A Miner’s Verse: Through Peril and Pain, Just Words Remain

Chen Nianxi was born at 8 p.m. on Lunar New Year’s Eve, 1970. The fortune-teller present for the occasion needed no detailed calculations for his dire prediction.

He told Chen’s mother: “A person born on this day will have a bad life. The world’s gods and people are all on vacation, and no one will care for him. He will be alone.”

Chen never believed in fate but now, at 51, those first few words after his birth have returned to haunt him.

He’s never actually celebrated his birthday — it was always overshadowed by the Lunar New Year. Most were bleak, like in the winter of 2016, when he lived alone in Beijing. Everywhere, stores and supermarkets were closed, and all he had at home was a packet of instant noodles.

He cooked and ate it in silence, alone, to celebrate his birthday. He says he couldn’t help but wonder if the prophecy was actually true.

Back in his hometown, his family usually made five or six dishes along with rice for Lunar New Year’s Eve. After the wine and food were gone and the candlelight extinguished, his wife would occasionally remember, and then say to him, “You’re another year older.”

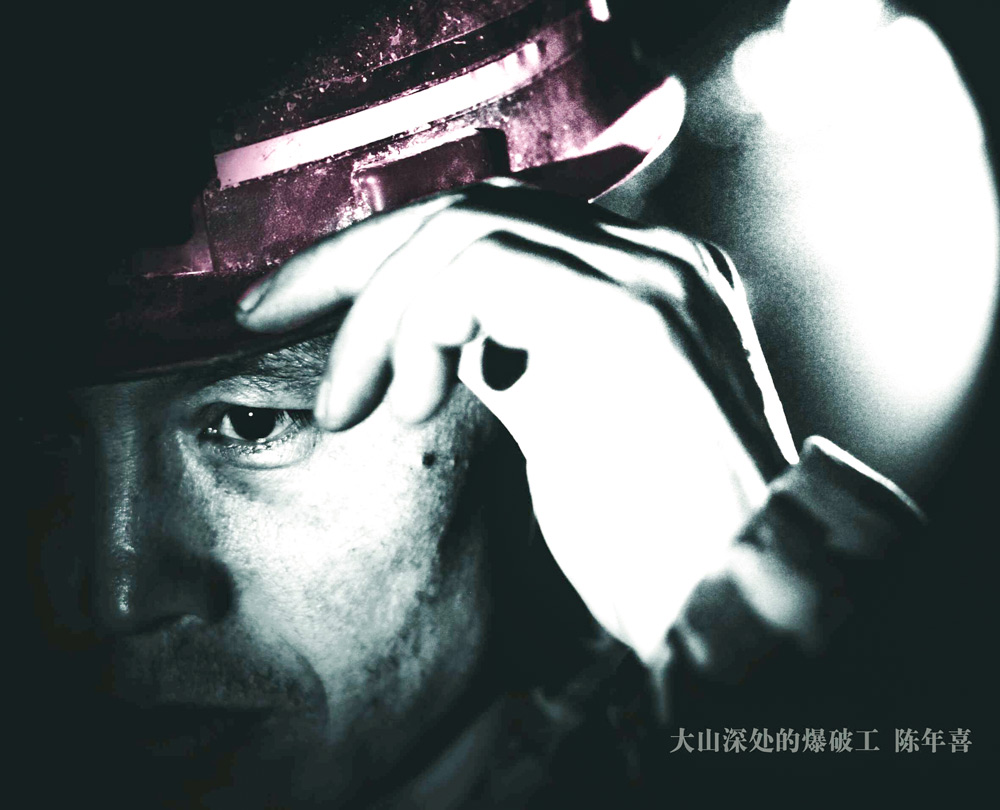

Chen spent the majority of his adult life in mines across China, eventually becoming a sought-after demolitions expert, losing friends and comrades along the way.

Last year, just when he was considering moving to Tajikistan to try and make a fortune in demolition, fate caught up again — Chen was diagnosed with pneumoconiosis, also known as black lung disease.

