Chinese Vocational Schools Have a Discipline Problem

Last year, I followed several teachers at a vocational middle school in the eastern Jiangxi province as they made house visits to prospective enrollees. I was surprised by how much of their sales pitches revolved around the school’s “closed paramilitary management” style. Parents seemed more pleased than put off by the idea of a little military discipline for their children, often nodding their heads approvingly when the term came up.

Later, while conducting fieldwork at the same school, I saw for myself what “closed paramilitary management” means. Each student’s daily schedule is carefully planned and monitored: Morning exercises are held at 6:30 a.m., after which students help clean the school before queuing up for breakfast at half past seven. Classes begin at 8:10 a.m. and run until lunch. After lunch, all students are required to return to their dormitories to rest, then they attend more classes and self-study sessions until 9:30 p.m., after which it’s back to the dorms. It’s lights out at half past 10. Like all high school students in China, newly enrolled vocational students must undergo a week of military training at the beginning of their first semester; unlike students at non-vocational schools, vocational freshmen continue to undergo military training every morning for their entire first year.

To ensure student safety and discipline, the school where I conducted my fieldwork also maintains a strict “closed management” protocol. Non-boarding students need to have a slip issued by the school and signed by the head teacher to leave school grounds, while students who live in the dormitories must present a signed slip if they want to leave on weekends. Cameras are everywhere: A huge screen in the principal’s office displays an eight-by-eight grid of real-time surveillance footage that shows the school’s every nook and corner. As if that wasn’t enough, there is at least one teacher posted on each floor of the student dormitory to ensure students are resting during the designated hours. It’s no exaggeration to say that students are micro-managed every second of the day, even when they’re asleep.

This is nothing new. Since the 1990s, terms like “paramilitary” or “militarized management” have been prominently featured in Chinese vocational schools’ admissions brochures. More striking is the fact that, at a time when non-vocational schools are increasingly embracing less rigid and more modern approaches to teaching and scheduling, vocational schools continue to pride themselves on their strict, military discipline, often to widespread public and parental approval.

Understanding why requires looking beyond school walls. High school is not included in China’s compulsory education system; instead, students take a high school entrance exam in their final year of middle school. Although there are exceptions, students with higher scores generally choose to attend “ordinary” high schools, which focus on preparing pupils to take the college entrance exam. Those who do not score high enough on the exam often have no choice but to attend vocational school if they wish to continue their education.

