In China, People Are Risking Everything for a Box of Ritalin

They came for Jiang Ruiyang on Sept. 2. Ten police officers burst into the factory where he was working in north China’s Shanxi province, told him he was being detained on drugs-related charges, and marched him across the shop floor in handcuffs.

The 25-year-old’s crime: buying a few boxes of Ritalin on the internet.

Similar scenes have played out across China in recent months, as hundreds of people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have become unexpected targets in the country’s war on drugs.

The wave of police raids is the result of a series of policy failures that have left people with ADHD feeling increasingly desperate. For years, China’s health system has made it extremely challenging for adults with the disorder to access vital medication. Many have turned to the black market as a result, but that’s now putting them in the police’s crosshairs.

Stimulants like Ritalin, Concerta, and Adderall are strictly controlled in China, and anyone found buying them illegally can be prosecuted for drug trafficking. Patients like Jiang are effectively being forced to risk a prison sentence to protect their health.

“I still can’t figure out why they did this to me,” says Jiang, who spoke with Sixth Tone using a pseudonym for privacy reasons. “I’m just sick, but they treated me like a criminal.”

Though there’s a widely held assumption in China that ADHD only affects children, millions of Chinese adults have the condition. Lu Zheng, director of clinical psychiatry at the Shanghai Mental Health Center and a specialist who helped draft China’s clinical guidelines for adult ADHD, says the prevalence among Chinese adults is 2.8% — roughly consistent with the global average.

But the epidemic is almost entirely invisible. China’s health system has no designated centers for diagnosing and treating adult ADHD, and Lu estimates only 5% to 10% of Chinese adults with the disorder receive a diagnosis.

“Most ADHD patients have other psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder,” says Lu. “These disorders can make ADHD very hidden. And very few specialists are aware of adult ADHD.”

Failing to treat ADHD only makes the condition more serious. Studies have found that people living with untreated ADHD can suffer lifelong harm: They are more likely to be unemployed, experience addiction and mental health issues, and go to prison.

In Jiang’s case, his untreated ADHD almost killed him. As a child growing up in Shanxi, he often found it difficult to concentrate and stay calm. But it wasn’t until he finished college and started working at a local state-run factory that he realized he may have a mental disorder.

“My parents never took it seriously,” he says. “They believed it was just a problem with me.”

The wake-up call came in November 2018, after Jiang — then aged 22 — was involved in a near-fatal accident at the factory. As he was fixing some faulty equipment on the production line, a mechanical failure occurred. Jiang failed to react, surviving only because his colleagues pulled him to safety.

“I lost my attention at that moment,” says Jiang. “My subconscious was telling me something was wrong … but my brain was receiving too much other information.”

The incident convinced Jiang to consult a psychiatrist, but doing so was easier said than done. In Shanxi, there are only two hospitals able to diagnose and treat ADHD — and neither accept adult patients.

This is far from rare in China. Only a handful of facilities nationwide will help adults with ADHD, and they’re all located in major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing. Very few officially cater to adults; they are overwhelmingly pediatrics wards that make exceptions for some over-14s out of compassion.