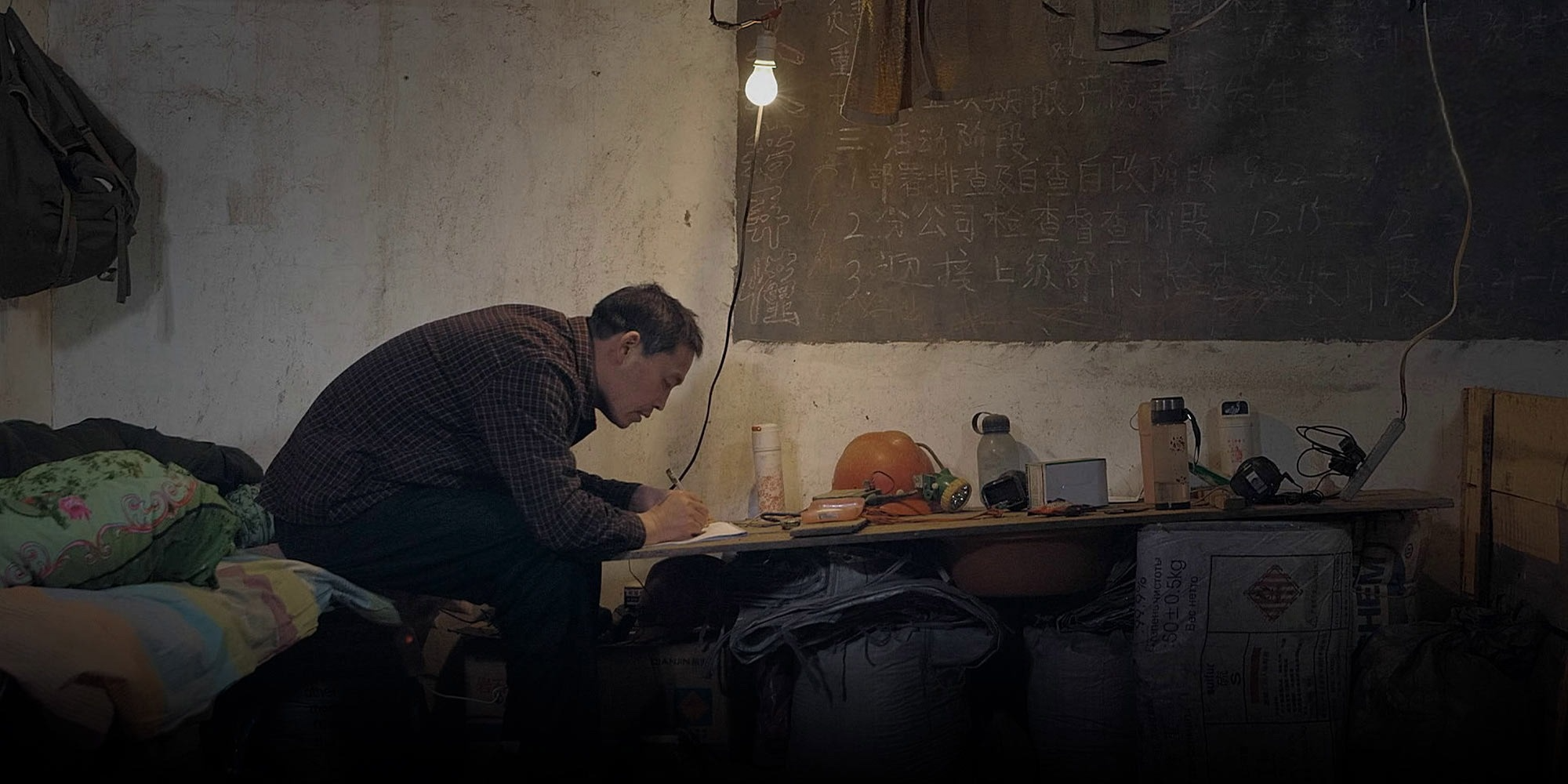

Through thick and thin in this hazardous profession, Chen found solace only in writing. His canvas: the mines, the workers who toil beneath, and life in near perpetual seclusion.

It put him on a different path. Today, he is renowned as the “miner poet.” After 16 years in the mines, Chen was featured in a documentary, “The Verse of Us,” and participated in a reality show.

Since then, he’s gradually gained fame, but he wants more; from himself and from life.

