Unplug and Play: A Mother’s Desperate Plea to Her Kids

One day during summer vacation, seven-year-old Guoguo started crying. Again.

Mouth wide open, he screamed at the top of his lungs, tears rolling down his cheeks, his face contorted. It was the middle of the day, and his shrill cries echoed loud across a six-story residential building in a village near Taiyuan, capital of the northern Shanxi province.

But neighbors were unperturbed — for them, such a ruckus was routine. They knew well why Guoguo was throwing a tantrum: His parents had taken away the smartphone.

Guoguo is from a working class family; his mother, Fang, 35, is a stay-at-home mom while his father, Liang, is a truck driver. He has a twin sister named Tangtang and a 12-year-old sister named Panpan.

Such is the popularity of short videos on mobile apps over the last few years that Fang says the twins became obsessed with smartphones even before learning to read. Guoguo can’t type yet but has worked out using voice input instead.

Across China, it is a dilemma that plagues young parents. A simple internet search for “What to do if your child is addicted to cellphones?” yields millions of results.

The sheer number is symptomatic of the anxiety smartphones cause. With China encouraging couples to have more children, more young parents are now struggling to cope.

Fang is no exception. She asserts that all her children were exposed to omnipresent cellphones while still infants. She says, “They have become addicted.”

For years now, Fang has waged a long, hard, and lonely battle against smartphones, making personal sacrifices to balance career and family along the way.

Her experience offers a glimpse into the lengths parents are willing to go to bring up multiple children in the digital age.

Battle of the ages

Whenever her twins aren’t heard around the house, Fang knows for certain that they have “appropriated” a grown-up’s cellphone. Locked in a perpetual battle of wits with her children, she often hides her phone and periodically changes the password. Sometimes, Fang has been unable to find it herself.

The day before Guoguo’s outburst, Fang dropped him off at her parents’ home since she had to attend a wedding. Before leaving, she promised to buy him a new toy gun and warned her father not to let Guoguo play with his phone.

Her father promised to take his grandson to the park, and then let him watch some TV before bed.

When he got up at 5 a.m. the next day, Fang’s father found his grandson on the sofa in the living room. He was huddled in a corner, swiping the phone with a blank expression, completely oblivious to what his grandfather was saying.

Somehow, Guoguo had managed to sneak past him, unplug his phone from its charger, and then crack the password.

Guoguo’s grandfather took the phone away and demanded to know how long he’d been using it. Guoguo sat there startled, before saying it was sometime after 4 a.m. But the phone was so hot that he obviously had it for much longer.

Fang was furious when she found out. When her husband Liang got home, he slapped Guoguo on the back of his head and kicked him in the behind. He sent his errant son to his room to think about what he’d done, and told him he would not see a phone until he finished his summer break homework.

That firm rebuke triggered Guoguo’s tantrum.

Most in the family believe cellphones have “poisoned” Guoguo. Such is his obsession that when asked in school about his three favorite things, he replied: “First, is playing on cellphones and second, is watching others play on cellphones.”

He racked his brain for a third but couldn’t come up with an answer. Prompted by the teacher, he reluctantly said that he likes learning.

Fang’s concerns about Guoguo’s twin, Tangtang, are almost identical.

When Tangtang was an infant, Fang showed her some early education cartoons, which she says helped her younger daughter learn several English words.

Those days, Tangtang was almost perfect. “She was polite and always said thank you when she was given something,” says Fang.

Ever since kindergarten, Tangtang has loved frilly dresses, hair braids, nail polish, and shiny bags, and would spend half an hour every day looking in the mirror. Soon, she began devouring videos of Barbie dolls, toy home decorations, DIY clay objects, and toy tutorials.

Initially, Fang thought this was normal for a girl. Soon, however, she noticed more: Tangtang would pretend the lid of a water bottle was face powder and often stood on two blocks imagining they were high heels.

Eventually, Fang tracked the source — her younger daughter was binge-watching short videos about makeup and manicures on her father’s phone.

Fang worried that such an early obsession about her looks would affect her schoolwork and decided to speak to her about it. Tangtang dismissed her mother and asserted that she wanted to become a beauty blogger.

One birthday, an aunt gave Tangtang a gift but she didn’t rush to open it. Instead, she borrowed her father’s phone to record an unboxing video. It only steeled her parents’ resolve to to guard their phones more closely.

This year, Tangtang starts elementary school, and Fang is anxious that she might develop an interest in dating too early.

As early as kindergarten, Tanngtang drew attention from many boys. According to her teacher, two boys once even fought over who would hold her hand while her brother Guoguo cheered them on.

