How to Live for Free in Beijing: An Artist’s Guide

BEIJING — Like many art students, Zou Yaqi often worried she’d be unable to afford to live in Beijing after graduation. So, earlier this year, she decided to set herself a daunting challenge: Survive in the city for three weeks without spending a single yuan.

It turned out to be a piece of cake.

The 23-year-old spent most of May living the high life: gorging on buffets in VIP lounges, sipping wine at exclusive events, and sleeping on plush sofas in the lobbies of five-star hotels. She ended up sticking to her zero-yuan budget with ease.

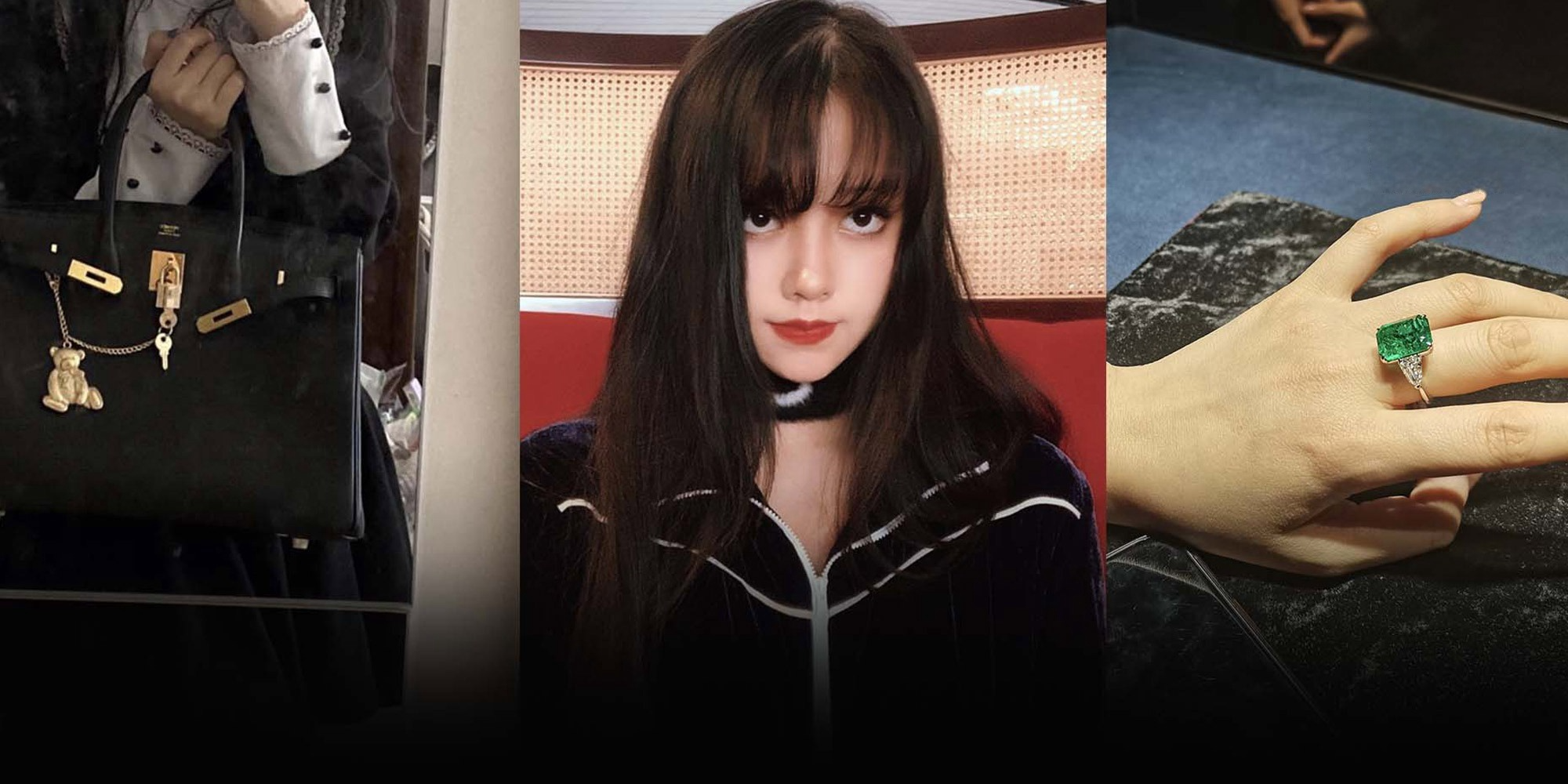

The secrets to her success? A fake Hermès handbag, bright red lipstick, and a velour designer tracksuit — all of which helped Zou pose as a member of China’s wealthy social elite. She found that when she was disguised as a mingyuan — or “socialite” — businesses would let her exploit their hospitality without question.