Beneath the surface

Chen grew up in Danfeng County in Shangluo, in the northwestern Shaanxi province, close to the Dan River. He lived in a slightly wider area in a mountain hollow, along with a few other families. A few kilometers further, in a more open area, were five or six more families, and each far apart from the next.

“My hometown is very sparsely populated. There’s a road along the river, which disappears when there’s a big flood. It’s an eternal struggle between rivers, dirt roads, and highways,” he says.

In the mountains, communication relies on shouting — the echo allows voices to travel far. Before telephones or communication equipment arrived, it’s how families spoke to each other.

They even hummed folk songs amid the mountains. “The elders, amidst such a hostile environment, liked to sing alone in the mountains. But their songs could be heard from far away, so someone on the other side of the mountain might respond,” says Chen.

With simple tunes and rustic lyrics, Chen still treasures these mountain songs, and learned a lot from them. “I know some of the historical stories from such songs, not from books. They tell you a lot about human relations and ethics, understanding the whole world, and destiny. The character of people, the character of individuals, can be seen in them,” he says.

In 2003, a deep bond with his mining friend nicknamed Wang Er began with such a song. They had very different personalities but were united by the seclusion of working in the same gold mine in the central Henan province, far from their families.

During one particularly lively conversation, Wang started singing “Silang Visits His Mother,” a Peking opera song about Yang Silang, who was taken from his hometown under the Northern Song dynasty, while resisting foreign invasion by the Liao dynasty.

Yang eventually married a Liao princess, and 15 years later, learned that his mother was leading troops north against the Liao state. In the opera, Yang sneaks out at midnight to visit his mother. Wang and Chen were so moved by this scene that both cried.

Their friendship ended abruptly in 2013 when Wang died in an explosion. In the same accident, Chen lost hearing in his right ear.

Writing about his workmate’s death, he was unusually calm, probably because such accidents were frequent.

Wang Er lies dead at my hands,

But also at his own hands.

I shouldn’t have messed with the blasthole,

He shouldn’t have made the fuse so short.

But death, that’s only a matter of time — no one can stop it.

In demolition, life is tied to your helmet. He says: “You go ten or so hours a day without food or drink. If you’re lucky, you can take a bottle of water and an apple. When you enter the mountain, you go 5,000 meters, then 10,000 meters, and then 100,000 meters, digging step by step.”

The slightest mistake can cause a collapse, lead to a lack of oxygen, cave-ins, water seepage, or mechanical failures. Chen says he woke up every morning, and went into the mine. If he got home safely at night, he was relieved. Day after day, over time, he became numb to the constant risk.

“When you go to work, you make some calculations and say to yourself: ‘Don’t have any problems today,’ because everything is hard to predict. Over the decades, you’ve always wanted to leave — but what will you do if you leave the mine altogether? Other industries are completely new. Can you go two or three years without income? All this forces us to take it one day at a time in this industry, and to just keep going back down,” says Chen.

Demolition workers often change sites, and each time they join a new one, recertification is mandatory. “From the performance of explosives, to using them, to responding to any situation, it’s all systematic,” he says.

Chen was the most certified demolition expert among the workers, passing more than a dozen exams. Once, a site owner said, “There’s a job here if you come, though no one has done it for a long time.”

He and his friends went to look at the blasthole at the site. It was marked with a talisman of yellow rice paper that had curved, vermilion symbols on it, and it looked frightening.

They immediately knew that an accident must have recently occurred. But since they had come all this way, there was no backing out — they just had to proceed with caution.

Chen vividly recalls the time he came close to death. “We had reached a very deep place in the rock, where it was very soft. My brother and I were in front, and while working, the water stopped. We immediately judged that midway through the tunnel there must have been an accident, so we quickly got out,” he says.

The moment they exited the mine, they heard the tunnel collapse behind them. As they looked back, the crashing rocks crushed and smashed their water pipe completely.

If one isn’t alert enough, or inexperienced, or a little slow, they can easily become trapped inside. He says, “When a whole tunnel collapses, there isn’t much oxygen inside. You’ll have a hard time holding on for more than a few hours. The collapsed rocks need to be taken out before you have space to connect to the outside.”