A mother’s sacrifice

For the current generation of young parents — both urban and rural — the battle against electronic devices begins the moment children are born.

Fang’s children often got gadgets as gifts from relatives, including smart reading pens, phone watches, and electronic writing tablets. But soon, they lost interest in such devices.

But the “big cellphone” — an iPad — is different. From the early days of the BabyBus and Panda Literacy apps, all the way up to Game for Peace and short video apps like Douyin and Kuaishou, the internet promised endless entertainment.

Fang’s children always seemed to crack the iPad passwords with ease, so she resorted to either hiding the tablet or telling them that she had lent it to someone for online lessons. She could only hope this curbed their addiction.

But the problems persisted. Before Fang’s eldest daughter Panpan was even five, she required an examination at the Shanxi Eye Hospital because her eyes were always red.

Doctors discovered she had relatively advanced strabismus — a disorder in which the eyes don’t look in the same direction at the same time. Fang and her husband were stunned. In three generations, no one in their families were nearsighted but their young daughter already required glasses.

Fang believes their obsession with phones began when she went back to work after her children were old enough. Those days, she often left them with her in-laws.

Their house is on a busy truck-laden road, and the front yard is bumpy and uneven. Worried the children might hurt themselves playing outside, their grandparents gave them a phone to play with. It was also the only way to keep them quiet.

Most days, their grandfather sat on a bench with a child on each leg, all three watching trashy, short videos with over-the-top acting, as well as those about pancakes, makeup, and building furniture.

The many educational books, toys, and a tablet Fang had bought the children just gathered dust since their paternal grandparents knew little about operating them.

When Fang realized her children spent most of their time staring at screens, her first reaction was to confront her in-laws. But she realized this would only complicate her relationship with them.

Both Fang’s and her husband’s parents had little schooling. Their idea of childcare was simple. Says Fang: “If they’re not crying, causing trouble, or getting hurt, then everything is fine.”

Determined to bring her children up the right way, Fang made a big decision: She quit her accounting job to discipline her children herself.

That’s when she noticed just how much cellphones had affected a generation of children in rural Taiyuan. They don’t jump rope in the yard or chase each other around in the village square, nor do they play games like cat’s cradle or hopscotch.

After their daily physical education class, they just stand around in the shade and discuss what’s on their phones.

Fang is not alone in her distress — most parents in Taiyuan share such anxieties.

Fang’s 15-year-old nephew Zhibin rarely speaks with his parents. When his mother once peeked into his phone, she discovered he and several other boys had a WeChat group where they discussed campus romances, their teachers’ cars, video game news, and even how to ask parents for money.

The two mothers shrug helplessly when they talk, often remembering the simplicity of their own childhood. With so many temptations, it’s now hard to predict how their children will turn out.

Balancing act

In 2016, about two years after she started work again, Fang quit her job. At the time, it was seven years into her marriage. Until then, she did her best to juggle work and her family. But her decision to stay at home upset the balance on which she had worked so hard.

Fang and Liang married out of love. Originally junior high school classmates, they lost touch after graduation but met again a few years later. At the time, Fang was studying at a finance junior college and Liang was a truck driver.

Though her parents staunchly opposed the marriage, Fang was deeply in love. She recalls her mother telling her: “When things get hard in the future, don’t come crying to us about it.”

Fang’s in-laws are farmers with meagre savings. Since Liang didn’t have the money to buy a house after the wedding, they could only add new rooms to his parents’ old courtyard home before moving in with them.

Liang’s family contributed just 30,000 yuan ($4,700) for the wedding and they even borrowed more than 100,000 yuan, which took Fang and Liang two years to pay back.

Her mother’s warning rang loud soon after Panpan, Fang’s first child, was born. Liang mostly played cards and spent his free time drinking with friends rather than helping Fang with childcare. With her father-in-law always busy on the farm and her mother-in-law’s attitude towards upbringing not up to Fang’s standards, she was forced to bring up Panpan alone.

Moreover, in the countryside, water and electricity were erratic, which meant she had to wash the diapers by hand in the yard. Only when Panpan started kindergarten and Fang went back to work did she feel at peace.

Six months later, though, she was pregnant again.

At the time, Fang contemplated an abortion but decided against it when told she was expecting twins. Unwilling to give them up, she quit her reasonably well-paying job instead. When the twins arrived, she was the envy of the village, but she recalls feeling despondent and says she often cried.

