A Gaokao Expert Speaks: Scores Don’t Mean Security, Money Does

In 2015, Liu Jiasen was living the dream. He was Hengshui High School’s top humanities student, or “No. 1 Scholar,” in that year’s gaokao — China’s grueling college-entrance exam — and he’d just been accepted into the department of Chinese language and literature at the prestigious Peking University.

He remembers thinking at the time how he’d become an alum of the same institute home to China’s leaders. So much so that after the gaokao, when most students rushed to learn how to drive, Liu didn’t. He thought instead that since he wanted to “contribute to society,” the state would “give me a driver.”

He wasn’t prepared for what came next.

At university, Liu says, one of the first things drilled into most students was that “the Chinese department does not train writers,” and that “accepting one’s own mediocrity” had long been the culture there. That, and the course was mostly about Classical Chinese and the history of literature — not the creative writing Liu had expected.

Despite being a student in the best Chinese department in the country, he realized there wasn’t much of a career to build after graduation. Liu once approached his class counselor asking if he’d ever make a million-yuan annual salary after graduation. “No,” came the blunt reply, leaving Liu bitterly disappointed but determined to prove otherwise.

Then opportunity knocked. In his freshman year, a veteran high school teacher who’d quit his job to publish teaching aid books contacted Liu to purchase his high school notes. These notes were valuable. After all, he was a former top scorer at Hengshui High School in the northern Hebei province, a cram school renowned for producing “exam experts from small towns,” or students from rural China who crack the gaokao against all odds.

One year later, the same teacher, who now owns a company called Chinese Culture Ltd., wanted him to give speeches based on his experiences at Hengshui High School — as an exam expert. He offered tens of thousands of yuan “to cover tuition and living expenses.” Liu agreed immediately.

So for the next few years at university, Liu led two lives: He was a student for four days a week in college; the other three days he went back to being the “No. 1 Scholar” giving talks at high schools across the country to students eager to emulate his feat.

That’s his job now — reliving the story of his crowning glory at Hengshui High School. It’s given him everything he wanted, but what his degree couldn’t promise: fame, a career, and — most importantly — money. He’s been with the company for nearly five years now and has over 600 speaking engagements under his belt.

Liu is only 24 years old and has already earned close to 2 million yuan ($310,000), but says he still has a long way to go.

Inside the exam factory

Liu is preparing to embark on his next lecture tour, likely to last nearly a month as he travels to several schools. After hundreds of such speeches, Liu says he’s often in a daze about his whereabouts. Each speech blurs into the next: hundreds of faceless high school students wearing similar uniforms; school campuses indistinguishable from the other; and principals spouting the same rhetoric.

And in the Q&A sessions that follow his speeches, students always ask the same questions: “How should I study Chinese? How should I study math? How should I study English?”

At most venues, he stands in front of an enormous red sign that firmly underscores his credentials: “Liu Jiasen, Hengshui High School No. 1 Scholar and Peking University Talent: Massive Speaking Tour,” and “Believe in the Power of Role Models.” He usually opens with the same line: “I am not from Hengshui, but from Zhuozhou, a small city in Hebei.”

As he speaks, there’s mostly silence offstage, which is also something he is familiar with. Monotony, repetition, silence — it’s exactly the same as Hengshui High School.

In recent years, the school has earned a reputation for its almost military-style teaching methods and has even opened branches in other provinces. It is designed with just one purpose: to prepare high school students for the gaokao.

Liu recalls studying more than 100,000 practice questions. Each morning students would shout “struggle for the country, struggle for the people, struggle for myself — I can do it, I will do it!” to pump themselves up.

As one of the best products of Hengshui High School, Liu was always good at exams. He once believed Hengshui High School was a burden: He didn’t know then it would eventually become his boon. But he still doesn’t consider himself among the “exam experts from small towns” in the strictest sense — he comes from a double-income family and his father is a civil servant.

According to his observations, only certain families from small cities — such as the self-employed, civil servants, or children from double-income families — have the opportunity to attend Hengshui High School.

He was admitted after getting good results in the high school entrance exam and after a comprehensive assessment of his junior high school grades ranked him fourth in his hometown of Zhuozhou, in the northern Hebei province.