But how long it takes to deal with a pile of rocks is anyone’s guess, and when trapped inside, your life is no longer in your hands.

It was only on leaving the site in 2015 that Chen really began to reflect on his life in the mines through his poetry. After 16 years in the mines, he was amazed at the resilience of people given the lonely environment, the constant reflections on the living conditions, and the way each person fought for their lives.

They often had problems with the machines in the mines, and were out in the middle of nowhere. If the manufacturer sent a technician, a roundtrip could take ten days — a delay they couldn’t afford.

Chen says in such mines, some workers were exceptionally resourceful and could quickly identify a problem, and immediately resume production. He says, “After spending time with them, it makes me feel like life actually has infinite possibilities. Everyone has their own preferences, and even their own obsessions.”

For him, 16 years as a miner was the motherlode of inspiration in itself, worth writing about for a lifetime. “When I write, I recall all the details of my past experiences. I’d say that mining is part of my destiny, engraved into my flesh and blood,” he says.

He believes that although people’s lives are different, they are all connected through a fundamental helplessness, loneliness, and a sense of distance from the world. This is also what Chen pursues in his writing.

Reassembling his life

Growing up, Chen Nianxi loved reading, and every family nearby subscribed to a magazine or two — folk literature or ancient and modern legends, or newspapers.

At the time, without the internet, cell phones, or even television, many homes only had old thread-bound books hidden away.

One book would circulate across the whole village, and almost every resident eventually ended up reading the same tome. When one person finished, they immediately gave it to the next family, who would in turn return it when done.

Once, Chen borrowed a copy of “Investiture of the Gods” — a 16th-century epic — from a friend. “It was quite thick, but he only gave me one night to read it. I used a kerosene lamp to read it overnight since there wasn’t electricity at the time. I adjusted the light to a large flame to make it bright enough. There was so much smoke from that lamp that when I got up in the morning and blew my nose, it was all black.”

During Lunar New Year’s Eve, families in his hometown reveled in making handmade noodles, which were thin and brittle, and then wrapped in layers of newspaper. Newspapers were specifically saved for such occasions.

But just before they were used to wrap the noodles, Chen went around the village to borrow them all. After reading around 200 newspapers, he’d return them.

Even through his mining career, Chen never broke his reading habit. During his days as a demolition expert, after work, he sometimes went to an abandoned workshop where newspapers were plastered across the walls. After reading one, he would splash water on the wall, carefully peel off the page, and then read the other side.

His favorite author is Chinese novelist and Nobel laureate Mo Yan, whose unique view of life and history, according to Chen, was shaped by his rural childhood as opposed to reading textbooks. This made Chen feel a kinship with him.

Once they graduated high school, most people in his hometown immediately got busy. “After joining the workforce, the first thing your family needs is food. Second, you build a house. Once the house is built, the matchmaking will begin. Then you get married and have children — and so life goes on, in this order,” says Chen.

In Shangluo, the whole family worked to build a house. For jobs even five people couldn’t manage together, the village turned up to help; they didn’t require money — the villagers were just like extended family.

Chen’s first love was a woman from the city. At that time, he vaguely held on to the fantasy of marrying someone from the city and changing his rural destiny. He submitted articles to city magazines and attended the correspondence courses they ran.

In 1991, he enrolled in a class in Luzhou in the southwestern Sichuan province for 15 yuan ($2), where editors revised his work for six months. Outstanding pieces were selected for publication in a newspaper. Doing the course, he became pen pals with a woman from the northeastern Jilin province. They corresponded for over a year.

In the winter of 1991, the woman asked him to visit her home. Chen, then 21, took an atlas with him and traveled across the mountains to Luoyang, Henan province. There, he caught a train to Beijing, before finally reaching the last stop, Shenyang — a journey of four or five days.

When he left the station, it was 20 to 30 degrees Celsius below zero, so cold that he couldn’t even walk. He eventually spent three days at their home. It was all he needed to recognize the gap between fantasy and reality.

“Theirs was a family of workers, living in a particularly low-ceilinged house in a shantytown. I couldn’t stand up straight inside. Five of them shared a large bed, using firewood to heat the bed-stove, keeping warm that way in the winter,” he recalls.