As the children got older, Fang summoned up the courage to return to work. Just one month later, she discovered her son’s cellphone addiction and was forced to cut her work short again. In the past, she had been awarded the title of “exemplary worker” at her accounting company two years in a row.

To keep her children off cellphones, she has tried distracting them by taking them out to play and even tried teaching them to use cellphones to learn something useful.

So far, nothing has worked. On the contrary, she’s now convinced smartphones only strain parent-child relationships.

Once, when a large amusement park opened in Taiyuan, Tangtang and Guoguo pestered Fang about going. Since fall was around the corner, Fang was afraid they’d catch a cold, and made up an excuse that it wasn’t open yet and that she’d take them next summer.

Her son saw through the ruse immediately. He told her: “On Douyin, they said it opened ages ago — I’ve seen people playing there!”

Countering cellphone addiction involves the whole family. Here, Fang says, her husband Liang fell short.

Fang doesn’t allow the children to play with cellphones or watch TV before finishing their homework. But Liang, on returning home, often sprawls on the sofa to start watching short videos.

The children listen in while doing their homework, and can even recite scenes from some viral videos he’s watched. Despite her repeated warnings, Liang is yet to take the issue seriously, which has led to several arguments.

Fang remembers the time she finally snapped. She was cooking dinner when Guoguo snatched the cellphone from his twin sister. A fight ensued and both began to cry.

When Fang looked at their homework, they had written fewer than 10 words in one hour. Meanwhile, Panpan, her eldest daughter, had closed the door to her room and didn’t want to talk with her. And Liang, who had returned from work, was fast asleep.

After dealing with the twins, Fang returned to the kitchen, only to find the rice had burnt.

Though a full-time mother, Fang also runs her own WeChat store, earning 2,000-3,000 yuan every month to help support the family. She also takes care of the housework and discipline.

But that night, despair crept in. She broke down, saying that she understood “why some women jump off a building with their child.”

Give and take

As her campaign against her childrens’ cellphone obsession continues into this year, Fang has changed tack. Realizing it was unrealistic to completely isolate her children from the ubiquitous smartphones, she tried turning the phone into a tool for discipline.

It affected Guoguo the most.

He was often naughty — he’s broken a sofa at home from jumping on it, smashed a fish tank, and even provoked a big dog until it bit him. When given medicine, he cries and refuses to take any. But when told he could play with the phone, he immediately becomes docile.

Tangtang is much the same. Fang says she often lazed around while doing her homework, but would suddenly concentrate and finish her work when promised 10 minutes of cartoons.

Panpan, however, is an outlier. After the COVID-19 pandemic, Fang had to set up a cellphone for Panpan, currently in sixth grade, so she could attend online classes and submit assignments.

According to Fang, Panpan uses the phone to look up words in the dictionary, set alarms, use the calculator, and check things she doesn’t understand. For Fang, she’s a model student — her scores are among the highest in her class.

But while locked in her room, Fang has overheard Panpan using profanities while chatting with her classmates. She says all children have to go through this phase, and that there’s always a limit to how much parents can manage.

Amid her many troubles, Fang says there are still moments of bliss, like when her children loudly declare, “I love you.”

Though they don’t study particularly hard, their grades aren’t that bad. “And while Liang might not help with the housework, he does hand over all the money he earns, and has worked harder after the twins were born,” she says.

Sometimes, Fang feels Guoguo’s phone habits are not all bad. He likes movie explainer videos, especially superhero and sci-fi movies. To test him, his aunt once asked him to tell her the whole story of one particular superhero movie — he recounted everything without missing a single point.

The aunt suggested Fang sign Guoguo up for a speaking class, believing it might help him become a talk show host or something similar in the future. To Fang’s surprise, Guoguo, who usually struggled to concentrate on anything for more than a few minutes, showed rare focus while performing.

A few months ago, Guoguo even hosted the Children’s Day event at his school. While practicing, he returned home every day to rehearse his long lines — the focus helped keep him calm.

Sometimes, Fang wonders whether she invested enough time or patience in bringing up her children.

“In the end, the needs of my children are primarily emotional,” she says. With little support from parents, smartphones are arguably the cheapest source of happiness.

Even in Taiyuan, a second-tier city with lower levels of consumption, there is still significant economic pressure on a three-child family. Fang’s eldest daughter has dance and piano lessons; her youngest daughter takes art classes and for a while dance classes too; and her son attends taekwondo, calligraphy, and speaking classes.

Every year, classes for all three children cost nearly 100,000 yuan ($16,000).

Like most parents, Fang wants her children to travel and get in touch with nature, but her resources are limited.