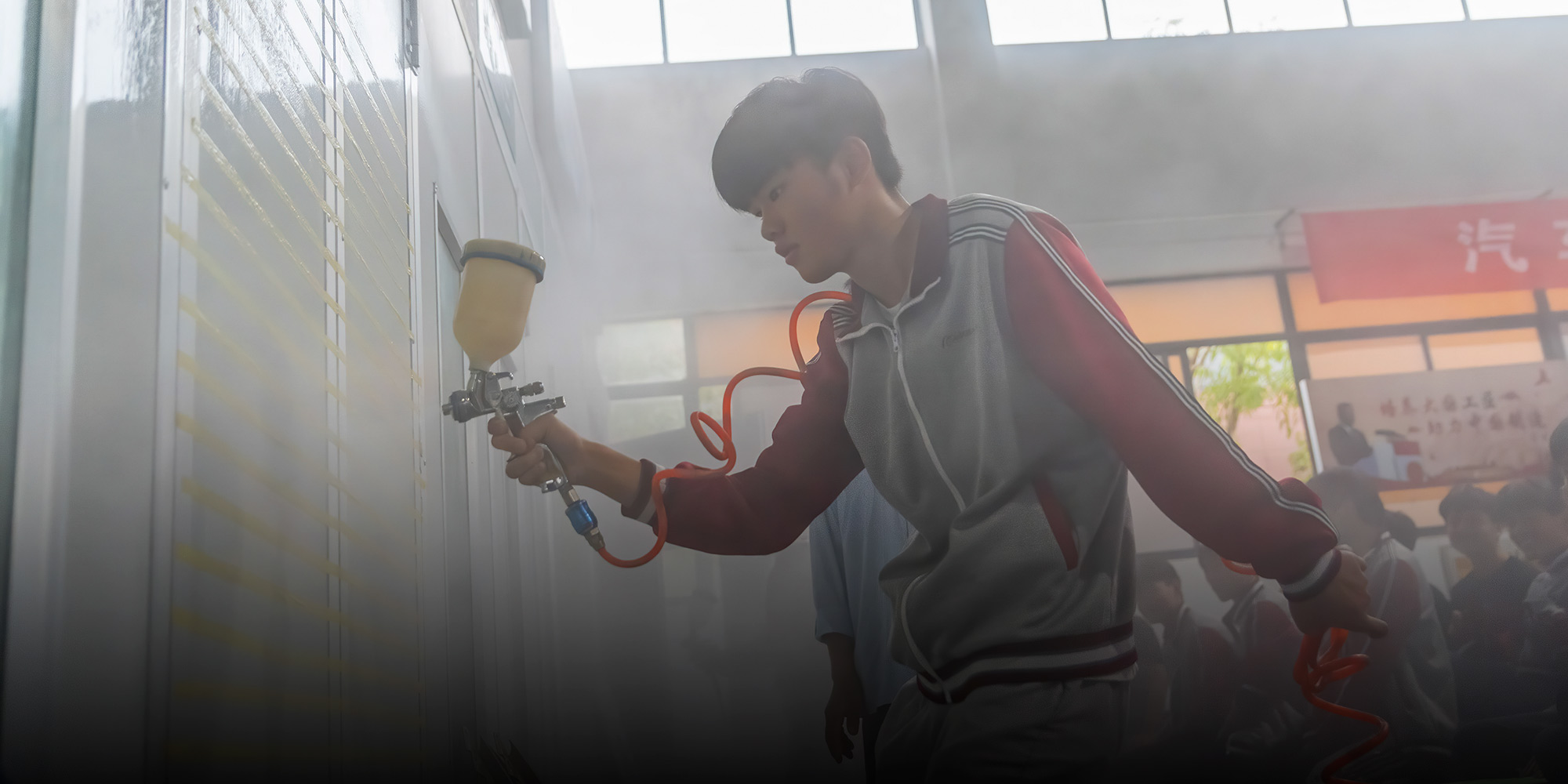

Because the high school entrance exam is designed to fail half the students who take it, tens of millions of teenagers are funneled into China’s vocational education system each year. What they find is an approach to education that places less emphasis on cultivating their knowledge than on ensuring their obedience. To an extent, this serves to prepare vocational students for the requirements of their future careers. After graduating, vocational students generally seek jobs in the manufacturing and service industries. Most employers in these sectors do not expect applicants to possess specialized technical knowledge; instead, they pay more attention to applicants’ personal qualities, such as their willingness to comply with rules, obey orders, and internalize corporate norms.

If you compare the disciplinary requirements of these companies with the rules and regulations enforced at vocational schools, it’s not difficult to see areas of overlap. Vocational schools’ emphasis on following orders rather than exert personal initiative, use of strict schedules, and strict control over students’ personal time all reflect the realities of factory life. Daily military exercises also reinforce these lessons. “If a new student has not undergone military training, they’re not obedient enough,” one teacher told me.

What all this boils down to is dulling students’ sense of autonomy until they become ideal factory workers — not specialists, but cogs who can be switched from one role to another at a moment’s notice to ensure maximum efficiency and productivity.

What’s strange is that teachers, parents, and even some of the students themselves seem content with this system. In part, this is because most Chinese have low expectations for vocational schools and their students. Many parents support “militarized management” because they hope that, if their children learn nothing else, at least they’ll pick up obedience and discipline. “[My child] is still too young to do part-time work,” one parent told me. “We’ll consider that after she’s been at school for a few years. If she can master what she’s studying, that’d be great; but if she can’t, there’ll at least be places that are willing to employ her — she won’t drift through society.”

The administrators and teachers I interviewed also acknowledged that imparting specialized knowledge and skills was not their school’s primary strength. What’s taught at Chinese vocational schools often lags industry standards, meaning it is of little use to students after they graduate. Schools instead emphasize discipline and control. Chatting with teachers, I gradually pieced together their evaluation criteria and requirements for their students. “As soon as the students come in, we tell them that they’re here to be shop floor workers,” one told me. “If they want to do anything else, they should go to another school. Students’ perception of their role is very important: they have to know their place.”

Given the distorted and limited expectations placed on vocational students by society, schools, and even their own families, it’s unsurprising that they tend to develop negative views of themselves. As one student put it, “With my abilities, the highest role I can aspire towards is a senior customer service representative.” Under constant surveillance by teachers who see their primary role as preparing them for a lifetime of drudgery, it’s normal that students would feel unambitious and pessimistic about the future.

Yet even amid all this negativity, students still find ways to carve out spaces of their own. Many of my student interviewees told me that the most enjoyable aspect of their otherwise uninspiring time at vocational school was hanging out with their classmates. Having given up on class, homework, and exams, not to mention any aspirations they may have had to move on to higher education, they attach greater importance to tangible social experiences: hanging out with their peers and having fun together. Through various informal groups and events, students practice forming and maintaining healthy, important relationships that will serve them well in the future.

In recent years, Chinese policymakers and experts have trumpeted vocational education’s potential to help curb the glut of college graduates and keep the country’s manufacturing sector competitive. The current vocational education system is ill-suited to fulfill that potential, but if there is any hope for reform, it should start with a reevaluation of how these schools teach and treat their students.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A vocational school student practises using a spray gun in Feidong County, Anhui province, Oct. 14, 2021. Ruan Xuefeng/People Visual)