Skating Toward a Revolution

By the 1920s, ice skating had taken North China by storm. A trendy new form of exercise associated with Western values and lifestyles, it was well-suited to the region’s long, cold winters. Although nationalist proponents of skating called on men to take to the ice and battle Western colonizers, skating arguably had the greatest impact on women, as ice-rinks became a stage for China’s emerging “new woman” to demonstrate her modernity.

The concept of the “new woman” was born out of the clashes between Chinese and Western cultures during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). It was, in essence, a canvas onto which reformers — most of them men — could project their imaginations of China’s future.

Progressives of the time advocated for Chinese women to model themselves after their Western counterparts, from the French revolutionary Jean-Marie Roland de La Platière to Alexandre Dumas’ fictional La Dame aux Camélias. These women, fictional and otherwise, were held up as symbols of modern civilization, and Chinese women were divided into two categories according to how well they performed idealized Western femininity. Of the two categories, traditional women — i.e., those that upheld traditional Chinese values — were dismissed as being at odds with the values of modern society. Society’s “new women,” on the other hand, were championed as icons of female emancipation who would help bring China out of the feudal era and set it on course to become a modern nation.

For women, modernity was less of a choice than an obligation. In the late Qing and early Republican eras, Chinese women were saddled with heavy responsibilities. To be deemed fit as “mothers of the Republic,” they had to both convey a positive image of China to the international community and nurture a new generation of strong, modern men and women capable of revitalizing China’s national bloodlines.

Urban women of the time largely accepted the responsibilities that came with the “new woman” label. They rejected traditional practices such as foot-binding and enrolled in the nation’s new schools, where they took part in sports, another new concept closely tied in reformers’ minds to “strengthening the nation and preserving its people.” Delicacy fell out of style in favor of “healthy beauty,” while sexual equality and free love were discussed and even pursued.

It was precisely in this context that the rising trend of ice skating found favor with “modern women” as a healthy, “Western”-approved sport in which both sexes could take part on an equal basis.

For Chinese women of the 1920s, the feeling of gliding on the ice must have resembled the feeling of heading full speed toward a revolution. In a sense, their experiences weren’t all that different from those of the “new men” of the time: Both sexes perceived a widening chasm between China’s old and new societies, between China and the world, between “weak” and “strong.”

To some, skating was truly liberatory. Xiao Shufang, the niece of famous musician Xiao Youmei, would later become better known as a painter, but throughout the 1920s and ’30s she was a famous ice-skater at rinks across Beiping, as Beijing was then known. Forty years later, recalling her memories of skating on the city’s North Sea, Xiao linked this joyful experience with the tide of social change brought about by the Xinhai Revolution that finally toppled the Qing. In her paintings of ice skating scenes, Xiao evoked the atmosphere of excitement and new possibilities that came with being young at this crucial juncture in China’s history.

However, more often than not, China’s “new women” found themselves unable to completely cast off the shackles of traditional femininity. In particular, one of the most pressing dilemmas facing women who wanted to leave the home and take on more public roles in society was how to redefine their interactions with the opposite sex. And ice skating rinks provided them with an important venue in which they could seek and test out potential solutions to this dilemma.

At skating masquerades — briefly in vogue during the Republican period that followed the Qing — it was extremely common for female performers to dress as men, and vice versa. What’s interesting is that the male characters portrayed by women typically included high-ranking figures such as nobles and judges, while the female characters portrayed by men were usually elderly aunties and matchmakers from the countryside. Female skaters’ choice to dress as men recalls one of China’s most well-known revolutionaries, Qiu Jin, who also frequently dressed in men’s clothes. “I want to first dress up as a man until my spirit, too, is male,” Qiu once said.

On one level, this reversal of gender roles reflected the ongoing destabilization of patriarchal values and helped validate the “new woman.” On another, it suggests that, although women’s status was on the rise, their self-affirmation nonetheless still depended on the appropriation of male symbols.

