Drinks with the Grand Historian: Remembering Jonathan D. Spence

On Dec. 25, 2021, the eminent historian Jonathan D. Spence died at the age of 85. One of the most influential sinologists of his generation, Spence was the author of 14 books on Chinese history, including classics like “The Search for Modern China” and “The Death of Woman Wang.” His work showcased a talent for crafting vivid narratives and historical reconstructions from small details, earning him readers far beyond the confines of academic history. As the MacArthur Foundation put it when it awarded Spence one of its prestigious fellowships in 1988: “His work integrates literary storytelling with original historical perspectives, creating a detailed and colorful narrative that seems to allow historical figures to speak with their own voices.”

Spence wasn’t just an academic; he was also an extraordinarily kind and generous mentor to generations of Chinese scholars. For 13 years, from 2005 to 2017, he — together with his wife, fellow historian Annping Chin — organized and oversaw an exchange program between Peking University and Yale University that brought dozens of doctoral students from Beijing to New Haven. It was the pair’s hard work that kept the program running, and they took it upon themselves to welcome visiting scholars not just into New Haven’s research circles, but also into their lives.

I first met Professor Spence through this exchange program. Arriving in the United States in January 2013, I found myself stuck in customs for hours longer than I anticipated. By the time I reached New Haven, it was already 9:30 p.m. I can still picture our meeting clearly: my classmate Du Hua and I were standing at the entrance to Yale’s Hall of Graduate Studies on York Street. On a cold, rainy night, we looked out onto the street to see two figures emerging from the orange glow of the streetlamps. It was Spence and Chin, who had come to greet us.

Many people have commented on Spence’s resemblance to Sean Connery. They’re not wrong: He was tall and straight-backed, with deep-set eyes and a full beard. Spence didn’t have an umbrella, and his white hair was slightly wet by the time he reached us. Smiling, he looked at us warmly and said: “Welcome to Yale.” Chin then gestured toward the bamboo basket her husband was carrying in his left hand and said: “Are you hungry? There’s dinner prepared for you in the basket.” The couple accompanied us up to our dorm rooms, which were completely empty. Chin shook her head at the sight and sighed. Turning to her husband, she said, “Jonathan, we must remember to bring them some quilts and pillows tomorrow.” Spence nodded and smiled. I’d heard the couple were extremely kind to young Chinese scholars, but to personally experience this warmth and care was extremely moving.

Over the next six months, Spence and Chin invited Du and me to their home for dinner on several occasions. They lived in West Haven, near to New Haven and not far from Yale’s campus, where they had a lovely garden. Chin would cook paella, while Spence would mix cocktails of all different colors. They were close; they even shared a cellphone. The way I saw it, Spence seemed to enjoy keeping the modern world at arm’s length.

Near the end of my studies at Yale, I even had the unexpected privilege of formally interviewing Professor Spence. In May 2013, the Chinese edition of Esquire magazine contacted me and Du about interviewing Spence for a special issue it was running on academics. By the time the interview took place that June, Du had already left Yale and returned to Beijing, so I met with Spence at his home while Du joined via Skype. Spence was in good spirits as we chatted, his wife by his side.

When I asked which era in China he would most like to have lived in, Spence said that he’d like to meet the great Western Han Dynasty (202 BC - AD 9) historian Sima Qian. That was not necessarily surprising: Spence’s Chinese name — Shi Jingqian — means “looking up to Sima Qian.”

“He (Sima Qian) really understood how to construct stories and how to make them have a lasting impact,” Spence explained. He even described to me how he imagined meeting the historian would have gone: “We would have greeted each other and poured each other some wine. When we parted, Sima Qian would have said to me, ‘Hey, buddy. Nice to meet you, we should do this again!’”

Spence was preoccupied, not just with history, but its telling. When I asked him why he chose to study Chinese history, he compared the field with mushroom picking. A novice may only find one mushroom each time he goes picking, he told me, whereas an expert seems to find them under every rock. Sometimes you look among leaves, sometimes you search in the wet soil, and occasionally you look for hours without finding anything, and then suddenly come across a hollow tree filled with mushrooms just waiting to be harvested. China, as he saw it, is a land replete with drama, rich historical records, and countless stories worth telling. It was a forest filled with mushrooms — provided you knew where to look.

However, just finding mushrooms is not enough – they need to be cooked. This is the part of his work Spence found the most challenging. In our interview, he brought up what he believed to be his best piece of writing – the final paragraph of the preface to “The Death of Woman Wang”:

“My reactions to woman Wang have been ambiguous and profound. She has been to me like one of those stones that one sees shimmering though the water at low tide and picks up from the waves almost with regret, knowing that in a few moments the colors suffusing the stone will fade and disappear as the stone dries in the sun. But in this case the colors and veins did not fade; rather they grew sharper as they lay in my hand, and now and again I knew it was the stone itself that was passing on warmth to the living flesh that held it.”

“I remember I wrote that 40 years ago,” Spence recalled. “I was so happy to be able to write something like that.”

After our interview was over, I excitedly returned to my dormitory. To my shock, however, the file from the voice recorder wouldn’t play. I quickly transferred the recording to my computer, but it wouldn’t play there either. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, I immediately called Du in Beijing and asked if he had the full recording. He told me that his was so bad it was practically unusable. We were both so engrossed in listening to Spence that we completely forgot to check something so basic.

