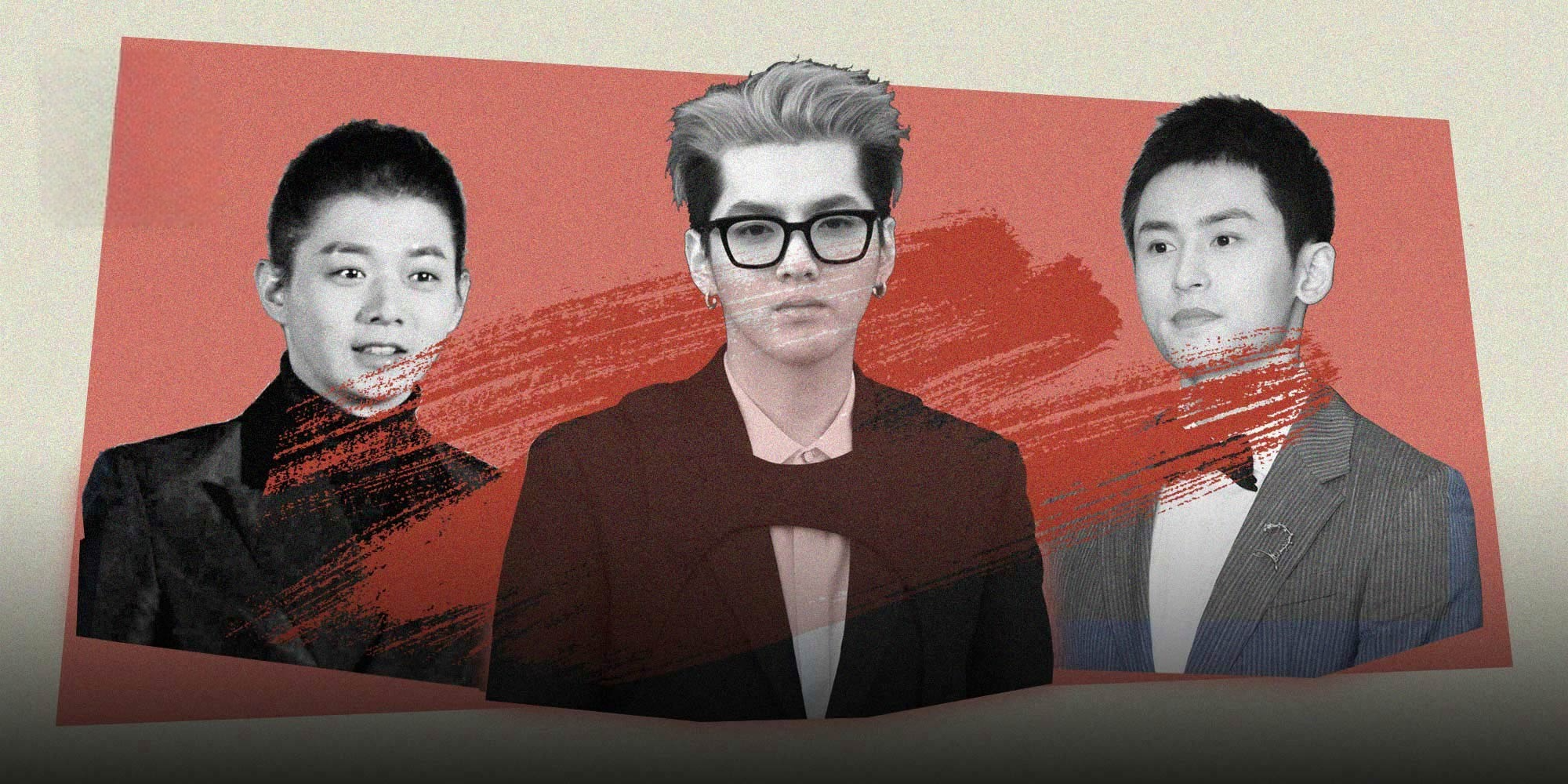

What Does the Future Hold for China’s ‘Little Fresh Meat’ Idols?

As a former Kris Wu fan, 26-year-old Chen turned to brands endorsed by the Chinese-Canadian pop idol without any questions. But not anymore.

The starstruck follower severed her eight-year loyalty after Wu was accused of raping a woman, leading to his arrest Monday. In the days since the accusation surfaced, several domestic and international brands have ended their partnerships with the star, while online platforms have deleted shows featuring Wu.

