He Who Buries the Trash Is Also Buried by Fate

Editor’s Note: “I spend my middle age five kilometers inside mountains / I explode the rocks layer by layer / to put my life together.” These are the words of Chen Nianxi, a demolition worker from northwestern Shaanxi province, whose dynamic verses capture the hardships of mine labor and have moved readers at home and abroad. He was one of the working-class Chinese poets featured in the award-winning documentary “Iron Moon,” and has been invited to speak at Harvard, Yale, and other U.S. institutions.

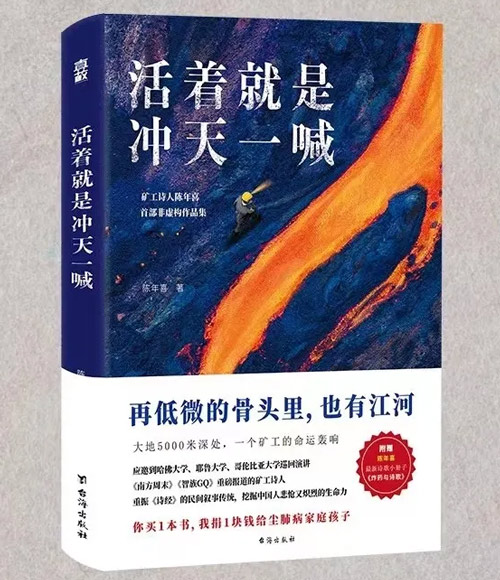

“To Live is to Shout at the Sky,” released in China in June 2021, is his first collection of nonfiction articles. Employing a realist narrative and his unique perspective, he recorded his experience of wandering around western China for two decades, as well as the stories of his colleagues and other acquaintances. The following story, the first in a series of translations from the book, describes the lives of three workers at a landfill in an impoverished Shaanxi county.

1.

When Zhou Dayong graduated high school, he was no longer a teenager. At the time, in underdeveloped places like Danfeng County where educational resources were scant, people finished their education a few years behind schedule. Many started school late, and most had to repeat a grade along the way. By the time they left high school, the boys could grow beards.

Unlike today’s oversaturated industries and harsh competition, back then, in 2004, there were still plenty of business opportunities, regardless of what venture you chose — a stall, a small restaurant, or some other scheme. For a year, Zhou and his classmates made good money selling Weizhi suits, which were popular then in Shaanxi. The Weizhi brand was good, and their suits were high quality.

It was his classmate’s business, and Zhou was just a clerk. At the end of the year, his classmate gave him 5,000 yuan (today the equivalent of $775) — and although his friend didn’t say “you’re dismissed,” the look on his face did. There were so many pretty girls with nothing to do; hiring any one of them would be more appealing than employing a male clerk.

Zhou’s father was still alive then. He’d retired from the position of village head, and, although he was sick, still had some connections that allowed Zhou to get a stable job at a county-owned enterprise, of which Danfeng had two at the time. One was a landfill, the other a winery, and Zhou could choose either. He thought about it for a day and chose the landfill. People might not always drink wine, but their garbage always has to be dealt with. Zhou’s foresight proved prudent; the winery was later squeezed out of existence by its competitors.

When Zhou started at the landfill, it had only opened a year earlier and had been on a trial run since. The previous landfill was Guandao Ditch — a big ditch filled to the brim with trash. Back then, technology and funds were limited. It was simply covered with soil on which trees were then planted, and, at a glance, you couldn’t tell that it was a landfill. But if you looked closely, the trees were sick because of the heat from the fermentation of the underground waste. When it rained, an indescribable smell came out. Even if the grass was high, the cows and sheep wouldn’t want to eat it.

But the Danfeng County Hongyuan Landfill was something else. On his first day, Zhou was stunned. The place was huge, spanning 300 meters long and 110 meters wide, and deep enough to make people working inside it appear to be half their size. There were also shovel loaders, excavators, and construction vehicles — all large equipment rarely seen at the time.

No household garbage was collected in the villages outside the county town at the time, so only a small amount of trash came in. Each truckload was like a drop in the ocean. According to projections Zhou had read, the county’s daily garbage production of 20 tons would mean the new landfill would reach its limit in 30 years. Zhou could work there until he retired.

