The Silk Road Traders Who Traveled From Kathmandu to Lhasa

The following is an excerpt from Nepali author and journalist Amish Raj Mulmi’s new book “All Roads Lead North: China, Nepal and the Contest for the Himalayas,” published by Hurst in December 2021. It has been edited for length and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

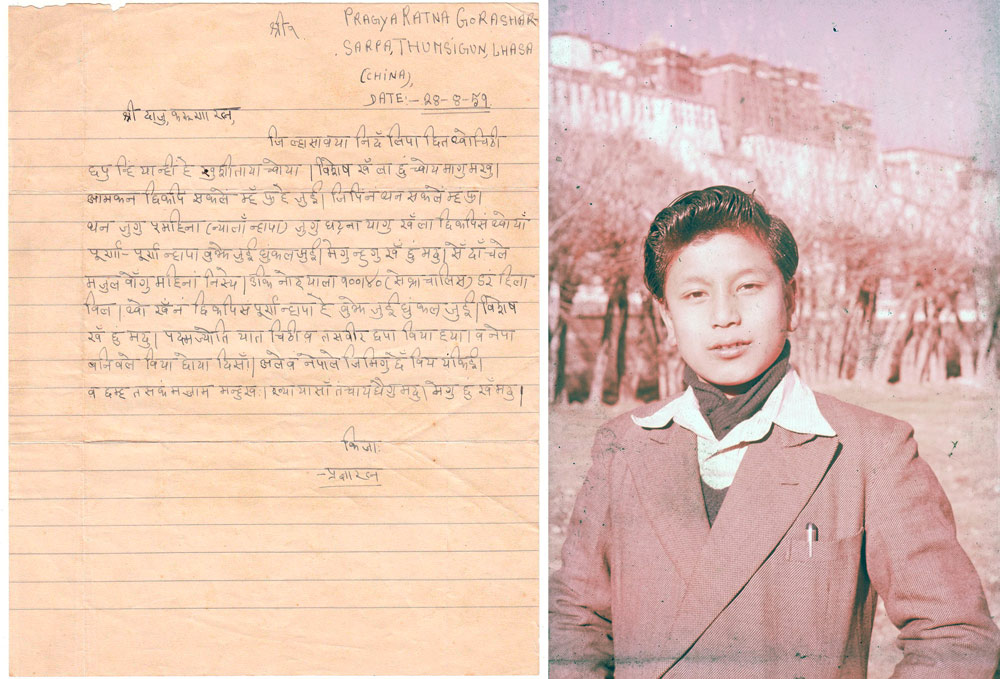

Pragya Ratna had grown up around brothers, cousins and relatives who had all been to Lhasa to trade. His cousins ran the Ghorasyar trading house from the corner of a Barkhor street square in Lhasa, dealing in everything from textiles to watches and Parker pens. Eventually, in 1956, he too went to Lhasa with a cousin. “I was told going to Lhasa was one big adventure, and you didn’t know whether you’d return or not,” he tells me.

The Newars of Kathmandu (Newar is an anglicized spelling for the Newa people) have long practiced a uniquely syncretic culture that merges aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, Vajrayana, with Brahminical Hinduism. Nepal valley — as the valley encompassing the three city-states of Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, and Patan was known even as late as the middle of the twentieth century — was a complex society where Brahminical Hinduism, which had royal patronage, existed alongside Tibetan Buddhism, which gathered momentum as interactions with the Tibetan plateau continued to grow through trade, particularly by those who belonged to the Newar Buddhist merchant caste of Urays.

Within the high-caste Uray group, multiple sub-castes find their origins in craftsmanship and commerce. Hence the etymology of surnames such as Tamrakar (“one who works with copper”), Kansakar (“one who works with metal”), and Tuladhars (“one who works with scales”), this last being the most dominant sub-caste in trans-Himalayan trade. It was primarily a family-based practice, with extended family members, cousins and relatives all incorporated under a single kothi (editor’s note: a kind of merchant establishment), which is how Pragya Ratna ended up joining a relative’s establishment.

While religion may have formed the crux of the socio-political relationship between Tibet and Nepal, trade was the backbone for cultural exchanges. With Hinduism’s caste restrictions, which forbid social exchanges with outsiders, it is no surprise that the most enterprising trans-Himalayan traders were inevitably Buddhists. Further, trans-Himalayan trade was conducted at almost every possible geographical point along the Nepal-Tibet border.

Although Newar traders conducted business in Tibet, donned Tibetan clothes, spoke the language, worshipped at the same temples and celebrated the same festivals as the locals, and even entered into relationships with Tibetan women, they rarely assimilated into Tibetan society. The traders had organized themselves into seven different guthis, an informal social order; “the Newars liked to remain within their little circles,” a biography acknowledges. Newar men lived in Tibet for years at a stretch; “I knew some of the men who had stayed for eight–nine years,” Pragya Ratna said. Most stayed at least three years.

