Art for the Countryside’s Sake

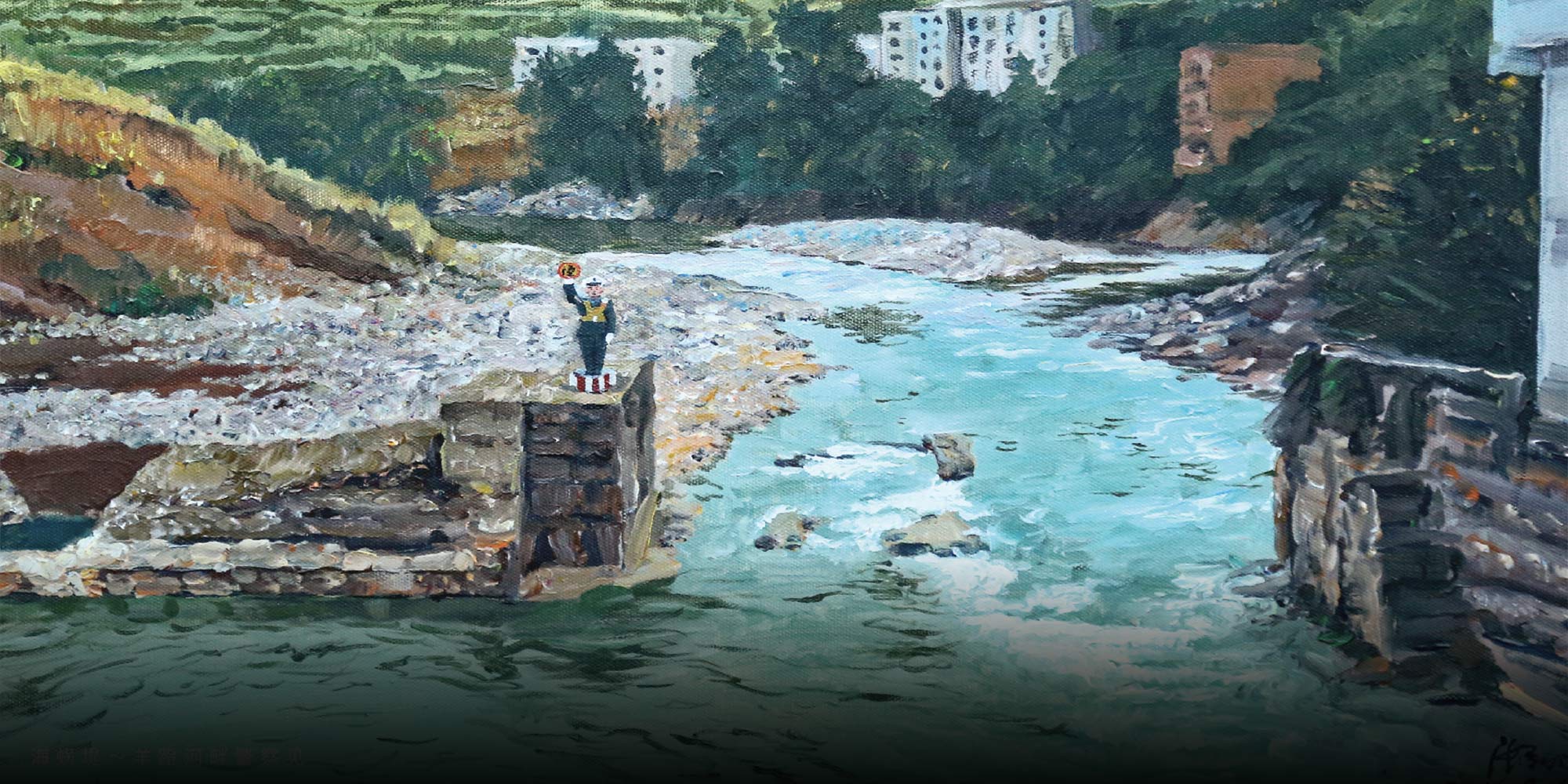

At a recent symposium on the subject of “rural development,” I was given an unusual opportunity: buying an “art package” of local produce from a collective of artists and villagers from Yangdeng, a township in the remote, relatively impoverished southwestern province of Guizhou, as part of the “Yangdeng Muyuan Yellow Peach Art Festival.” A few weeks later, I received a box from the “Yangdeng Art Cooperatives.” Inside was a bundle of peaches and a set of picturesque postcards of the town. Modeled on the famous Song Dynasty series “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang,” they were painted by members of the collective to highlight the region’s most interesting sights — real or imagined.

Modern China is to an extent defined by the dichotomy between urban and rural life. Over the past several decades, people, capital, and land gradually concentrated in economically developed cities, while villages were hollowed out. By the turn of the millennium, this structural conflict was no longer possible to ignore, and Chinese academic and policy circles began to debate how best to address what they termed the “three rural issues”: rural people, rural areas, and agriculture. Since 2004, the first policy document released by the central government every year has been related to rural affairs. More recently, the central authorities have pushed “poverty alleviation,” “rural development,” and “rural revitalization” in an effort to close the gap between city and countryside — and ideally, to push resources from the former into the latter.

The key to successfully redistributing resources lies not in material goods, but in people. Decades of outmigration have left rural areas in dire need of human capital. Only by empowering and educating rural residents can China create a sustainable force for the reconstruction and revitalization of its villages. Given the severity of the problem and the importance the government has attached to fixing it, it’s no surprise that academics, artists, and other intellectuals would seek to play a role in finding the solution.

In 2012, the Chongqing-based artist Jiao Xingtao and a group of young teachers from the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute launched the “Yangdeng Art Cooperatives,” collaborating with locals on a variety of artistic and — more recently — economic development projects.

