China’s ‘Drifting’ Migrant Mothers Tell Their Stories

When I asked Mengyu, a 53-year-old domestic worker, what she thought of the first two books I had edited, she was unsparing.

“If I had a well-educated mother and lived with my parents in the city like the writers in those books, I wouldn’t be complaining the way they do,” she replied. “I’d be so happy I could die.”

Mengyu is one of the contributors to the latest edition of the “Writing Mothers” (WM) series, an ongoing collaborative writing project I initiated in July 2017. The first two compilations — the ones Mengyu was referring to — were written by a mix of 14 contributors and myself. We shared our observations on the ways policy had shaped the lives of our own mothers, how mainstream discourse depicts and discusses mothers, and how the very concept of motherhood has been highjacked at various points in history.

In the process of producing the first two books, I never meant to exclude non-urban mothers, yet in retrospect, most of our contributors were native urbanites, practiced writers, and, in many cases, beneficiaries of overseas education who had at least a passing familiarity with alternative lifestyles. While I expected our words and ideas to spark controversy — and we indeed had readers accuse us of disrespecting traditional family values — I was struck by the struggles of readers like Mengyu to empathize and connect with the frustrations and pains of young urbanites.

It pained me to see such a class divide in the responses to the first two compilations, and I wanted to understand how to better connect with women like Mengyu: What matters to her and how have her experiences shaped her worldview and priorities? To find out, I decided to put together a new compilation focusing on women from rural backgrounds. The product of those efforts is the fifth book in the WM series, “Kindemic: Words and Worlds of Drifting Female Workers,” which centers on the vicissitudes of this vulnerable group and their families amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

The process was not always smooth. At first, I created a single chat group for potential contributors from all different backgrounds, thinking it could facilitate or inspire dialogue, but to little effect. Then, in 2019, I started a separate project to specifically facilitate writing by “drifter” women workers, including writing classes, workshops, and reading groups, both in and out of a traditional NGO setting.

The choice to call them “drifters” was intentional. The term “migrants” still implies eventual entitlement to the benefits of citizenship. But Mengyu and her peers do not enjoy those protections or access to other benefits like education, health care, and welfare. They work odd jobs on production lines, in the service industry, or as caregivers, and they cannot use the same safety net as their urban-born or officially registered peers. The precariousness of their situation as “drifters” has only become more salient in the wake of the pandemic.

Once we started workshopping together, it was clear that these women were bound together by shared experiences very different from those of my previous contributors. Growing up in villages without schools, they’ve faced extreme sexism, the risk of early or even arranged marriages, and urban discrimination. The disconnect was stark. Whereas the writers who contributed to the first two compilations spoke constantly of their yearning to leave their families behind and be free, those who grew up in drifting families wanted nothing more than to stay with their parents.

Even their reactions to the same policies and ideas differed radically. While my urbanite contributors talked about the harms of forced abortion and the alienation of being raised as an only child in the city, one female drifter wrote about how grateful she and her mother were for the one-child policy. She described seeing it as a form of protection for rural women who otherwise had little access to contraception and were vulnerable to being treated like walking “baby-making machines.”

Working with these women challenged my prior assumptions. I thought that a life of oppression would naturally gear a writer toward straightforward realism, but many of the initial drafts I received were full of ornate stylistic conventions that obfuscated more than they revealed. The women adhered rigorously to the style of writing that is drilled into kids throughout primary and secondary school; they strung together sentimental clichés and truisms, deliberately imitated the style of classic literature, and overused rhetorical devices.

This worship of stylistic conventions is itself a sign of the inequality that female workers have faced throughout their lives. Blind imitation of rhetorical devices from “classic works” by mostly male authors implies a hierarchy of words — and expression — that suppresses their self-confidence.

As we worked together, I found myself rethinking the very potential of writing as a medium. While writing is often hailed as a way to give free rein to one’s creativity, it also has the potential to discipline and even confine individuals. For many female workers, the written word actually restricts their capacity for critical thinking and self-reflection and reinforces their acceptance of an established order. Mengyu, for example, tried to denounce the domestic violence she’d experienced and reject the insularity of rural family life, but her essay still fell back on a cliché about the “harmonious resolution of conflict in the home.” Is this really what she feels?

I found myself actively intervening in these female workers’ writing processes and challenging them to describe some of their experiences from different perspectives to get their readers thinking. For some, the results have been remarkable. For example, Yanzi, a female worker currently based in Shenzhen, initially wrote a poem in which she both praised the city and prayed to it to let her and her children settle down there. After reading it, I suggested that she start by telling the actual story of her relationship with the city. She gave it a try and came back saying that, ultimately, if she wanted to write a story about Shenzhen, she had to start with her childhood in a remote and poor village. Her story transformed from vague lyricism to courageous realism; it was exactly what I hoped to see.

Of course, these changes don’t just happen out of the blue. They require a personalized, experimental, boundary-blurring editorial dynamic. This forced me to grapple with difficult questions: Who am I to say how these women should write? And how much do I really know about the author and what they want to express?

All I can say is that I did my best to create opportunities to live together and with my contributors. In the tradition of “prefigurative politics,” sometimes you have to be the change you want to see in the world. I went to their homes and invited them into mine, and the more we worked together, the more flexible we became and the more we learned from each other.

Do such interactions and engagements really point to a potential future in which people from different social classes can understand and support each other? I admit I’m pessimistic. Over the course of producing five “Writing Mothers” books, the bulk of the authors I’ve worked with fit into roughly three categories: middle class women working within the state or public sector, educated women outside this system, and now “drifters” living at the fringes of urban society.