Looking back, he recalls that students at Hengshui High School squeezed what little time they had outside school to study. Every third Saturday, students could take half a day off, leave school, and return the next morning. On such occasions, Liu’s parents stayed with him in Hengshui at a local hotel for the night.

But even then, he still chose to study overnight, because at school, teachers would inspect dormitories after lights-out to prevent students from studying in secret. Liu says he also tried to save time by not changing his clothes for 21 days, until he developed nail infections and had to stop.

Liu also spent time allotted for showering and doing laundry to instead solve 40 small homework problems and eight large ones — such anecdotes are now inspirational stories in his speeches.

When asked if Hengshui High School is not just a school but also a business, Liu agrees. Students invest their time to produce grades, he says, and this in turn becomes the performance appraisal criteria for teachers. He adds that it wasn’t uncommon for a teacher to tell students outright: “If you get good grades, I can get a new car.”

According to Liu, it made teacher-student camaraderie difficult. One teacher even deleted all the students’ social media WeChat accounts after graduation, so the messages they sent wouldn’t “affect his work.”

But Liu says he “understood” that this was the job of teachers at Hengshui High School. And that in this “workshop,” as Liu puts it, students and teachers were trapped together.

One school, two systems

At Hengshui High School, Liu says, motivational signs were everywhere: “I stand proudly on top of the nine heavens, and wish to remain king forever,” “Raise the score one point, leave 1,000 people behind,” and so on. In group talks, students often heard the cliche, “If you work hard, you can change the world.”

Compared with these grand narratives, Liu says the values teachers gave students were more pragmatic. In his senior year, Liu’s homeroom teacher called him to his office for a private chat and told him: “If you want to be rich, you need more knowledge.”

According to Liu, most students at the school had yet to experience society, and because of the closed environment of the schools, their ideas were primarily instilled by others. In that isolated world, Liu says, students are faced with a “split” between two value systems — rhetoric versus real-world pragmatism.

Under the influence of this dual-value system, Liu says he witnessed a sense of “absurdity.” In his sophomore year in college, he came up with the premise for a novel. It would be a story set in a country where nobody speaks and everybody moves slowly. In it, the people are divided into several categories — akin to Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel “Brave New World” — each with its own color, with the people’s only activity outside of sleeping counting beans. The one who counts the most gets the prize. At the end of the story, everyone goes mad.

Liu expects to finish and publish the novel soon, hoping it will “draw society’s attention” and “promote the reform of Hengshui High School, or even make it disappear altogether.”

But back in his three years of high school, Liu quickly rose through the ranks. He went from the 586th place in his first monthly exam to the top — the comeback story he mentions in every single speech. As a top student, he advanced level by level, all the way to becoming the “king.” At the time, he felt he’d become “a person who’d change history.”

But that was only until he set foot in the world outside Hengshui High School.

After the gaokao, his parents took him out to buy a cellphone. In high school, Liu had no contact with computers or the internet, and he’d imagined cellphones had larger keyboards. Recalling a large-screen smartphone he saw on the counter, he felt “like it was a lifetime ago.”

When filling out college application forms, Liu did not choose economics and management, like other top students. He decided to join the Chinese department instead, thinking little about “the pursuit of money,” confident that he “had a good imagination about literature.”

At the university’s student orientation, he introduced himself with: “My name is Liu Jiasen and I am the No. 1 Scholar of Hengshui High School in the humanities.” After a moment of silence in the classroom, one student started clapping, followed by a reticent applause.

The response wasn’t as enthusiastic as he’d expected. After several similar orientation sessions, Liu just stopped mentioning the term “No. 1 Scholar.” He realized that the cheers were just to save him some embarrassment.

And seeing students immersed in the Peking University library’s antiquated reading room, Liu recalls being confused, and a little envious. He didn’t understand the point of devoting one’s life to studying an academic problem, particularly one that seemed trivial to outsiders. He says he wished to understand such people, and how they could feel stability and happiness knowing there was no fame or profit in doing so.

“I panicked,” he says.

Money, money, money

That panic has slowly ebbed over the years as his speaking career has taken flight, but Liu is still anxious about money.

He says he’s been sensitive about material life since he was a child. He remembers when he moved to Zhuozhou City when he was a 3-year-old — the house was around 120 square meters, but the only decent furniture was a tube TV and a set of EZ chairs sent by relatives. The white paint on the ceiling and walls made him feel like he was “living in an empty home.”