As a front-line worker, Zhou would take an iron rake to separate the garbage into groups, in order to be disinfected and then buried. He still remembers his first shift. It was the middle of June, the heat was fiercer than any other year, the Dan River was flowing silently in the distance, and the golden stubble of harvested wheat was overshadowed by the corn shooting up. The corn fields surrounded half of the small town and stretched past the landfill. That season, the harvest was like the ocean.

The county town didn’t yet have garbage compacting equipment. The garbage brought over was loose, and there wasn’t a large-tonnage dump truck — one truck would be two to three tons. Dumped from above, paper, plastic bags, and sanitary pads would all fly around with the help of the wind, refusing to settle down.

The smell of feces, leftover food, and composted leaves was overwhelming. Flies were everywhere, like rain. Without a sun hat or a mask, Zhou and two other guys in the middle of the garbage ran back and forth, struggling to get all the trash together. The shovel loader roared, carrying load after load of soil to bury the trash. Landfill workers like Zhou only notice time passing when they feel stubble growing on their chins.

Zhou leaves home every morning at seven and returns at seven in the evening. In 15 years, he has broken three bicycles. The red motorcycle he rides now is still going, but the engine is so weak that he has to restart it over and over before heading out. Its tires have been replaced three times, and, with a broken odometer, it has literally ridden countless kilometers.

The work at the landfill doesn’t require much in the way of skills, and there was no exam. Over the years, the competition had become quite fierce. People were looking for an opening, and pulled strings to share a piece of the pie. Zhou had always wanted to work in an office, but seeing the situation, he understood that work on the front lines wasn’t easy to get, either. So he decided to take his time getting there.

Still, as a rare graduate of one of the county’s best high schools, he functions as the landfill’s writer. Even though it is a relatively small company, it is still a state-owned enterprise. Formal documents, reports, notices, and meeting minutes are required for everything. Whenever the need arises, the manager lets Zhou put down his rake so he can draft these documents.

Because Zhou’s reports are so well-written, many other institutions ask him to write for them — year-end reports, leadership speeches, work briefings, and whatnot, and even the county chronicle office liked him, insisting that he work for them. They even issued a transfer for him, but eventually he chose not to go. Zhou is a filial son, and the landfill is close to his home, allowing him to stay near his sick mother.

She suffers from depression. Nobody understands where it comes from, and even hospitals don’t know how to treat it. Only Zhou knows how terrible it can be — he saw it with his own eyes when it attacked his mother. She banged her head against a wall, banging it so much that she bled. But she wouldn’t stop. She tore at her hair, yanking tuft after tuft out like it wasn’t her own.

Fortunately, Zhou became a regular employee the year before last. Now, there are 30 people working at the landfill. Not even half of them are regular employees — and only two regular employees are on the front line. He’s one of them. At 3,100 yuan, plus a variety of small benefits a month — adding up to nearly 40,000 yuan a year — his salary is more than double that of the temporary workers. His main consideration is his future retirement pension, estimated at 3,000 yuan a month. With that money, both his and his mother’s future needs are guaranteed. That’s his biggest hope for his life, although he’s still far from retirement.

2.

In 2012, five new pieces of equipment were added to the Danfeng County Hongyuan Landfill — a bigger shovel loader, a medium-sized excavator, and three medium-sized dump trucks. It was a last-ditch effort. The landfill is the county’s largest, and the only one equipped for environmentally friendly waste treatment. Although in recent years other townships have built landfills, not many have been put into full operation. Since most of the waste was transported to their landfill, Zhou and his colleagues’ workload doubled. The amount of garbage had reached 50 tons per day. At that rate, it would take less than a decade for the landfill to be bursting at the seams.

At least there were no chemical companies around, so the waste was relatively simple. Because of his writing duties, Zhou often gets to read internal files on other landfills, where the water and air have been polluted, and the workers poisoned. The constant increase in new types of waste put the landfill industry to its greatest test.

