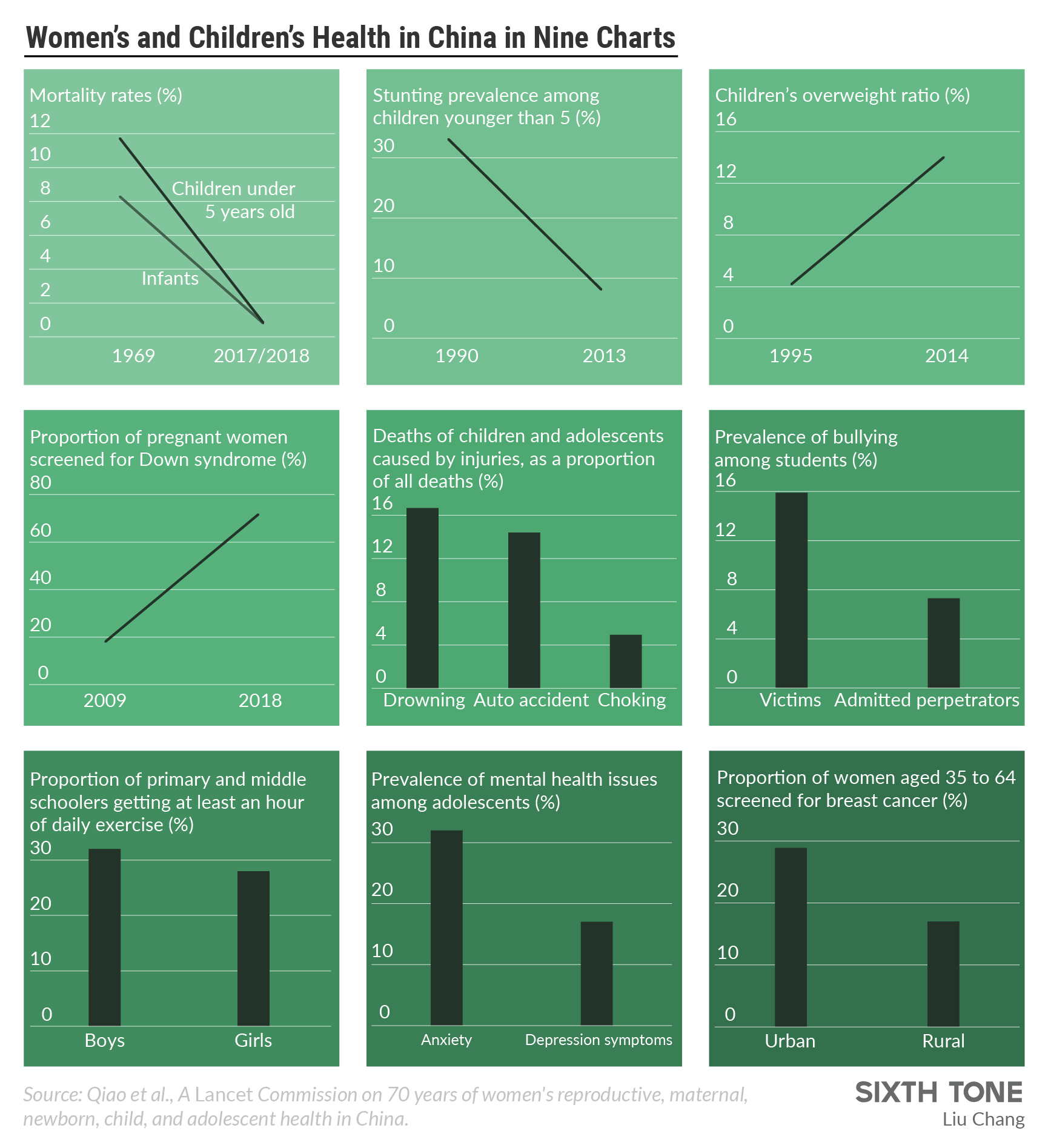

With improved resources and targeted policies, China has seen dramatic improvements in the health conditions of women and children over the past 70 years, resulting in a significant reduction in mortality and disease.

In a paper published Monday in the medical journal The Lancet, a team of doctors reviewed the development of women’s reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCAH) in China since the country was founded in 1949.

“I’m really proud of China’s current RMNCAH system,” Jiang Fan, a coauthor of the paper and a pediatrician at Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s School of Medicine, told Sixth Tone. “With such an enormous population and land mass, making sure health policies are effectively implemented to reach individuals living in the remotest villages — which is what we see from the data — is truly a triumph.”

The review also pointed out, however, that while China has succeeded in boosting maternal and child survival rates, some challenges in maintaining the well-being of individuals remain.

Here’s our run-down of key takeaways from the paper:

Lower mortality rates

The country’s maternal mortality rate, tracking women’s deaths between pregnancy and 42 days after childbirth or termination, has dropped from 15 deaths per 1,000 births in 1949 to 0.178 deaths in 2019, a rate comparable to that of high-income countries, according to the World Health Organization.

The infant death rate in China — once as high as 200 per 1,000 births in 1949 — has decreased to just 5.6 deaths per 1,000 births. Moreover, the infant mortality gap between children born in urban versus rural areas has shrunk significantly.

