How Sixth Tone Readers Remember Beijing’s First Olympics

It wouldn’t be quite true to say that the Olympics made modern Beijing — but it wouldn’t be far wrong. Between 2001 and 2008, the capital was a flurry of development — subway lines, monuments, developments, informal dwellings for migrant workers — and a remarkable time. When we asked readers to share their memories from that time, this is what we learned.

I was a language assistant in a school in Xinjiang between 2007-08. I gave my middle school students an assignment to describe their ambitions in English. I was surprised when almost every student replied their ambition was to travel to Beijing (many for the first time ever) to volunteer for the 2008 Olympics. — Holly

China’s first Olympics were seen as a national achievement, and a unique moment of international recognition — you could compare it to the way Americans must have felt after the first moon landing.

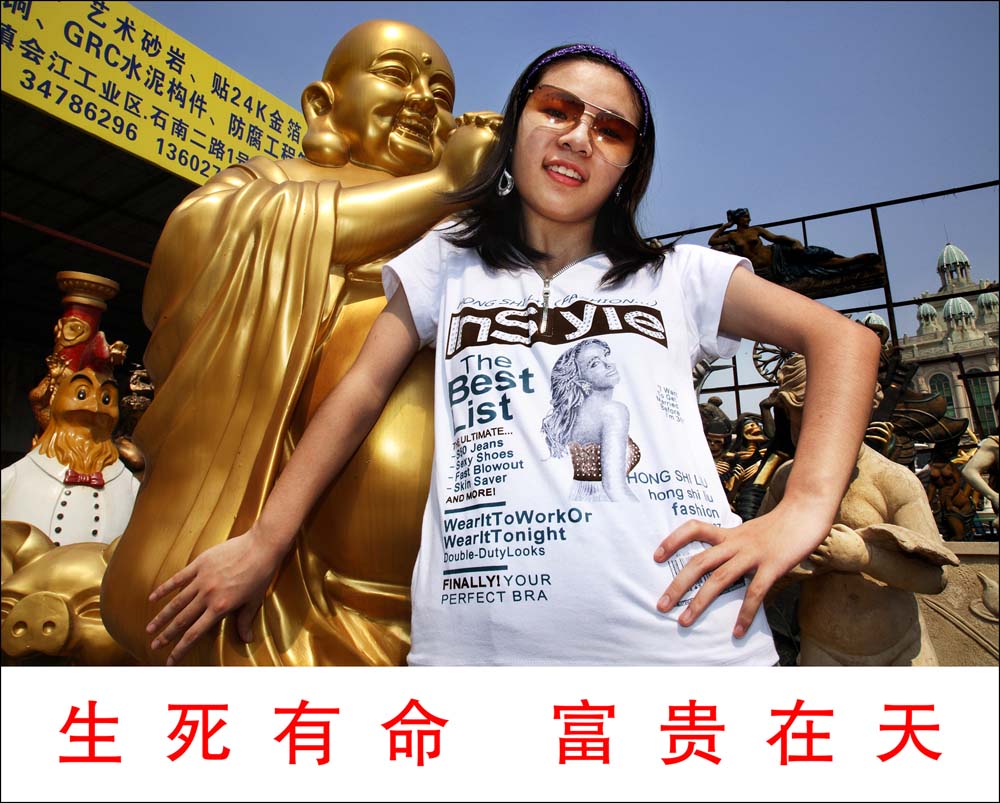

As the games approached, volunteers and tourists — domestic and international — poured into the city. Photographer Zhang Ou documented young people in the city the month before the games, pairing the images with Olympic slogans.

The photographs in this series were all taken in Beijing one month before the 2008 Olympic Games. At that time, national pride was riding high. There was a hope of this unprecedented success on the international stage. — Zhang Ou

The Olympics defined travel to the city years before they took place.

In 2007, when I was 10 years old, my teacher took us to Beijing to participate in a national concert called “Heart of the Olympics,” held on the Great Wall at Juyongguan a year before the start of the Olympic Games. I spent most of my time in Beijing rehearsing intensely the performance, so I didn't get much impression of the place. — Sumin

Ten-year-old me knew little about the 2008 Olympics until I had to visit Beijing in 2007. I vividly remember three things about the airport: a) its massive size; b) the omnipresent phrase, Beijing huanying ni, which means “Beijing welcomes you”; and c) the incandescent Olympics ads and souvenirs such as the cute mascots — the five Fuwa.

Yes, Beijing welcomed me.

“Ma Ma, I want Fuwa! I want Fuwa! I want Fuwa!” I instantaneously felt connected to the five Fuwa because of their names — Beibei, Jingjing, Huanhuan, Yingying, and Nini — because my name is Lulu.

Maybe I could be part of their squad, too, I thought. Maybe I could be a new yellow Fuwa because that was my favorite color, I imagined.

But, no. I learned the truth: that together, their names form the sentence Bei-jing huan-ying ni, "Beijing welcomes you." My name, Lulu, would never fit into this sentence.

My mom answered, “Shh, they are overpriced at the airport. We are here in Beijing already, and we will buy you some next time.”