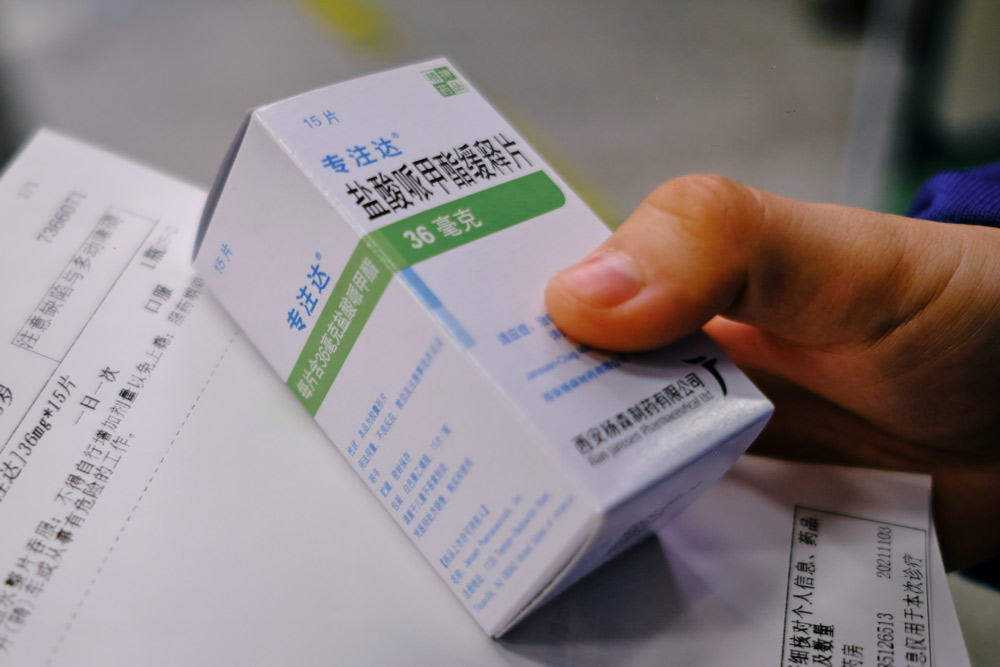

There are several reasons behind the lack of provision, Lu says. Few mental health specialists have experience with adult ADHD, which tends to be a difficult disorder to diagnose. Chinese hospitals, meanwhile, are reluctant to keep methylphenidate — the stimulant used in Ritalin and Concerta — in stock. Use of the drug, which is chemically similar to cocaine, is heavily restricted.

“Methylphenidate can be made use of by criminals,” says Lu. “That’s why even some hospitals that meet the criteria to use the medication are unwilling to: There are large legal risks involved.”

Jiang had to travel to Beijing’s Peking University Sixth Hospital to find a specialist willing to see him. The three-hour train ride from Shanxi was just the start of his problems. Arriving on a freezing winter afternoon, Jiang found there were no appointments available that day — a common issue, as millions of patients travel from all over the country to see doctors in the capital.

He decided to spend a miserable night on the hospital’s doorsteps, to make sure he was first in line the next morning. But even that wasn’t enough: The following day’s appointments had all been booked up, too. Jiang eventually had to buy a ticket from a scalper for several hundred yuan.

After over 24 hours of waiting, Jiang finally saw a specialist and was diagnosed with ADHD. In hindsight, he mainly feels fortunate that the doctor agreed to see him at all.

“It was out of her sense of responsibility that she decided to diagnose me,” says Jiang. “I’m very grateful.”

Access to treatment remains highly insecure and unpredictable for most adults with ADHD. Bai Yichu, a 38-year-old from the eastern city of Hangzhou, visited Hangzhou Seventh People’s Hospital in the hope of receiving a diagnosis in September. But despite the facility having a reputation for helping non-minors with ADHD, the staff there turned her away.

“I visited them because another patient told me they’d just got a diagnosis there in August,” says Bai. “But the doctor said the hospital had standardized its procedures and banned the practice of receiving adults in the pediatrics department.”

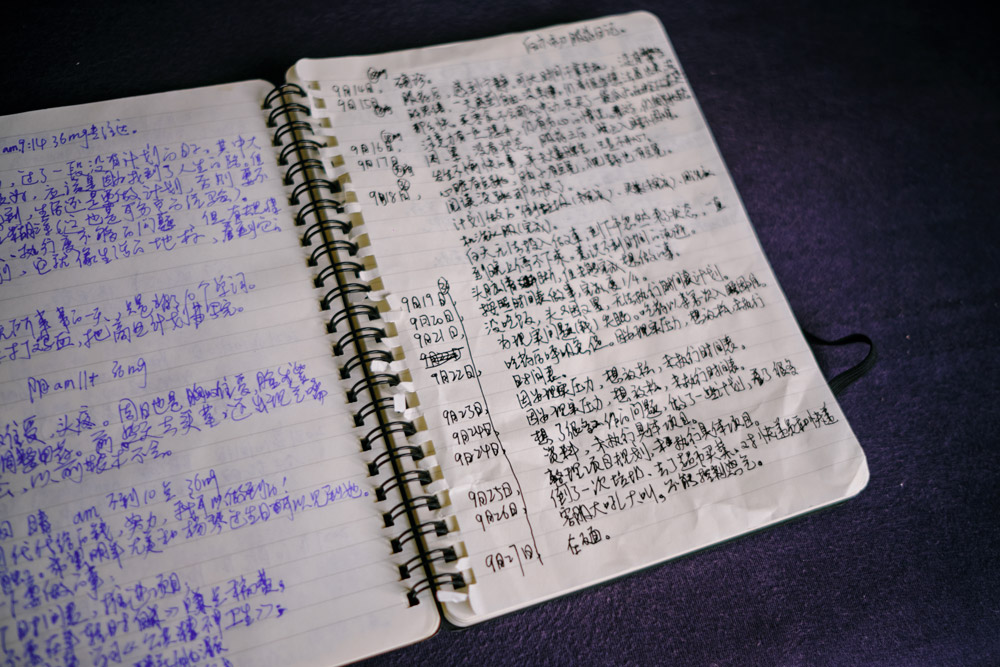

Bai eventually managed to see a mental health specialist at Xinhua Hospital in Shanghai, who diagnosed her with ADHD. But she’s convinced that the disorder has already done irrevocable damage to her life. After nearly two decades of mental health issues — she has also had depression since the age of 20 — Bai finds herself single, jobless, and over 200,000 yuan ($31,300) in debt.