“Though I’m poor, I was able to enter the world of the rich and get their free stuff,” Zou tells Sixth Tone. “I wanted to break the rules.”

The experiment — which Zou documented and later turned into a performance art project — has since become one of China’s most talked-about artworks of 2021. But it has also thrust the artist into a heated — and, at times, ugly — debate about class and privilege, highlighting the deep rifts that have opened up in Chinese society.

China’s rising wealth inequality has become a hot-button issue in recent years. The top 20% of earners in Chinese cities now have five times more per capita disposable income than the bottom 20% on average, with the gap nearly doubling since 2000.

Public attention has focused on the wealth divide even more in 2021, as the Chinese government has made tackling the issue one of its top policy priorities. In the summer, authorities vowed to “adjust” excessively high incomes and force the rich to “give back to society.”

So when Zou presented her project at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts in June, it quickly went viral on Chinese social media. At one point, the artist even became a trending topic on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like microblogging platform. But the response to her stunt has been far from universally positive.

While Zou said her stunt was intended as a criticism of capitalism and consumerism, many critics have accused her of being unaware of her own privilege. Her experiences as a student at one of China’s elite arts colleges, the theory goes, allowed her to pass as a socialite with ease.

“What enables her to accomplish her performance art is precisely her class,” wrote one user on Weibo. “Everything — her makeup, choice of props, successful repartee in each place, and the individual image she presented — come from the invisible accumulation (of cultural capital) prior to the experiment.”

The artist, however, insists that such criticism misses the point. Though she won a place at a fancy Beijing school, she grew up in a small city in central China’s Hunan province. It was the dizzying transition between these two worlds that inspired her to create the project.

When Zou first visited Beijing to attend an art exam cram school, the then-17-year-old recalls being amazed by the luxury inside the glitzy shopping malls in the central business district.

“The place where I was staying wasn’t even as nice as the toilets (in the malls),” Zou says.

After she began studying at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, this feeling grew. Zou says she became increasingly fascinated by the excess on display at the campus. During exhibition openings, hungry students like herself would “madly” eat the caviar-topped canapes on offer, while other well-heeled visitors ignored them.

“Those elegant people barely ate them, and they’d go to waste,” Zou says. “We were stuffing ourselves till we were full, like we were at a free buffet.”

Zou coined a term to describe this phenomenon: “excessive goods.” An “excessive good” could be anything that is given to the wealthy for free, but is inaccessible to the non-wealthy. A complimentary snack at a swanky bar. A free gift at a luxury store. A bottle of wine at an invitation-only dinner.

To Zou, these “excessive goods” were a potent symbol of the wealth gap. They were seemingly everywhere, yet the capital’s high-rollers barely noticed them. Often, they ended up being thrown away.

“It’s very interesting how such free ‘excessive goods’ are distributed: They’re often given to people who seem to already have plenty,” Zou wrote on Weibo.

Haunted by financial worries and unsure how she would make rent in Beijing after graduation, Zou began to wonder: Could a person simply live off the “excessive goods” that she saw all around her every day?

The plan for her 21-day experiment crystallized during her final year at college. It wasn’t a practical solution to her money problems, but an attempt to make people think. By passing herself off as a mingyuan, infiltrating Beijing’s posh hangouts and living entirely off the freebies they provided, Zou aimed to highlight how Chinese society had become increasingly divided under capitalism.

In January, Zou started making preparations. She visited dozens of venues — from supermarkets, to bars and hotels — to find out where she might find free food and accommodation. She slowly developed a rough itinerary of places to hit during her 21 days on the streets.

Then, the artist moved on to the next stage: learning how to look like a member of the Chinese elite. She spent hours on social platforms Xiaohongshu and Douyin, studying how mingyuan dress, wear their makeup, and behave. She prepared an entire new outfit to make her disguise more convincing, including a fake luxury handbag, a knock-off diamond ring, a designer velour tracksuit, and a bright red lipstick .

“I’m more cautious and casual in daily life, but I had to present an elegant, haughty, and self-confident image,” says Zou.

By May 1, Zou was ready. The experiment began.

Her first stop was an airport VIP lounge. Armed with a forged entry pass — the kind that Chinese banks, travel apps, and airlines sometimes give as a perk to regular customers — Zou strode up to the staff at the entrance. To her relief, they glanced at the slip of paper and let her inside without question.

“I was very nervous and thought I’d be driven out the next second,” Zou says. “But nothing happened.”