Having left their wives behind in Kathmandu, traders would often enter into relationships with Tibetan women. The Newar women had little choice; a woman married to a trader recounts a song commonly told to children at the time: “The coral from Lhasa / brings a quarrel back home / ignoring the fights / the man hugs his second wife.” Daughters from such relationships were considered to be Tibetan citizens, whereas the sons were considered Nepali citizens, with the same extraterritorial rights accorded to them as their fathers.

The sons often acted as local representatives in their father’s trade. “Nepalese traders relied on their half-Tibetan offspring to help them maintain a commercial presence in Tibet during their extended absences. While the Nepalese may have held children of these mixed marriages in contempt, they relied enough on the Khatsaras’ [khacharas’] role as guardians of lucrative Nepalese business interests to jealously guard their legal status within Tibet.” They also emerged as one of the most dominant foreign presences in Lhasa, a city teeming with traders from as far as Kashmir and Central Asia.

The ambiguous status of the half-Tibetan, half-Newar sons was one of the key points of tension between Nepali and Tibetan authorities. Tibetan authorities regularly accused them of “unfair business practices and the perception they were hiding behind their Nepalese foreign parentage.” Further, the social exclusion and tenuous legal position they held in Nepal did not make it easy for the Tibetan-Nepalis. Although the sons were granted the same privileges as Nepali citizens, and were occasionally used by the Nepal government as spies, such as during the Younghusband expedition, “the striking feature” of the government policy towards them was one of exploitation and lack of concern. They were “politically ignored, economically exploited and socially discarded by both Nepal and Tibet,” with the Nepal government acknowledging them as citizens only “to exact tax and free labor.” Further, they were also not welcome in Kathmandu, where they could, under customary Nepalese law, claim a share equal to that of the “pure” Newar sons from their father’s estate.

Existing accounts on “Lhasa Newars,” as such traders are colloquially called, tend to gloss over the relationships between Newar men and Tibetan women. The reasons for why Newar women did not accompany their men tend to focus on the hardships of the journey, of how they were not up to it and the social taboos around women travelling. Folk literature also highlights the viraha, or pain of separation, between the Newar wife and husband. One of Nepali literature’s epic poems, Muna Madan, tells the story of a newly married couple in which the husband has to leave for Lhasa to make money. The poem is based on a Newar folk song titled Ji Waya La Lachi Maduni (“It’s Not Even Been a Month Since I Came”) that begins with a newly-wed woman telling her mother-in-law, “Not even a month has passed since I came to this house, and your son is already saying he will go to Tibet. Stop him just this once!” But Tibet is where fortunes are made, and the son replies, “Oh wife, I shall not stay long in Tibet. I shall return after staying only one or two years.”

But the rigid caste rules of Newar society, and the claim the male offspring could make on the wealth of their fathers, often made them outcastes in Kathmandu society, despite polygamy being legal and acceptable at the time. “[The sons] were of course not welcome in their father’s Kathmandu homes or in the valley … They were not of acceptable status for marriage to proper Uray girls either.” Tamla Ukyab, a former Nepali bureaucrat who was consul general in Lhasa in the 1980s, told me there were several legal disputes in Kathmandu after 1959, when the Newars’ Tibetan families moved to Kathmandu.

That said, having a second Tibetan wife was not really considered a scandalous affair back in the day. “It was common,” Pragya Ratna said. “People didn’t really care about it. The Tibetan wives were usually bought another apartment. The two families didn’t live together. The husband paid the second wife’s expenses. There weren’t any issues in society, at least as far as I know.”

Most writing on the Lhasa Newars tends to focus on the romanticism of the trade: the long caravans, the difficult terrain, surviving bandits, cold winds and extreme temperatures; the imagery of the Silk Road, with merchants selling their wares from across the world in alien lands; the land itself a harsh mistress. Rarely is there an admission of the personal space; rarer still is the presence of women — either the wives the men left behind in Kathmandu, or the women they married in Tibet. The children are absent altogether. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is the ruling Shah-Rana emphasis on Hindu purity.

But these are all ex-post-facto explanations that do little to justify the uncomfortable histories of the Tibetan wives and their offspring. Further, there has been little acknowledgement that Tibetans had a role to play in the success of Newar traders in Lhasa — a prosperity that endured, as can be seen in the many businesses the descendants of Lhasa Newars have founded in Nepal.

Amish Raj Mulmi is a journalist and writer from Pokhara in Nepal.

Editor: Bibek Bhandari.

(Header image: An archive photo showing members of Nepal’s Chamber of Commerce in Lhasa, 1950s. From Internet Archive)