For example, a long-promised trip to Disneyland in Shanghai never materialized since the couple spent most of their time and money bringing up the children.

Asked whether Fang feels she can control her children’s smartphone mania, she says she already feels powerless.

The question of how to discipline children today — when cellphones are so integral to life — is a societal dilemma. In this generation, parents like Fang are trying to strike that difficult balance between openness and control, concern and understanding.

A version of this article originally appeared in Code for Life. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Xue Yongle and Apurva.

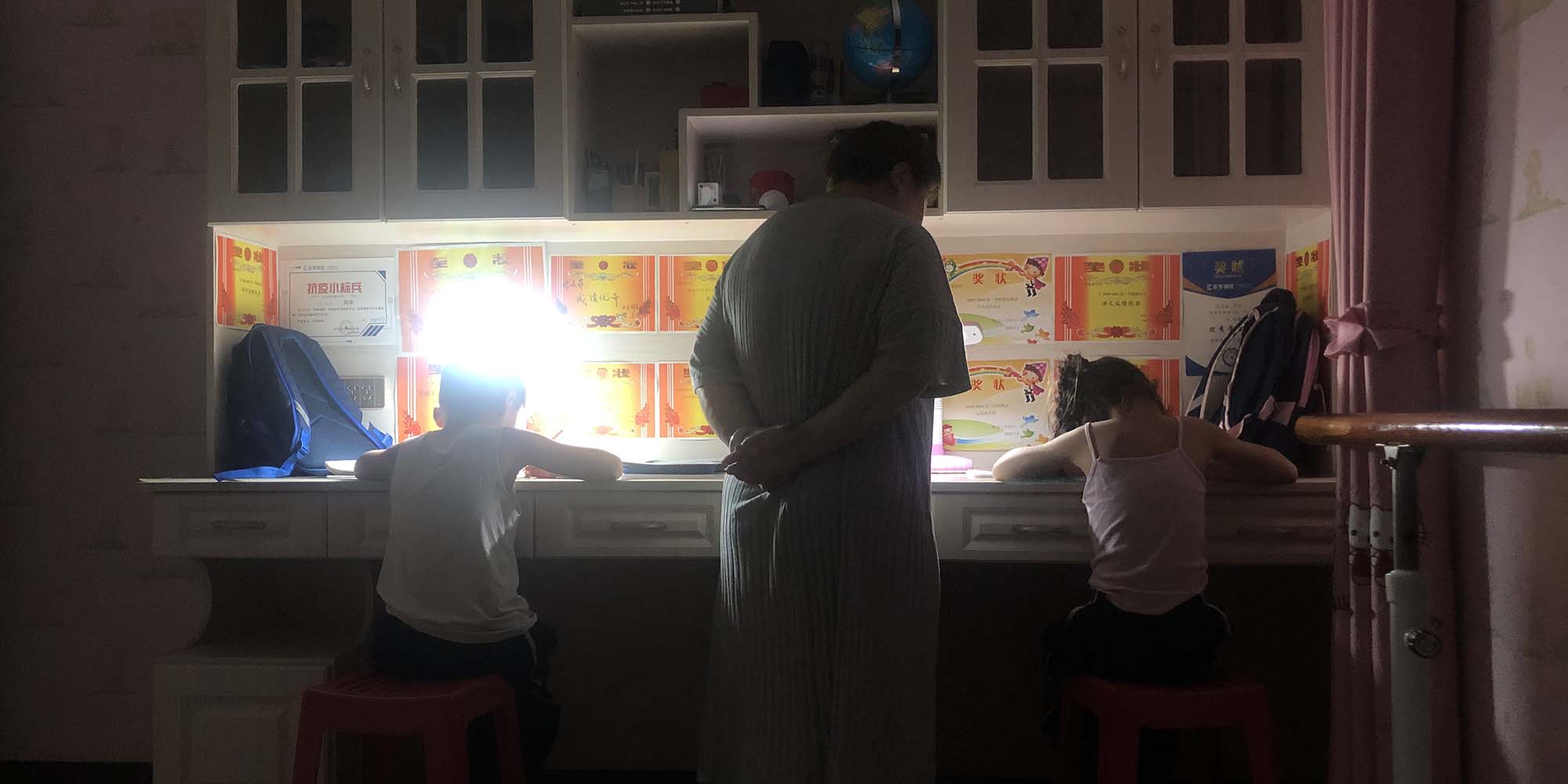

(Header image: Fang supervises her children as they do their homework. Courtesy of Li Kangti)