In that small town, eating at KFC was considered a big deal. Until he graduated from high school, he was convinced that if “you don’t study hard, you won’t have anything to eat.”

He first became aware of class differences in junior high school. Some of the students from wealthier families in his class stuck with Liu because of his good grades. In Hebei, Liu says, where academic competition is fierce, having an “educated” friend is the “dignified” thing to do. So Liu and more affluent children mixed together, and his dinners and karaoke sessions didn’t cost him his own money.

But as a consequence, his ranking slipped from among the top 100 in his grade to below 800. When he saw the ranking, Liu was stunned. He recalls thinking, “No matter how much they play around, their families will prop them up. But I have no one to prop me up.” He needed to work hard to climb back. The higher he could climb, the safer he’d be.

Something more visceral occurred at college. At that time, Zhihu — China’s Q&A platform — was becoming popular among the student community, and discussing social issues became Liu’s main source of exposure to the real world.

He often followed the news about housing prices. Once, when he checked the price of houses near Peking University, he learned that 1 square meter in a Beijing neighborhood built in the 1990s could be sold for 100,000 yuan. His hometown of Zhuozhou was just around 20 minutes away from Beijing by high-speed rail, but the price of houses in China’s capital was 10 times greater than the price in Zhuozhou.

That’s when Liu jumped at the speaking opportunity offered by his former teacher and Chinese Culture Ltd. His first speech was in the summer of 2016 at a high school in Shangrao, the eastern Jiangxi province. For that, he prepared for a month, wrote 20,000 words, and rehearsed at home every day, practicing various gestures and his intonation.

But at the podium he was still anxious. The principal had called upon the entire sophomore class and they filled the auditorium. His speech was long and he didn’t look up once, reading his script word for word. After the first session, the principal said he spoke well, and arranged two more sessions for the other two grades.

At the end of the three speeches, Liu’s mouth was dry but he was happy: “I didn’t know this could be so popular,” he recalls thinking, and that such speeches could be so “marketable.”

That’s how Liu Jiasen of Hengshui High School began his lecture tour career. Every week, according to the company’s arrangements, he travels across the country to high schools where he addresses students, and in each speech, he always mentions the teaching aid books produced and sold by the company.

Despite the success, one year’s income was still not was not enough to buy even 1 square meter of property around his school, but compared with other students, Liu felt he was doing better.

Boss Liu

Once while still at college, he recalls, he went to the mall and spent 3,000 yuan on a coat. He put it on and walked out of his dormitory. All the while he tried to hide his inner pride with a serious expression.

Now, on most days, Liu wears the same plaid shirts he did in junior high school. But, when he first started his lecture tours, he says his appetite for material possessions increased exponentially. At the time, he’d buy 10 outfits online in one breath, and put the ones that didn’t fit in a closet, too lazy to return them.

He also followed style tips for men online to match formal clothes for himself. He dressed carefully, permed his hair, and went about confidently. “With that flashy look, I looked like a businessman from the 1980s,” he says.

During his sophomore and junior years, Liu Jiasen was squeezing time and stretching his efficiency to the fullest — just like at Hengshui High School. At his busiest, he had to speak four days a week at eight different schools. During this time, Liu says he changed.

When he graduated from high school, he “couldn't speak well,” he says, but now his voice booms, and he can speak for four or five minutes without stopping. He’d treated his roommates to dinner and bought them so many gifts that his friends in the dorm jokingly called him “Boss Liu.” He prefers this to “No. 1 Scholar Liu.”

His thoughts soon turned to taking the leap to make his first 1 million yuan. A year into his contract, he took the initiative to ask the company to link his salary to book sales. After nearly five years with the same company, Liu says he has earned nearly 2 million yuan.

But as his next lecture tour approaches, Liu is conflicted about the students he’ll address. He often wonders if he should tear the veil off their illusions and help them accept the truth of this world.

The most he can do, and the most pragmatic, is to remind students that “exam experts from small towns” are not necessarily suitable for foundational disciplines — they might end up disillusioned or worse, unemployed.