Moreover, the mandatory urban and rural hukou or household registration posed an additional obstacle. “I had neither the hukou nor a job. I didn’t even have a place to stay, so how could I go on? I didn’t say much for a couple of days. I just sat and pondered it all.”

Such is the winter in northeastern China that factories stop operations, and people don’t work much. Chen was hesitant, but he asked the woman: “How shall we live, and how will I earn money?” But she was adamant, and replied, “I earn a salary, so I can support you.”

But Chen waved her off, “I’m a man, how can I rely on you?” He went back home, but they stayed in touch, writing letters. His letters often took about a week to reach her, and as much time for her reply to reach him.

“The words I wrote those days were on composition paper. It’s very strange. Even if I wrote ten pages, there weren’t any spelling mistakes, not a single word that needed correction,” he says.

Both had kept all their letters, until a big flood in the city where the woman lived washed hers away. Those Chen received were ultimately lost during his constant relocations.

In 1998, Chen eventually married another woman. It was considered a late marriage in his village. The wedding photo, which cost over 100 yuan, was framed and hung in the living room. A year later, as his family wished, he became a miner. Since his hometown was close to the gold mines, it was the desired profession of that time, and offered decent pay too.

In the beginning, he saw his wife just once every six months. It barely got better after they had a son.

Those days, he worked demolitions underground and heard little about the world above. His son grew up, and didn’t want to call him “father.” Sometimes, he managed to stay home for a month or two, and during this period, after spending some time with each other, his son even reluctantly called him “father” once or twice.

“Family is the only base camp, right? Depending on our family, we can charge or retreat. If I had no family, I think all my efforts would have been meaningless, a person drifting through the world,” he says.

Chen launched a blog in 2011. Two years later, his mother became seriously ill with esophageal cancer, and one night, unable to sleep, he wrote a poem titled “Fracturing.”

I passed middle age at a depth of 5,000 meters.

I detonated rock formations one by one,

And doing so reassembled my life.

Family is far away, at the foot of Shang Mountain.

They are sick and their bodies are full of dust.

Then, in 2015, after the documentary “The Verse of Us,” about Chinese worker poetry, was released, Chen became a celebrity overnight. Many learned of the name Chen Nianxi, learned about new workers’ literature, and learned about his subsequent poetry collections.

He was invited to the U.S. to speak at Harvard and Yale; he participated in variety shows, writing lyrics for singers; he wrote non-fiction; and journalists came in droves for interviews.

Chen’s visit to the U.S. coincided with the 2016 election. On his first day there, he went to the Empire State Building and asked himself, “Is there steel that I dug up in this building?”

But he immediately rejected such thoughts. Chen believes they are the product of man’s lack of confidence in himself, something that is idealized to demonstrate infinite power. But in reality, he says, “It must have been through people like me at the bottom who produced the materials that led to such a magnificent building.”

He stayed in the U.S. for 21 days, traveling from the East to the West Coast, visiting several cities and seven universities. He says that while the trip didn’t leave a very strong impression on him, the literary exchanges gave him a different kind of excitement.

“I originally thought workers’ poetry was absolutely unknown in a country like America. But in the exchanges, their participation was high — even higher than at home. People asked lots of questions, and the scenes of life they presented to me were both familiar and strange. Although there are significant cultural differences, there is still a consensus worth exploring,” he says.

On returning to China, Chen found work at a travel agency in the southwestern Guizhou province. In his words, the main task was “bragging about the company,” and leisurely clerical work brought little satisfaction. He says, “It’s useless. Back home, when people talk, they still just want to compare how much they earn.”

Chen worked there for three years, until he was diagnosed with pneumoconiosis.

Occupational hazards

Pneumoconiosis has a latent period of five to 10 years. Chen Nianxi worked on the mountain from 1999 to the summer of 2015 — 16 years in all.

Though he’s been coughing for a long time, there were other small warning signs. In the summer of 2016, in a hostel in Beijing, a photographer was documenting his daily life. A chill entered his back late one night, leading to a long, serious cough.