Despite her promise, I worried. I really, really wanted the cute Fuwa. I wanted them more than I wanted to move to a foreign country. — Lulu Zhou

For many, the first impression was upheaval. It felt like half the city was a construction site, as the city sprouted three new subway lines, some half dozen ready-made landmarks from blue-chip international architects, and miles and miles of new low-rise development in the fast-growing suburbs. The scale of the construction felt cyclopean. An estimated 1 million migrant laborers were among those drawn into the capital.

Photographer Ralph Steinegger followed the construction in 2004:

I lived in Beijing in 2004 and remember the time very vividly. It was a very exciting time to be in Beijing, with the country opening up, boundless opportunities everywhere, with construction dust in my eyes, witnessing surreal street scenes and everyday clashes of the old and coming China. — Ralph Steinegger

The only thing I remember close to the 2008 Olympics were the endless rows of rose bushes that were planted in the middle of the main highways, and they all blossomed in time for the Games. Literally miles and miles of multi-colored roses. Those rose bushes are still there today and blossom each year during the Beijing summer. — Yves Ayoun

There was also a campaign for order: don’t spit, don’t cut in line, and don’t jaywalk, Beijing residents were told, lest you make us look bad in front of the foreign guests. The city installed white railings on many roads to stop jaywalking, in case the message didn’t get through.

At the time I lived off of Chengfu Road, in Wudaokou. Fellow foreigners joked it was the foreign ghetto of Beijing. In my small world, the chief attraction besides my employer was the (foreign-owned) bar D-22, located in an extremely nondescript strip of shops at the eastern end of the road. But where I lived, Chengfu Lu was a quiet crosstown road in a leafy and even bookish corner of Beijing. In the lead-up to the Olympics, that changed as the road was widened, bike and pedestrian lanes were put in, and white railings were rigorously applied along the roadsides. — Matt Turner

On Aug. 8, 2008, the Games began. The opening ceremony was viewed around the world (but none of our correspondents saw it in person).

When the Olympics took place in August 2008, I had already spent one whole year in the US, and I missed China terribly. Seeing the Olympics digitally, I wished I could be in Beijing instead. I wondered how the world would start to perceive China differently because of the Olympics? — Lulu Zhou

I watched the 2008 Olympics Opening Ceremony with my in-laws on a large-screen TV in their 22nd-floor apartment. We sat there eating watermelon slices, silent as the dancers, singers, athletes, and dignitaries danced, sang, jogged, and waved their hands from the screen. The fireworks were grand and organized, completely unlike the chaotic New Year’s fireworks people let off in hutongs and massive intersections. My brother-in-law, who worked in greenscreen technology, directly helped with some of the displays. During constant phone calls to his co-workers, he pointed out his contributions as they appeared on the screen, including the firework “footprints” that walked across central Beijing. I looked out the window towards hazy, flashing lights in the Olympic Village. Sounds of celebration broke through the traffic all the way to my in-laws’ apartment, in Wangjing…

After watching the Olympics Opening Ceremony that year, I took the elevated train home. Line 13, which I took back to Wudaokou, was standing room only even late that night. In the train car I ran into one of my students, who was returning to her dorm after volunteering all day at the Olympics. At some point, the term “Olympic generation” was seriously proposed as a name for her demographic, as though the Olympics would be her defining moment as she transitioned into independent adulthood. But “post-’90s” stuck, following an already-established tradition of “post-” ages. Naturally, the collective enthusiasm about the 2008 Olympics faded as time went on.

For her part, standing there in the train car, she seemed equal parts exhausted and satisfied. She had done her job, and the Olympics was a go. — Matt Turner

Based on a non-scientific sample, Sixth Tone concludes that the most memorable figure of the 2008 Games was “fastest man alive” Usain Bolt. Three different correspondents brought up his win, and shared photos of it.

The highlight for us: athletics competition

How fast long jumpers are, that becomes clear to us live only.

For the 100m final with Bolt we have unfortunately got super unfavorable seats. Crap!

We go to the opposite side and see if we can somehow cheat our way into a better section.

Two very dear Swiss journalists see my two kids on the corridor looking around for good places and immediately we can go to their journalists’ corner — my god such a great place to see the finish line.

And then Usain Bolt wins with a world record and we can almost smell his sweat, so close are we.

He and his golden shoes.

The stadium vibrates. — Petra Vogelsang

Some visitors describe the games as a city-wide carnival.

And there was stuff — Fuwas, ticket stubs, commemorative mugs.

Finally, it ended. The Olympics grounds were reabsorbed by the neighborhood as a vast park, and the city went back to its breakneck period of expansion.

In 2007, the streets of Beijing that I saw were teeming with joy, pride, and hope. Everyone was ecstatic for the Olympics, for the world to see them, for China to show a different side of herself to others.

In 2017 and 2018, however, the streets of Beijing I saw were full of stress, anxiety, and despair. The glamorous, rapid economic developments have deepened those socioeconomic inequities between the haves and the have-nots and between the locals and the migrants, who have left rural China in search of better lives and the “Chinese Dream.”

This population’s labor played a vital role in building the Beijing National Stadium that held the grandiose 2008 Olympics and, more generally, in building Beijing.

Indeed, the urban landscape of Beijing never stops changing. Beijing in the summer of 2018 felt different from Beijing in the fall of 2017. — Lulu Zhou

Correction: A previous version of this article mistakenly gave Matt Turner's name as Mateo Tornero.

(Header image: Courtesy of Ralph Steinegger)