“A core dilemma for them is that they have not yet experienced life, but they are responsible for their lives –– yet they can only learn what life might be like in the future through the words of others,” he says.

A version of this article was originally published by NOW. It has been translated and edited for length and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Lu Hua and Apurva.

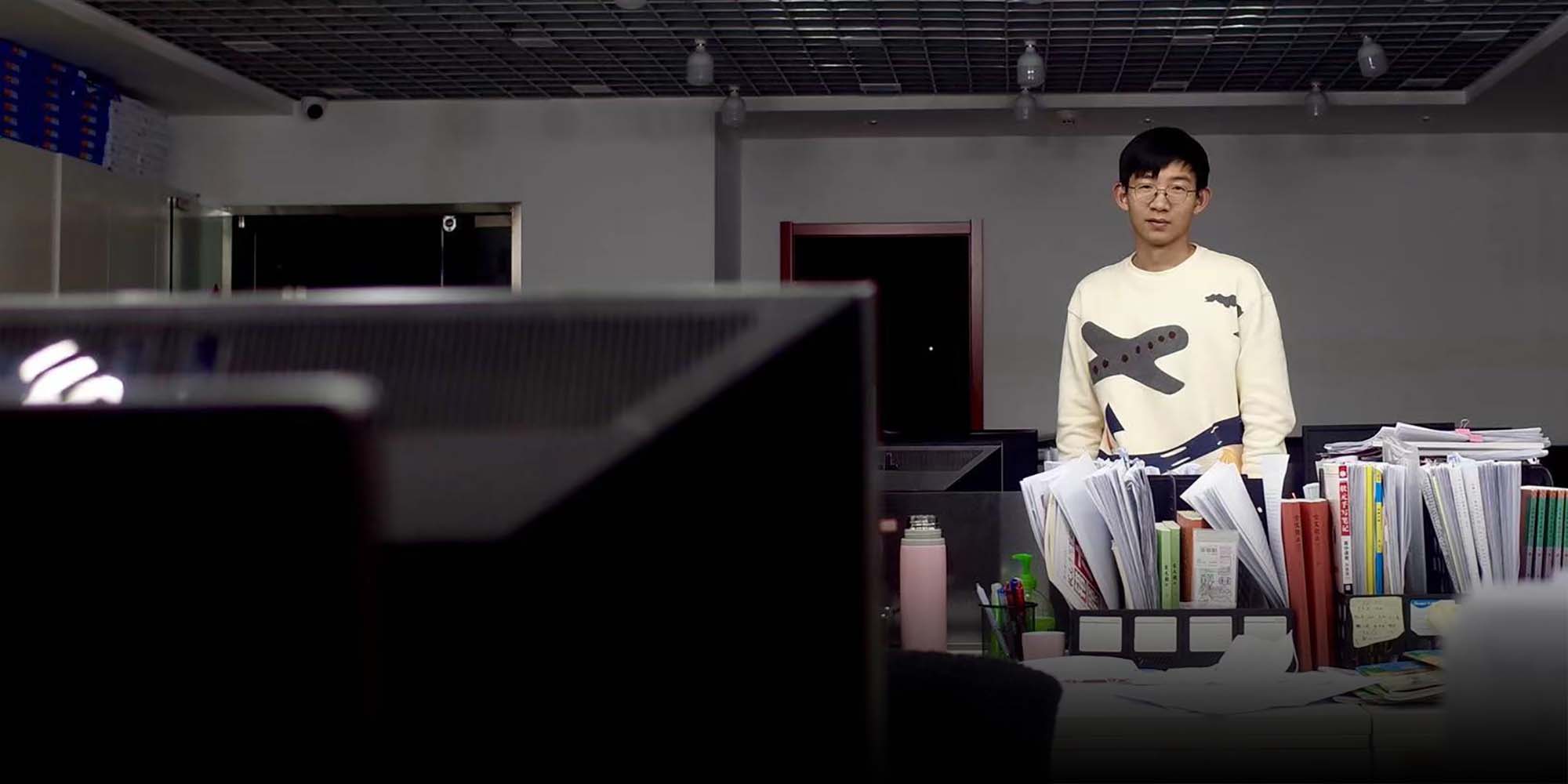

(Header image: Liu Jiasen poses for a photo at his office. Li Yiming for Sixth Tone)