“I’ve likely been affected by the condition (ADHD) for decades,” she says. “I’ve had dozens of jobs, but none of them kept me for more than three months. I’m extremely impulsive — any small thing in life can make me furious or emotional.”

Medication like Ritalin and Concerta can help, but accessing it can also be challenging. Even when patients have been diagnosed with ADHD, they’re not guaranteed to receive a regular prescription due to the insecure nature of being an adult patient in a pediatrics department.

The tight restrictions on methylphenidate make things even more difficult. In April, China’s health authorities finally added adult ADHD to the official list of conditions for which Concerta can be prescribed. (Before then, all prescriptions for adult ADHD patients had technically been illegal.) But even now, doctors can only prescribe two weeks’ worth of pills at a time.

For working-class patients like Jiang, the two-week limit is a huge problem. Jiang had to travel from Shanxi to Beijing twice a month to pick up his medication — a trip that cost him around 1,500 yuan each time.

“Maybe that’s an acceptable sum for wage earners in big cities,” says Jiang. “But for people like me, who earn just under 6,000 yuan a month, it’s a huge expense.”

Jiang did his best to make things work. For several months, he continued to make regular trips to Peking University Sixth Hospital, taking pills only when he was on shift or needed to study to make the packs last longer. But he soon began to feel the arrangement was financially unsustainable.

So when he found out it was possible to buy methylphenidate directly from overseas vendors, Jiang leapt at the opportunity. In a chat group for adults with ADHD, several members said they’d done it, and the pills were just 30 yuan each — around one-third of the cost of buying them in Beijing. From early 2019, he began buying all his medication online.

“I bought the pills via a platform using bitcoin,” says Jiang. “In March, I purchased 30 pills, and then another 120 in May … These are quick-release pills and last for around four hours. I took them when I needed to focus.”

The transactions were illegal, but at the time, Jiang was only vaguely aware that he could face criminal charges for his actions. Chinese patients have begun buying cheap medication for all sorts of conditions from overseas in recent years. When the police raided Jiang’s factory this September, he was shocked.

“I was simply purchasing the drugs online because they’re cheaper,” he says. “I didn’t think that much.”

The arrest has destroyed Jiang’s reputation at work. His colleagues don’t really understand his disorder, but they all saw the police accuse him of taking drugs. They’ve come to their own conclusions.

“Rumors have spread among hundreds of staff here that I’m a drug addict and my mental illness is a result of me taking too many drugs,” says Jiang. “But, despite all the gossip, I have to go to work. Otherwise, how can I afford my medication?”

After showing the police the documents confirming his ADHD diagnosis and taking several drugs tests, Jiang was released on bail. He is now waiting for the authorities to confirm a date for his trial. His main hope is that he avoids going to prison.

“When I told other patients about this experience, some told me the best result would be the police dropping the case, since I can prove I’m truly ill,” says Jiang. “In other cases, some patients were given suspended sentences.”

Lu, the Shanghai Mental Health Center specialist, says several of his patients have encountered similar legal troubles. He’s currently working to set up China’s first dedicated clinic for adult ADHD, which would be a major step toward helping more patients access treatment legally. But it’ll be a long, complex process, and he’s still uncertain when any potential clinic might be able to open, he says.

“We’ll have to set up strict and standardized mechanisms for diagnosis — two or even more specialists will need to diagnose and confirm each case together,” says Lu. “We’ll also need to consult the drug regulators and public security authorities while creating our procedures, to ensure our well-intentioned efforts don’t end in failure.”

Jiang, meanwhile, is struggling to keep his head above water. He has been experiencing severe depression and recently broke up with his girlfriend. But he hasn’t returned to Beijing to ask for more medication yet. He can’t afford any more pills, he says.

“I just want to live well,” says Jiang. “But life seems hopeless.”

Contributions: Zhu Jingyi; editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Bai Yichu takes a dose of Concerta, a stimulant used to treat ADHD, in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, November 2021. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone)