China’s Top Filmmaker Is Older and — Maybe — Wiser

In early January, officials in charge of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics finally acknowledged one of the Games’ worst-kept secrets; the opening ceremony would be hosted by the biggest name in Chinese cinema: Zhang Yimou.

Zhang’s appointment surprised no one. One of the country’s premier directors and visual artists, Zhang is among just a handful of people in the world with relevant experience, having masterminded the eye-popping, extravagant opening ceremony for the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Outside China, however, the 72-year-old’s reputation has taken something of a hit in recent years. Back in 2008, Zhang was still relatively fresh from making the jump from arthouse auteur and director of critically celebrated and subversive films like “Red Sorghum” and “The Story of Qiu Ju” to a crossover commercial star in charge of mainstream martial arts epics like “Hero.” His work on the opening ceremony seemed like a chance to cement his status as one of the most important directors in the world. Instead, his ensuing films repeatedly failed to connect with global audiences — none more so than 2016’s disastrous “The Great Wall.” The film, which starred Matt Damon as a European mercenary defending China from computer-generated monsters, seemed to suggest that Zhang had lost his way.

Compounding matters, Zhang’s return to his arthouse roots after “Great Wall” never got off the ground. In February 2019, Zhang had to pull his Cultural Revolution film “One Second” from the Berlin Film Festival after failing to secure a screening permit.

At a time when Asian directors like Hirokazu Koreeda and Bong Joon-ho are taking global cinema by storm, Zhang’s star is fading. Today, many international film critics have written the once-great director’s career off for dead.

That’s a mistake. Although Zhang’s fame has dimmed internationally, within China, he has made a surprising comeback in recent years, both critically and commercially. Last December, he won his 10th Golden Rooster award — the Chinese mainland’s equivalent of the Oscars — for the spy thriller “Cliff Walkers.”

If you’re curious what Zhang might have up his sleeve for a follow-up to his swaggering effort at the 2008 Olympics, his appearance at the Golden Rooster awards ceremony might offer some clues. The Zhang who took the stage to accept the award last December bore little resemblance to the brash auteur of yesteryear. Instead, he seemed almost humble, telling his audience that, “A director is a craftsperson; we must respect the spirit of craftsmanship.”

Zhang has always been a master of his craft, but this was something different. No longer at the vanguard of film, this is how Zhang wants to be seen now: not an auteur, but something even rarer in contemporary Chinese film circles, a wily old master.

Zhang has always courted controversy. When he burst onto the scene with back-to-back Oscar nominations for Best Foreign Language Film for 1990’s “Judou” and 1991’s “Raise the Red Lantern,” international critics hailed his bold experiments in composition, color, and sound editing. However, Zhang’s portrayals of concubinage, domestic quarrels, and lust distorted by social convention unsettled audiences in China. Some domestic filmgoers accused the director of being in love with the ugly side of traditional Chinese culture and “too welcoming” of Western aesthetics.

The release of “Hero” in 2002 marked a dividing line in Zhang’s career, both artistically and professionally. While previous films like 1988’s “Red Sorghum,” 1992’s “The Story of Qiu Ju,” and 1999’s “Not One Less” were all heavily colored by Zhang’s personal style, they also benefitted from their basis in strong source material. As they were adaptations, the original texts came laden with their own powerful imagery and could exist independently of their cinematic counterparts. Starting with “Hero,” however, Zhang’s hidden ambition came to light: he seemed to want to transcend text and traditional theatrical constructions altogether, thereby freeing himself to experiment with purely audiovisual storytelling.

Today, China is home to the biggest box office in the world, but in the early 2000s, things were different. If Zhang wanted to take cinema to the next level, first he needed to put it on solid ground. So he exercised restraint, at least by his standards, after the success of “Hero.” After that movie’s premiere, he told interviewers that, if China wanted to nurture a true film industry, someone would have to take the lead. His output over the ensuing decade, from martial arts blockbusters like 2004’s “The House of Flying Daggers” and 2006’s “Curse of the Golden Flower” to the Christian Bale-starring Nanjing Massacre film “The Flowers of War” in 2011, all played it safe, as Zhang sought to put the Chinese film industry on more level financial and artistic ground.