According to the report, physical injuries such as drowning, traffic accidents, and choking are claiming more young lives than any other risk factor, accounting for 45% of all deaths among those aged under 19.

Jiang said China has seen a major shift in the causes of children’s deaths in the past few decades. “Malnutrition and infections such as pneumonia used to be the leading causes of death for children,” she said. For example, the proportion of children who were underweight decreased from 19% in 1990 to just 2% in 2013. As China’s economy has grown, environmental hygiene has improved, and vaccines have become widely available, the impact of disease has dropped below that of injuries from accidents.

“Our pattern is becoming more similar to what’s seen in developed countries, although we still see some inequality,” such as children living in poorer regions running a higher risk of dying from infections, Jiang said.

While Chinese laws cover some injury prevention measures recommended by the WHO, such as setting a minimum drinking age and making bicycle helmets compulsory, the paper’s authors said the effectiveness of these policies is limited because not all regulations have specific government offices that are tasked with enforcing them.

“The risk of injury for millions of children can be reduced by ensuring that effective interventions are covered by national laws with accountability lying with specific governmental departments,” the authors wrote.

Cancer screenings lagging

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer among Chinese women, accounting for nearly 20% of all cancer cases in the country and affecting tens of thousands of women.

Since the late 2000s, China has provided free breast and cervical cancer screening services to the country’s 300 million women aged 35 to 64, with screening facilities reaching hundreds of the poorest counties. But national data suggests that only 22.5% of women in this age group had undergone breast cancer exams, and only 26.7% had been screened for cervical cancer.

In addition, China’s uptake of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, which can reduce the risk of cervical cancer, has remained low. The inoculation rate for girls aged 9 to 14 is less than 1%. The authors wrote that the vaccines’ short supply and high price tag, as well as low awareness among women and parents, are the main reasons women aren’t getting vaccinated.

The authors cited a 2012 paper published in the Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention pointing out that only 24% of Chinese women of childbearing age and 25% of parents of adolescents had heard of HPV vaccines.

Improved prenatal care

Since 2010, China’s central health authorities have been giving out free folic acid supplements to women planning to become pregnant in order to lower the risk of fetal birth defects.

More fetuses and infants are getting tested for birth defects including Down syndrome, hearing impairment, and inherited metabolic disorders. The screening rate for Down syndrome, for example, rose from 18% of all pregnancies in the country in 2009 to 72% in 2018.

Hearing impairment screening for newborns also increased from about 30% in 2008 to 87% in 2016. While overall improvement has been achieved, disparities between different socioeconomic groups persist, with high-income, well-educated families being favored, the authors wrote.

Domestic violence and women’s mental health

The paper reported that 17% of women in China suffer from perinatal depression, a condition that occurs during or after pregnancy. For comparison, according to a previous study, between 7% and 15% of women in high-income countries experience depression before childbirth, and around one in 10 experiences postpartum depression.

In 2011, China’s top health authority recommended incorporating mental health checkups into care for pregnant women, but psychological services remain limited, the authors wrote. Mental conditions are also highly stigmatized in China, which limits access to these services.

As many as 78% of all women are victims of psychological abuse at some point in their lives, the paper said, citing a 2018 survey conducted across six Chinese provinces. Meanwhile, physical and sexual violence may be perpetrated against 40% and 11% of women, respectively. Over half of Chinese women could experience two or three types of violence in their lifetime.

“Intimate partner violence in particular is still deemed a private matter, and a source of shame and guilt. Therefore, more research is needed into the causes and consequences of sexual and gender-based violence in women to develop more effective interventions and policies,” they wrote.

The authors recommended that primary care facilities as well as obstetrics and gynecology departments conduct routine screenings and provide counseling services to root out violence against women.

Child and adolescent health

In recent years, Chinese people including children are shifting toward more sedentary lifestyles and spending longer hours in front of screens. As a result, the myopia rate among children aged 7 to 18 increased from 47% in 2005 to 57% in 2014. In addition, children aren’t getting enough exercise, with only 32% of boys and 28% of girls meeting the central government’s recommendation of at least one hour of daily physical activity.

“The lack of physical activity isn’t just about obesity — it can also impact mental health,” Jiang said. “These lifestyle changes in recent years, plus other factors like stress, have worsened the mental health status of our children.”

According to the report, 17% of adolescents have shown depression symptoms and 32% have anxiety or anxious tendencies. “While mental health conditions don’t kill so many children, they place a high disease burden on society,” Jiang said.

Meanwhile, children continue to face physical, mental, and sexual abuse. The authors cited research from 2015 suggesting that 27% of Chinese children had been physically abused, 26% neglected, and 9% sexually abused. More recently, a nonprofit group’s 2020 report found that one-third of all child sexual abuse in the country happens at schools.

“But honestly, we don’t have good data to reflect the scale of child abuse and neglect,” Jiang said. She’s concerned about the “lack of experts and pediatricians who are trained in the field of child mental health,” and said training child psychiatrists and clinical psychologists should be a top priority.

But overall, Jiang sees real, radical improvements in China over the past 70 years. “We’ve come a long way in ensuring basic survival for women and children,” she said. “Now we are aiming for prosperity and a higher quality of life.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image and icons: People Visual)