Danfeng County set up three additional garbage compacting and processing stations, so a large amount of the household garbage was compacted — becoming a lot easier to handle. Because the landfill work was no longer as labor intensive, some of Zhou’s colleagues were reassigned to the compacting stations. Zhou stayed at the landfill, but his partner, nicknamed “Xiao Huang,” was assigned to the west city garbage compacting station.

“Xiao,” meaning small, refers to his short size. Huang is in his early 40s. His son is a senior at the county town high school, and their home is in the countryside to the north, where, in the barren mountain land, few crops or trees will grow.

Being poor, Huang previously made his money by going to the river to sieve sand to sell. In the countryside, with shoddy roads and limited economic activity, there wasn’t much ongoing construction, meaning sand sold at a low price. So Huang bought a second-hand tricycle to take the sand to the county town, where there was a modest building spree thirsty for sand.

Huang has been driving for over ten years. Early on, he drove motorized three-wheelers at the local mine, making trips to haul rock out of the mine shafts. The mine was low and narrow, and had almost no light. After a few years he had become a skilled driver, but he never got his license — mines weren’t part of the roadway system and thus no one regulated them. By the time the mine was exhausted and Huang needed to drive on the roads, he failed the written test. Even though he’d memorized the answers until he was dizzy and tried for three years, he couldn’t pass it.

Without a driver’s license, Huang had to drive at night. From the north mountains to the county town was over 50 kilometers, and he’d run two roundtrips every night. He’d start the first trip just after dusk, and finish the second trip just before dawn.

On one April night, so uncommonly dark neither the moon nor stars were visible in the sky, the headlights of Huang’s three-wheeler went out. He checked all the wiring but couldn’t figure out why. The nights are short in spring, so he didn’t dare to delay any longer. He found a miner’s headlamp and put it on. The strap on the headlamp was too short, and it strangled his head until it felt raw. He loaded up a huge amount of sand and took off. The tired three-wheeler let out black smoke the whole way.

Huang’s route from the north mountain to the county town meant he had to cross Yuanling, the highest ridge in Danfeng County with an altitude of around 1,500 meters. The snow falls in winter and doesn’t melt until winter ends. The road is steep, and the curves are many — but time did not allow Huang to linger. Construction bosses only bought sand in bulk, so he had to finish his second trip. Then, on one curve, Huang’s three-wheeler hit a motorcycle with its headlight out.

Its rider was a man dealing tianma, a medicinal herb. Tianma is valuable, and there was no shortage of a market for it. At the time, there was a particularly large amount of tianma on the northern mountains, and there were vendors selling it everywhere. But whenever there’s a profit to be made, there are people fighting for a share. The tax bureau and the commerce bureau would set up toll gates to collect fees. Just like Huang, the vendors would go out at night to avoid the authorities.

The man broke a leg and two ribs. Huang had to come up with 100,000 yuan at once — but his family had no money. He borrowed from relatives and friends, finally selling his three-wheeler to come up with it. From that time until his son’s senior year of high school, Huang’s family was stuck in a hole of debt.

At the landfill’s compacting station, Huang is a temporary worker. His salary is only 1,500 yuan, with no benefits and no days off. He used to think about jumping ship, but these days he’s given that up. He’s too old to deal with the upsets, and his son needs money every day — he can’t afford to be picky about it.

Huang is a loader and drives a forklift, so he gets to make the best use of his skills. There’s an advantage to being a loader, which is that every little thing passes under his eyes first. Although scavengers have already sifted through the trash before it reaches the landfill, some useful things are still left behind, like old clothes, cardboard, and even old electrical appliances.

Once, there was a bag in the trash, and Huang rushed to stop the compacting machine. He opened it and found a laptop. After work, Huang sent it to the computer repair shop; after it was repaired, it worked quite well for his son.

Huang also picks out old scrap items to earn money, enough for his daily necessities. People say that, sometimes, scavengers can find a bag full of jewelry or maybe money, but Huang has never found anything like that. The small town isn’t wealthy, so no one would be that careless, he figures.

Huang knows that there are many people who would like to have his job, but he is confident that his top-notch skills mean he won’t be replaced. His wish is to work until the age of 60, or at least until his 50s, when his son will have graduated from college and have a job. Then, when his final day comes, he’ll be able to face his child’s mother and tell her he did alright.