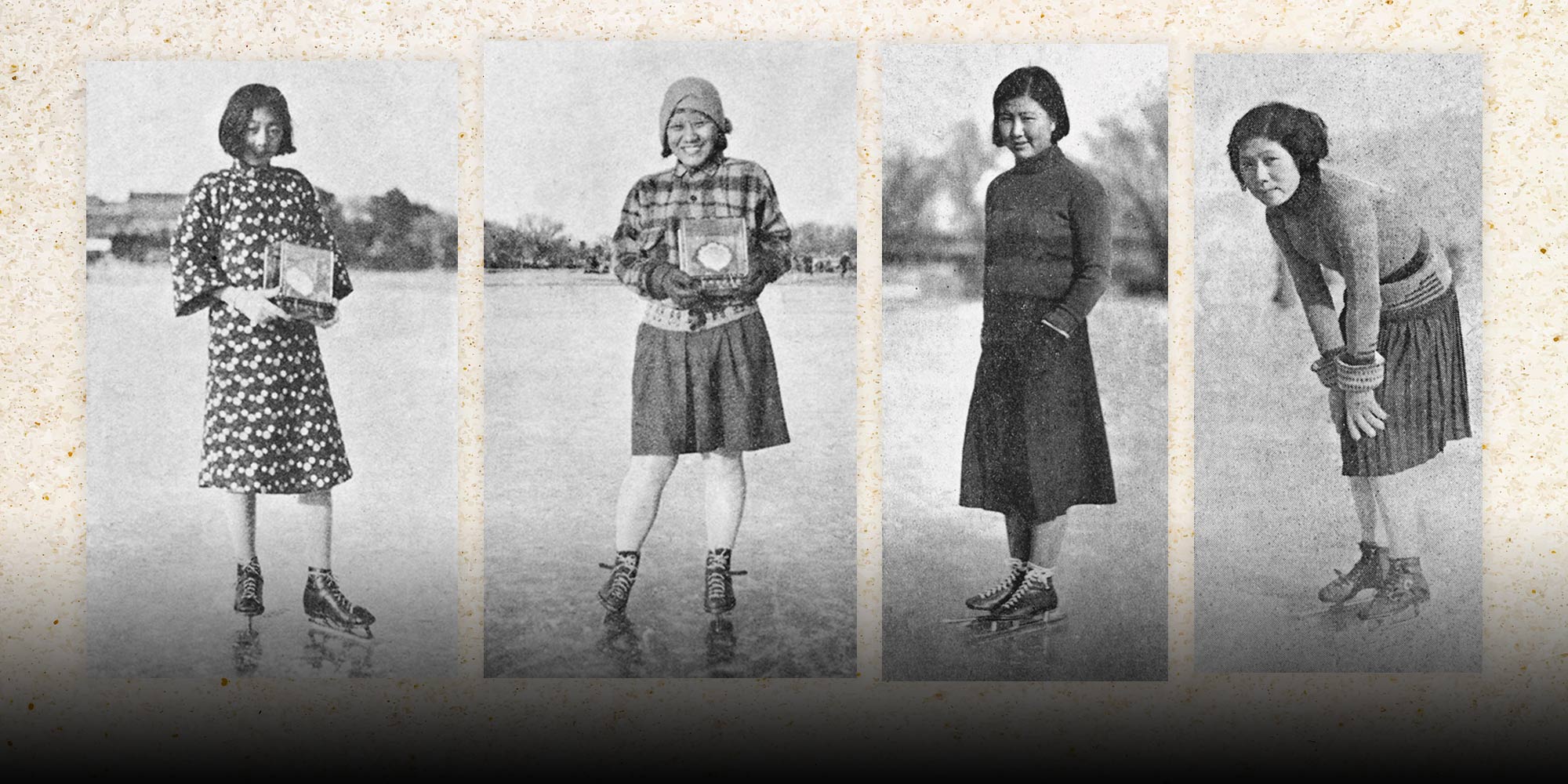

Other skaters, both at masquerade events and in their everyday lives, looked not to men, but to Western women as models for liberation. Young students in particular were a highly noticeable presence on ice rinks — with their short hair, high-collared sweaters, knee-length skirts, and meticulously practiced Western figure-skating techniques. Their graceful execution of popular moves like waltzes inspired many women to follow in their footsteps.

In their interactions at ice rinks, young men and women often consciously played the part of Western gentlemen and ladies, demonstrating their reverence for Western social etiquette. By collaborating and performing together, men and women produced new scenes of modernity and gender relations.

Though ice skating seemed to represent a plausible route to emancipation and equality, many female skaters nonetheless continued to view themselves through their male partners’ eyes, rather than see themselves as truly independent. Under the appearance of gender equality lurked the specter of misogyny.

In articles and literature about skating from the 1920s and 1930s, there is no lack of anecdotes denigrating women for their participation in on-ice performances. For example, the 1930 novella “To Moscow” by Hu Yepin highlights the ways in which both men and women were seen as using skating masquerades to advance their personal aims. In Hu’s story, Xu Daqi is an “eloquent politician” who realizes that skating masquerades are an infinitely more effective means of attracting the attention of reporters and the public than dispatches from government conferences and tries to convince his partner, Su Chang, to take part in one of these events with him. But Su rejects the idea due to her perception that female skaters were merely “making bizarre poses for the pleasure of men.” In Su’s view, skaters were simply molding themselves according to the tastes and demands of men as a means of gaining social capital.

All this is to say that, at least in their interactions with men, “new women” faced many of the same barriers as their traditional counterparts. They had gained the semblance of equality through Westernized forms of empowerment, but not the substance.

As with so many of the modern activities Chinese women participated in during the early post-imperial era, skating was a kind of controlled experiment — part of the Chinese nation’s urgent pursuit of Western-style modernity rather than a genuinely free form of expression. Women who were involved in winter sports still behaved according to their own cultural schema and constantly faced conflicts — with men, with tradition, and with their own internal values — as they struggled to redefine their identities on the ice.

China’s women have come a long way since the 1920s. Gu Ailing, an 18-year-old woman of Chinese and American descent and one of the best skiers in the world, is probably the biggest star representing China at this year’s Winter Olympics, though she is far from the only one. As we marvel at Gu’s athleticism, let’s not forget the Chinese women who braved the snow and ice before her. No revolution can be perfect, and true emancipation cannot be achieved overnight. But their courage, their contradictions, and their quiet revolutions helped lay the groundwork for everything that has come since.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; visuals: Ding Yining.

(Header image: From left to right, skaters Gao Shuzhen, Xiong Minzhen, and Lin Xiulian in the 1930s. Photos taken by Li Yaosheng, Song Xindeng, and An Guolin, respectively. Courtesy of Yang Yufei)