The pass was only valid for three hours, but Zou ended up staying in the lounge for three days, sleeping on a semi-circular red sofa and eating “as much food as possible” from the three daily buffets. The staff didn’t seem to care whether guests overstayed their welcome, she says.

On her first day, Zou also headed to a Gucci store downstairs, where she convinced the staff to give her a free bag bearing the brand’s logo. The paper bag proved doubly useful: It helped Zou steal a large amount of bread from the VIP lounge and made her look even more like a regular buyer of luxury goods.

When Zou later walked into a nearby Louis Vuitton store with her fake Hermès and Gucci shopping bag, the two service assistants abandoned their other customers to greet her. They showed her a 6,000-yuan handbag and even offered her an invitation to an LV exhibition.

“I assume they wouldn’t say this to ordinary guests,” says Zou, who has never bought an LV bag. “They treated me like a regular customer with buying power.”

After a few days of the experiment, Zou recalls no longer feeling so nervous. Pretending to be a socialite had become second nature, she says.

“I was constantly playing the role all day,” says Zou. “I soon got used to the contradiction: My body was dirty and slimy, but I was seen as a beautiful and rich woman by others.”

For the second half of the experiment, Zou left the airport and moved to Dongcheng District — a prosperous part of central Beijing filled with bars, art galleries, and five-star hotels.

At a high-end hotel, she made up a fake name and room number to register at the front desk, which allowed her to access the public bathrooms. For the first time in days, she enjoyed a comfortable shower, and even used the sauna and steam room.

By now, Zou was becoming increasingly brazen. When she returned to use the bathrooms, the fake names she used included Liu Bei — the ancient Chinese warlord — and Rin Tohsaka, her favorite Japanese cartoon character.

The latter one raised the suspicions of the customer service assistants, who said there were no bookings under that name. But Zou was able to reassure them by saying she had just checked out and would be leaving soon. Again, she was allowed in.

“I was already numb and didn’t panic at the time,” says Zou. “I just thought, ‘Finally, there’s a conflict.’”

One night, Zou attended an auction using an invitation passed to her by a friend. Between stuffing herself with goose liver pate and white chocolate desserts, she tried on several of the auction lots — fine jewelry that later sold for millions of yuan. She recalls slipping a beautiful emerald ring onto her finger and comparing it with the 18-yuan glass diamond one on her other hand.

“That moment really struck me,” says Zou. “They looked so similar at first glance, but the value was so different.”

Zou’s experiment came to an end in the lobby of yet another high-end Beijing hotel. She spent her final night sleeping on an orange sofa, surrounded by an artificial bamboo grove. She recalls feeling like the two security guards who stood nearby were there to keep her safe.

The following month, the student presented video clips and a collection of objects she’d gathered during the experiment — including the Gucci bag and hunks of stale bread — at her graduation exhibition. She wasn’t shocked when Chinese media picked up her stunt; she’d expected her project to resonate with the public.

But Zou was caught off-guard when the story began to focus on her own background, and social media commenters started to describe her as a mingyuan in a different — and much less pleasant — sense.

The word mingyuan has become ubiquitous in Chinese media in recent months, and the meaning of the word has begun to morph. No longer simply a term to describe true socialites, it has acquired classist and sexist connotations. Increasingly, it’s used as a derogatory term to describe women who flaunt fake wealth in order to get attention.

The criticism has frustrated Zou. She only used the word mingyuan once in the introduction to her project, but says some online media jumped on the buzzword and hyped up her story to generate traffic. She insists that she’s neither a member of the elite, nor a wannabe online celebrity, but a member of “the proletariat” who undertook her project with sincere artistic intentions.

Though her family are hardly poor, they’re also far from wealthy, Zou says. Her parents earn a “modest income” and provided her with a 3,500-yuan monthly allowance during university.

As a student, Zou was able to earn extra income from working part-time as an actor and model, making around 800 yuan a day on average. But she stresses that she has “zero assets” and buys her clothes from charity shops and Pinduoduo — an e-commerce platform famous for its cheap products.

Now, Zou is determined to move on. In some ways, the criticism is simply a reflection of how hotly discussed her project has been, she says. And it has already helped her win a contract with an art agency, which has allowed the fresh graduate to start her career as a professional artist.

In late October, Zou’s latest work — a video project about orientalism — went on display at a gallery in Tokyo. She plans to continue creating socially engaged art in the future, she says. If the critics carry on complaining, so be it.

“Artworks are bound to be misunderstood as they spread,” says Zou. “People will hear what they want to hear, and those interpreting the work will explain it in a way their audience wants to hear.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: A collage of photos showing Zou Yaqi (center) pretending to be a socialite. Courtesy of Zou)