The first compilations were largely drawn from women in the second category, educated women outside the traditional confines of bourgeois society. These authors were largely unified by their language and shared post-materialist desire for ideological independence, both for themselves and others. Drifting women, on the other hand, are less concerned with freedom than stability and being able to meet their material needs, which was surprisingly similar to the perspective of most system-bound middle class contributors. Ultimately, our needs, desires, and priorities are still largely determined by our socioeconomic backgrounds.

Pessimism notwithstanding, my experiences working with these drifting women gave me some cause for hope, especially after comparing their first and final drafts. Again, there are hard-to-answer questions here about authenticity, purity, and my role in the creative process, but I generally find myself inclining more and more toward the view that purity isn’t necessarily superior to the results of a moldable, cooperative, and hybrid process.

The contemporary world has developed a set of “social distancing” techniques which blind us to the inherent hybridity and fluidity of our identities and keep social classes apart. Like safe writing, the “safe” world of social class distancing comes at the cost of genuine connection, meaning, and conversation. Yet these characteristics give us the chance to see beyond the immediate problems and realities of our social class — if we can recognize and embrace that opportunity.

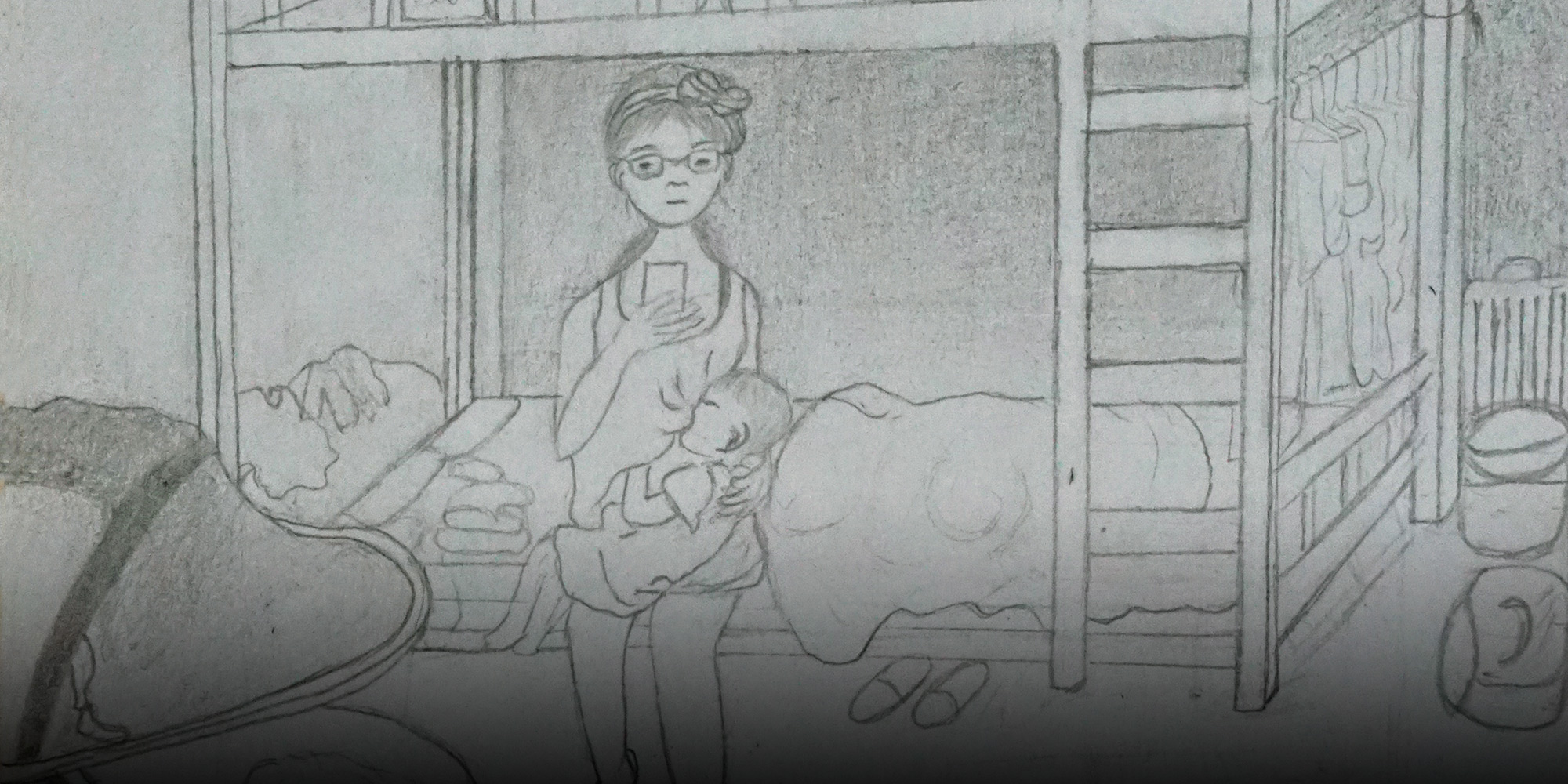

For example, while collaborating with the authors, we landed on an unexpected means of communication: drawing. In addition to writing, I encouraged them to express themselves through sketches and illustrations. Perhaps because they never had art teachers breathing down their necks, telling them they had to draw in a certain way if they wanted to be successful, their art felt far more connected to their authentic selves, and we ended up including 10 of their illustrations in the latest volume.

For all the misunderstandings and debates I had working with contributors from backgrounds so different from my own, it was worth it in the end. Already, I’ve invited two authors who are not “drifting” workers to respond to the new volume’s essays, just as I had asked Mengyu what she thought of the first two. And so the dialogue continues.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: An illustration by Xiaoxi, a contributor to the “Writing Mothers” series, from “Kindemic: Words and Worlds of Drifting Female Workers.” Courtesy of 51 Personae)