At the time, it had only been one year since he had cervical spine surgery, and each cough resounded with even more pain. With his son in high school, it was a time when the family spent the most money. He knew he could no longer afford to go to the mine to earn a living.

That night, he took the last 50 yuan he had to the community clinic for cough medicine. But the doctor said that without a hukou, it would be more expensive. He returned empty-handed.

On March 23, 2020, after a cough that lasted over a month, Chen finally decided to get checked, and he was confirmed to have pneumoconiosis.

Pneumoconiosis is the most common occupational disease in China. According to official statistics, by the end of 2018, China reported 975,000 occupational disease cases, of which 873,000 were pneumoconiosis — about 90% of the country’s total occupational disease cases.

“So it’s my turn,” Chen thought to himself at the time. He says he still has many things he wants to write about. But because of the illness, it felt like all roads had come to an end. He felt it was useless to tell his wife, believing she wouldn’t understand and would only get stressed.

That day, when it was almost dark, he told the director of “The Verse of Us” about his diagnosis. The two have been friends for years.

Chen says he’s also witnessed many colleagues get this disease, and knows well what terminal pneumoconiosis entails; the disease is irreversible, and one can only fight to delay death. As it worsens, it may trigger respiratory failure.

Before Chen left the hospital, the doctor wrote some instructions: “keep up with nutrition, and don’t catch a cold” — a phrase as ambiguous as the doctor’s wild handwriting.

“Pneumoconiosis doesn’t kill you; it’s the complications that do it. I asked the doctor what direction the complications would go in, and he said he didn’t know. According to the prescription, it costs 3,000 yuan ($470) a month for medicine, so I reduced some of the medicine to save money. Since countless complications are possible, what medicine can stop them all?” says Chen.

He returned to his home in Shangluo. Occasionally a journalist arrived to stay with Chen and his wife, write something, and leave. Sometimes he traveled to Beijing to star in a documentary. Other than that, life was no different.

The government granted his family a better house in the county, where there was a post office and internet connectivity, so he moved there. Reading, writing, buying his own books, signing and stamping them, and sending them out by mail — that was his life. Meanwhile, his income came from the little money he earned per book.

His wife still farms at their home in rural Danfeng, which is part of Shangluo. Years ago, she grew wheat, but over the last few years, it’s been chaff. She is meticulous, and every piece of land needs to be filled in smoothly before planting begins.

“She’s a particularly strong person, and does everything herself. The land is barren and doesn’t grow crops well, so it’s the same for everything you plant,” he says. When the farming season is busy, he helps tend the land.

“In fact, there are still a lot of things left to write. But mainly because I’ve been idle, and haven’t been in good health, over the past two years, I haven’t written very much,” he says.

In June 2021, he published a new book, “To Live Is to Shout at the Sky.” One of his favorite works is a poem “Train Through 2004.”

K1043, Car 5, No. 45

The place where we first met

This poor man’s green train

Drove into history some years after you left

The day you were buried

I was buried in another province

You were buried on a hillock

I was buried with a serious illness

The subject of this poem is a friend nicknamed Jiangzi. They met on a train to Xi’an in 2004, and, because of their similar backgrounds, quickly established a deep bond. After going their separate ways, Jiangzi continued as a truck driver and Chen returned to demolitions.

“This truck driver, too, bounced around, all over the earth. Many people think the life of a truck driver is guaranteed, and the work is very romantic. In fact, driving alone through the vast Gobi Desert, a person has to overcome all kinds of difficulties, and many fears. It’s a strong test to see if he has the ability to manage stress and to survive while maintaining his psychological state,” says Chen.

Jiangzi died in a car accident at the Karakash River due to a car rollover. That same year, Chen was told of his condition.

I asked him: “If you didn’t have pneumoconiosis, what would you most like to do?”

“Go to Tajikistan. I got a passport before I went to the U.S., so it would be easy for me to get over there.”

“I still have this ambition. I know people working demolitions in Tajikistan, and some have made 900,000 yuan in three years. That’s an astronomical amount to me — for any of us. I’m still thinking about taking advantage of the last bit of my life, and taking a shot at it.”

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Xue Yongle and Apurva.

(Header image: A still of Chen Nianxi from the documentary “The Verse of Us.” From Douban)