With much trepidation, I told Chin what had happened and asked if her husband would possibly agree to another interview. “I’ll call you back later,” she said, unsure what his response would be. “He’s never re-sat an interview.” Twenty minutes later, she called to say that he’d do it.

So, that night, I found myself back in Spence’s living room. He smiled and offered me a cup of tea. He was clearly tired, but after we finished, he stood up and asked his wife if she was in the mood to celebrate. “If it wasn’t for the recorder malfunctioning this morning, we wouldn’t have enough reason or be in the right mood to celebrate tonight,” he joked.

Not long after I returned to China, I was reunited with Spence and his wife. From late February until early March 2014, the couple visited the country to conduct research and meet with scholars in Beijing who had taken part in the exchange program. That fall, I found a position at Yunnan University in Southwest China and made sure to tell Chin at the first opportunity. The couple joked that now they’d have somewhere to stay when they visited the province.

Unfortunately, that trip never came to pass. Spence and Chin never made it to Yunnan: Their 2014 trip was their last to the country as a couple. When I heard the news that Spence had died, I was sad. But I also couldn’t help but think, perhaps he’ll finally get to share that drink with Sima Qian.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

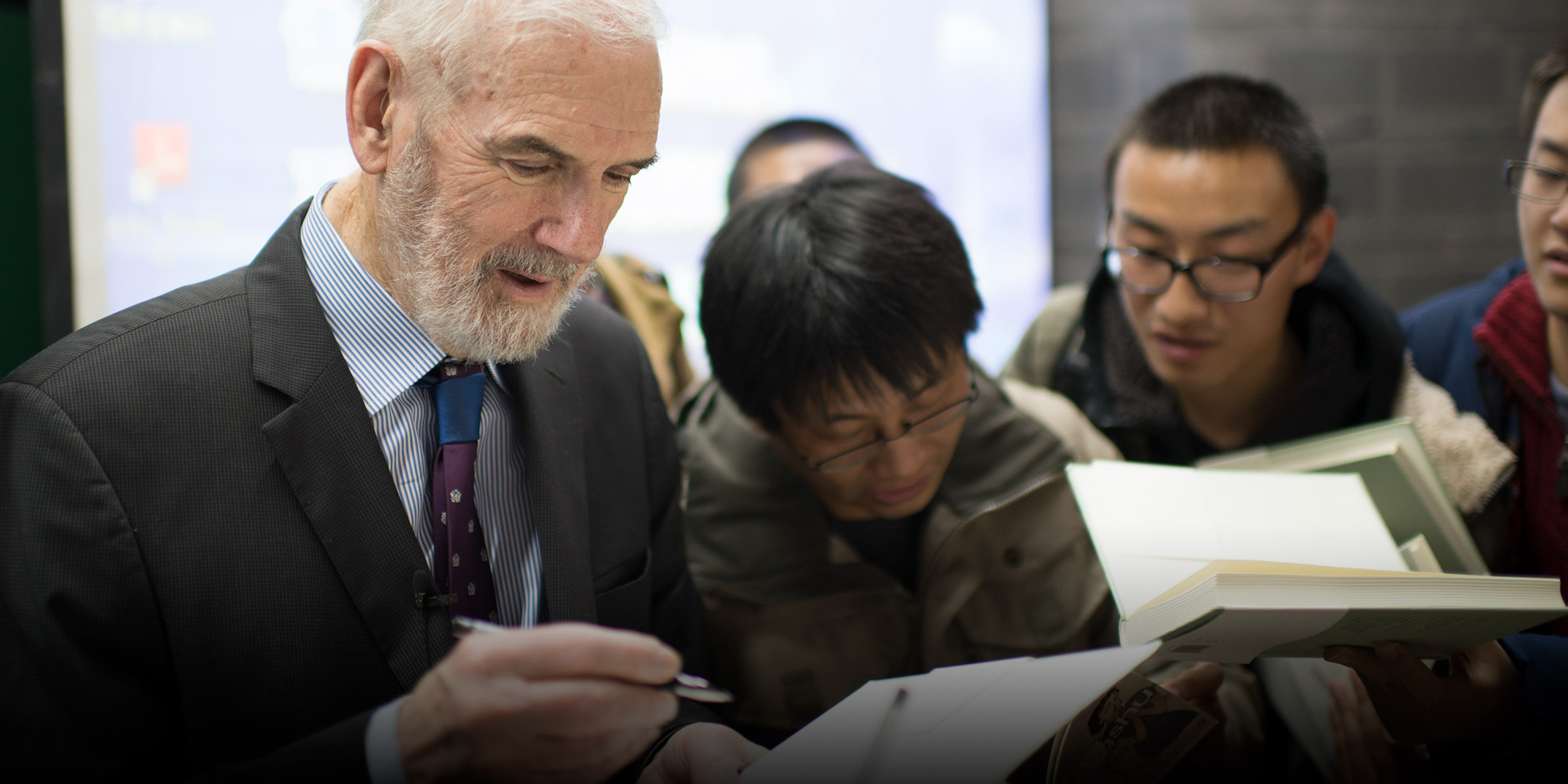

(Header image: Jonathan D. Spence signs a copy of his books after a lecture at Peking University, Beijing, Feb. 28, 2014. People Visual)