This experiment calls to mind the early days of the Chinese Communist Party. In the late 1920s and 1930s, many Communist Party members fled the ruling Kuomintang government’s grasp, seeking refuge and establishing new revolutionary bases in remote rural areas. Once there, China’s Communists faced a predicament: In contrast to Western Marxist movements, which originated and developed in industrialized cities, Chinese Marxists were reliant on striking an alliance with relatively uneducated rural people. Only by connecting with and mobilizing this group could they recruit locals to join the revolution and engage in guerrilla warfare.

In response, the early Communist Party leader Qu Qiubai declared that the revolution is first and foremost a cultural one, rather than a political or economic one. On the one hand, urban intellectuals needed to assimilate into the rural majority, thereby undergoing a transition from “bourgeois experts” to “proletarianized intellectuals.” At the same time, they also needed to help emancipate villagers from feudal traditions and rites in order to transform them into better revolutionaries and soldiers.

After Qu Qiubai died in 1935, Mao Zedong took up his ideas and made them his own. In an influential speech at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art, Mao asserted that painting, music, theater, and film all needed to contribute to the ideological reform of villagers and intellectuals alike. Because art could mold new individuals and in turn form new communities, it was a potentially powerful revolutionary force. Mao’s speech inspired a wave of artistic and literary creation, but it also sowed the seeds for the long-term instrumentalization of the arts in China, including a persistent rejection of the concept of “art for art’s sake.”

If we call the early Communist Party’s rural experiences the “old rural development movement,” there’s a case to be made that we’re currently witnessing the rise of a “new rural development movement.” As with its antecedent, this rural development movement is fundamentally concerned with forging ties between villagers and educated urbanites. But where the old movement sought to transform villagers into revolutionaries and soldiers, today’s movement aims to include villagers in the economic systems of modern cities and markets. And while the old movement required cultural creatives from the city to undergo “personal reform” by abandoning the ideology of the petty bourgeoisie before helping rural residents, today’s creatives approach their “development” projects from the perspective of Western concepts, whether in contemporary art or aid work. One movement followed the path of proletarian revolution; the other adhered to the logic of the market economy.

The current generation of artists engaged in rural development don’t always enjoy having this pointed out to them. In a speech, Jiao Xingtao, the founder of the Yangdeng Art Cooperatives, described his work with a string of negative statements: “It’s not about sampling local cultures, it’s not about experiencing local lifestyles, it’s not rural construction in a sociological sense; it’s not cultural philanthropy or artistic charity; it’s not about bringing contemporary art to the villages — there are no pre-defined objectives or plans.”

This is typical of contemporary artists: to reject definitions, to reject the instrumentalization of art, and to refuse to acknowledge their work is in service of some grand narrative. Although the Yangdeng artists used the term “cooperatives” in a nod to the experiences of the socialist revolution, they are more like a small interest group composed of disparate parts, some urban, some rural. Locals’ attitude toward their work is mixed — there are happy participants, as well as critics and indifferent bystanders.

This year, however, the cooperatives underwent a comparatively major transformation, as its artist members founded a new social enterprise: the Chongqing Yangdeng Culture Communication Company. Its urban members began to realize that they could not stop at disinterested aesthetic practice, but also had to help villagers transform the culture and art they were producing into concrete economic benefits. It was this new enterprise that sold me that “art package” of locally grown peaches. In addition to the cultural ties they’ve formed over the past decade, the relationship between urban artists and local villagers is now taking on a commercial veneer.

Again, there is nothing particularly new about this. In “community supported agriculture,” which first cropped up in countries around the West in the 1960s and 1970s, urban dwellers began to forge ecological agriculture partnerships with rural farmers that allowed them to buy fresh and organic food from local producers and have it shipped to them in urban areas. In Yangdeng, artists have teamed up with business interests to promote cultural tourism in the region.

For all the importance placed on “art for art’s sake,” it is generally a privilege reserved for members of the middle class, who are in a better position to spend time and money on cultural activities. Given the deeply ingrained disparities between rural and urban China, it is perhaps unrealistic to expect middle-class urban artists and working-class villagers to share the same set of artistic ideals. Perhaps endowing art with social and economic functions is a more viable approach.

Still, the commercialization of the Yangdeng Art Cooperatives was probably not on anybody’s wish list back in 2012. Did the artists betray their original purpose? Or was it simply a way for them to balance their artistic ventures with the needs of Yangdeng’s economy and people? I lean toward the latter explanation. Art can and sometimes should be repurposed for utilitarian ends, whether that’s boosting tourism or selling produce. There’s no reason to oppose the Yangdeng Art Cooperatives’ commercialization, provided it’s conducted in a professional manner. Urban artists have long tended to misunderstand what rural residents really want, which is first and foremost economic growth and better material conditions, not abstract artistic ideas.

Of course, there is a paradox here: Art must retain a certain authenticity and fidelity; otherwise, it risks losing its charm and appeal. But in order to achieve the freedom needed to pursue this authenticity, art inevitably has to be incorporated into the growth of rural economies. Only after villagers’ economic prospects improve and their basic needs are met will artists enjoy greater space for artistic expression.

All this is to say that we must lay the economic and social foundations of a better countryside through commercial projects before organizations like the Yangdeng Art Cooperatives can reach their full potential. Sometimes, you have to instrumentalize art to de-instrumentalize it.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

(Header image: A postcard showing the banks of Yangdeng River. The image was painted by artist Zhang Xiang in 2016 as part of a project organized by the Yangdeng Art Cooperatives. Courtesy of Yangdeng Art Cooperatives)