“I was suspicious about previous accusations against Kris Wu, but I believed the details in the accusations this time,” Chen told Sixth Tone using a pseudonym, fearing retribution from his remaining fans.

Over the past decade, brands have used male celebrities such as Wu, and others like singer Lu Han, actor Wang Yibo, and actor Liu Haoran, to woo women consumers. Their porcelain-looking skin and well-groomed looks earned them the moniker “little fresh meat,” and both businesses and celebrities capitalized on the trend to entice women and men to buy everything from clothes, jewelry, makeup, tissues, beverages, and even fried chicken.

While the trend of consumers falling for flashy images hasn’t necessarily changed, industry experts say spending habits are increasingly influenced by their opinions. Wu’s case in particular not only concerns the issue of celebrities behaving badly but also holding them accountable when they do.

“Conversations about sexual misconduct have always been there, but it used to be swept under the rug,” Miro Li, the founder of Shenzhen-based branding and marketing consultancy Double V, told Sixth Tone. “Now, with more and more incidents such as comedian Yang Li’s controversial gender-related quips, and the alleged rape case at Alibaba, people have realized they need to voice their discontent.”

Stars being called out on social media for their actions have often culminated in boycott campaigns. While some have been canceled over grave issues, including sexual harassment and rape, others have fallen because of moral and ideological differences.

Last week, singer Huo Zun was grilled over his perceived lack of morality by social media users after his former partner accused him of cheating. He responded by saying he was ending his singing career.

Actor Zhang Zhehan was also shunned last week after photos of him posing at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, a site honoring Japanese war criminals, surfaced online. While many fans slammed him for “dishonoring China’s history” and its invasion by Japan, more than two dozen brands — including French luxury fashion brand Lanvin and Japanese jeweler Tasaki — immediately canceled contracts with the actor due to his tainted public image.

“The Yasukuni Shrine is a spiritual tool and symbol of Japanese militarism for inciting wars against other countries, and a place for Japan’s right-wing forces to deny history and glorify invasions,” the Chinese Association of Performing Arts said in a statement. “For performing arts professionals, establishing the right point of view toward history is basic ethics.”

Li, the marketing and branding expert, said while celebrities in other countries may have been wary just about their ethical boundaries, those in China also need to tread carefully when it comes to issues ranging from history to public opinions.

“In the West, there might be issues in race and ethnicity or about LGBTQ community,” she said. “In China, Zhang’s case showed that one also needs to be aware of ideological issues.”

In China, domestic and international brands with large consumer bases are increasingly cautious over any faux pas that may be deemed offensive to avoid business risk. The “fan economy” is a factor that companies just can’t ignore or neglect, experts say.

“In addition to basic factors such as idols’ social traffic and their compatibility with the brand culture, brands also look at their fans’ stickiness and whether there is a ‘fan head’ to improve engagement between fans and brands,” Shane Xin, a Shanghai-based public relations executive, told Sixth Tone.

Chen, the once-loyal fan of pop idol Wu, said that the so-called fan heads have similar roles to a company executive, strategizing everything from finances to promoting their beloved stars. The fan circles — known as fanquan in Chinese — come with powers that can make or break brands.

Last year, a fan fiction site was shut down after followers of actor Xiao Zhan reported the platform to authorities. They said Archive of Our Own published a novel series that portrayed their star as a trans woman romantically involved with a male high school student.

An increasing number of boycotts over various issues serves as a cautionary tale for idols, reminding of the red lines they shouldn’t cross. Last month, 64 celebrities and agents from the Chinese mainland — including actors Chen He and Dong Jie — attended an “ethical training session” hosted by the National Radio and Television Administration, where they “learned President Xi Jinping’s statements about the industry and professional ethics.”

Despite the boycotts, experts like Xin and Li don’t think “little fresh meat” will lose their luster overnight.

“‘Fresh meat’ equates to traffic, which brands are not ready to part with yet,” Li said. “But only idols who can win over China’s mass consumers without negative news will make it to the top over time.”

Meanwhile, fans like Chen are becoming more skeptical of their idols.

“I dare not to fall for another idol so easily after this,” she said.

Editor: Bibek Bhandari.

(Header image: From left to right, Huo Zun, Kris Wu, and Zhang Zhehan. Photos from People Visual, reedited by Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)