The year she passed away, Huang was 25. Time goes by in an instant — a flash that somehow spans 18 years.

3.

One October morning, still some time before the arrival of winter, the weather was already cold enough to freeze the outdoor faucets. Zhang Kezi took a full kettle of boiling water and slowly poured a long, thin stream of water onto a tap. The kettle was half-empty when the faucet finally started to drip water. He picked up a basin of water and began to wash his face, brush his teeth, and shave, which was his morning ritual. Zhang drives a garbage truck, but to distinguish himself from the trash, he tries to take care of his appearance.

As a contract worker, Zhang’s salary is lower than Zhou’s but higher than Huang’s, and he gets some benefits — like two days off a week. Before starting at the landfill, he drove trucks in the army, transporting supplies across the Tibetan Plateau for 15 years.

Zhang’s wife Juanzi has been working in the provincial capital for several years. He doesn’t know exactly what her job is. In any case, she comes back once or twice a year, and always dresses in an eye-catching way, which makes his heart clench. Zhang has forgotten when Juanzi started to come home less and less. At first, they would call each other if she didn’t come back. Later, the phone calls became less frequent, and they didn’t have much to say to each other.

Zhang sprayed some cologne onto his shirt. Today, he would be going to see Juanzi.

But he didn’t know where she worked, only that it was in Zhangbagou, an area in the provincial capital Xi’an. One time, on the phone, he heard the name on an announcement from a bus she was on, so he remembered the station name. He guessed that Juanzi must live in the area, because it was very early in the morning and she couldn’t possibly have been far from home at that hour.

He washed his truck and carefully tended to the cab. It had been half of his home over the years. Sometimes he slept in the cab when he didn’t want to go back to his rental. He put every object in order, and paid special attention to cleaning the spring-action doll on his dashboard. In his eyes, that was Juanzi.

There are five trucks at the compacting stations around the county town. With no fixed assignment, they go wherever they are needed. After the compacting process, the garbage load is five times the weight of a truckload of loose garbage. Zhang has to make five or six trips every day. He likes this job very much. Compared with driving on the Qinghai-Tibet Highway, this job is much easier, and safer.

He knows that although he is not a regular worker, as long as there was no special reason, the landfill wouldn’t casually lay him off. Every day, he feels like he’s doing some sightseeing when he drives the truck into and out of town, and he has grown familiar with almost every street, alley, and building. He fantasized that one day he would have some money and would be able to buy a big house in the nicest part of town. It would be his permanent home. Several years ago, Juanzi wanted to buy a house here, but they didn’t have enough money.

After a train trip, he arrived in Xi’an, and then, after a subway ride, in Zhangbagou. Zhang wanted to give Juanzi a call and tell her that he had come to see her. He stood under the bus stop sign for the entire day, but couldn’t do it. He suddenly felt nervous, but what he was nervous about he didn’t quite understand.

He spent the next day wandering around. He thought that Juanzi would surely take the bus here, or pass by. Even if he didn’t see her, she might see him.

However, in the end, Juazzi never passed by or got on the bus, and Zhang went back to Danfeng. He wanted to wait another day, but only had two days off.

On the third night, he finally received a call. It was Juanzi’s number, but not her voice. The person on the other end told him that something had happened to Juanzi. She’d fallen from the eighth floor of a building.

Three days later, Zhang met Juanzi at the funeral home. He learned that, for all these years, Juanzi had been doing “that kind of work.” She had six-figure savings in her bank account.

The money was just enough to buy a house in the county town.

Zhang would never have thought that this would be Juanzi’s end, but, learning about her job, he wasn’t surprised. It was a despised and dangerous job. But Zhang knew that the money wasn’t dirty — just soaked in blood and tears.

He never thought about buying a house again.

A version of this article was originally published by The Paper and republished by TrumanStory Books and Taihai Press in the book “To Live is to Shout at the Sky.” It has been translated and edited for length and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Xue Yongle and Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Icons: Iconscout/People Visual)

(Header image: A view of the landfill where Zhou Dayong works, 2018. Courtesy of Zhou Dayong)