After enduring years of solid, if unspectacular commercial filmmaking, “The Great Wall” was, in a sense, the fulfillment of a longtime wish: Zhang entered the Hollywood production ecosystem and masterminded a truly A-list production within a well-established film industry space.

Zhang had long sought to use new technologies to impose his grandiose vision on the wuxia sword-and-steel martial arts genre. In “The Great Wall,” with its scenes of female soldiers bungee jumping into battle against Chinese mythological beasts, he finally got his way.

The end result landed with a thud. The collaborative process frustrated everyone, including the always headstrong Zhang, who found the job suffocating and restrictive. The joint Chinese-American production was a debacle, turning Zhang into an international punchline. (Though in a cruel twist, “The Great Wall” actually became the highest grossing of all the director’s films.)

Despite taking a critical drubbing, Zhang has spent the years since 2016 doggedly making movies and refusing to patch up plot holes. But something did change. Between “Hero” and “Great Wall,” Zhang seemed obsessed with his own personal vision of cold steel and martial arts in feudal China, in part because these were commercially reliable subjects at a time when many Chinese production studios needed guaranteed returns.

Increasingly, that’s no longer the case, and in the five movies Zhang has completed since 2014 — the alt-history film “Shadow,” the highly political “One Second,” the thriller “Cliff Walkers,” and this year’s “Under the Light” and “Sharpshooter” — he has demonstrated an ability to fluidly adapt himself and his once overpowering style to a wide variety of genres. Freed by “The Great Wall” of some of his grander ambitions, Zhang is once again exactly what China’s film industry needs: a professional, sophisticated craftsman with the skills to make almost anything watchable.

That’s not to say Zhang’s exacting, uncompromising personality isn’t still shaping his work. At the core of almost all his films, new and old, is something cold, inflexible, and consistent: a lack of belief in love or in people. Unsettling to others as that may be, Zhang thrives in harshness. “One Second,” which revolves around a film projectionist during the Cultural Revolution, has been misinterpreted as a love letter to old films, but concealed deep in his work are bitter accusations, not happy reconciliations. In a world that is both materially and spiritually barren, Zhang argues that art cannot turn beastly people into kind souls. He is a hardened skeptic of human nature who disavows redemption.

Ahead of the 2008 Summer Olympics, when Zhang was hired to craft a paean to the same culture he’d long been accused of demeaning, fans mockingly started referring to him as China’s “national master.” They joked that he’d sold out his creative instincts to serve the state.

More than a decade later, that title has been dusted off again, but not as an insult. After the pandemic forced Japan to resort to a stripped-down opening ceremony for the Summer Olympics in Tokyo last year, Chinese social media users began clamoring for a “revival” of the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony. Younger Chinese, many of them unfamiliar with or uninterested in Zhang’s more challenging early work, remember him primarily as the architect of one of China’s shining moments on the international stage. Indeed, the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony is viewed in China as Zhang’s masterpiece, and it remains his highest-scoring work on Chinese rating sites like Douban.

Yet, running back Zhang’s greatest hit also highlights a tragedy of the Chinese film industry’s commercial success: Zhang helped lay the foundations of modern Chinese cinema, but his uncompromising values have never been fully accepted; he is appreciated for his skills rather than his vision. And in the meantime, no one has stepped up to claim the banner for the next generation. As a result, Zhang’s professional and technical qualities remain a rarity, uncommon enough that the wily old master is still China’s best bet for putting on a big show.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

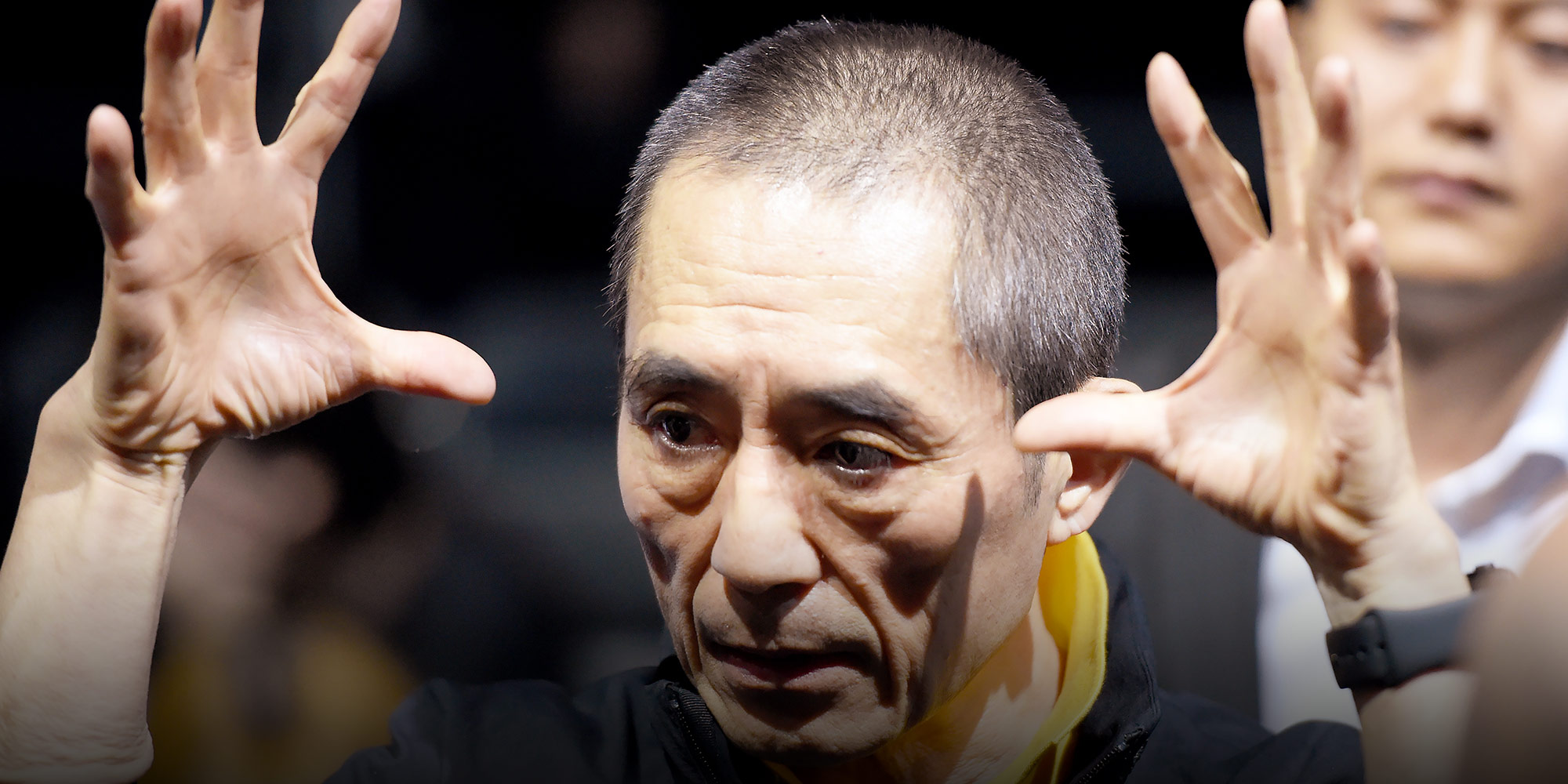

(Header image: Zhang Yimou directs performers during a rehearsal in Beijing, 2018. Hou Yu/CNS/People Visual)