Can-Do: How China’s Canning Industry Preserved Local Tastes

You’ve probably heard of Cup Noodles, but what about canned kung pao chicken? To appeal to the country’s overworked, underfed young consumers, Chinese canned food brands have started marketing “meals for one,” a sort of TV dinner for the mandatory overtime era. Inside each can, you’ll find entire dishes, from kung pao chicken to fish-flavored pork.

The “meal for one” format may be new, but it’s just the latest in a long line of attempts to convince Chinese of the merits of eating out of a can. Interestingly, the most successful of these products haven’t been basics like tuna or fruit, but full-fledged regional delicacies: chicken stew from Shandong, ham from Yunnan, spicy yellow croaker from Liaoning, and black bean and dace fish from Guangdong. There are even desserts in a can, like peanut soup from Fujian and canned sweet coconut soup from the tropical island province of Hainan.

The dominance of local producers and products in China’s canned goods market is linked to how the country first came to accept canned goods — imported products initially viewed with deep skepticism. The first canned goods were imported into China by foreign merchants in the 1870s and 1880s, with local consumers treating them as curiosities rather than staples. By the early 20th century, only a few canned items — milk, coffee, and lobster, somewhat — had developed a market among a small subset of wealthy Chinese shoppers, most of who had ties to the West.

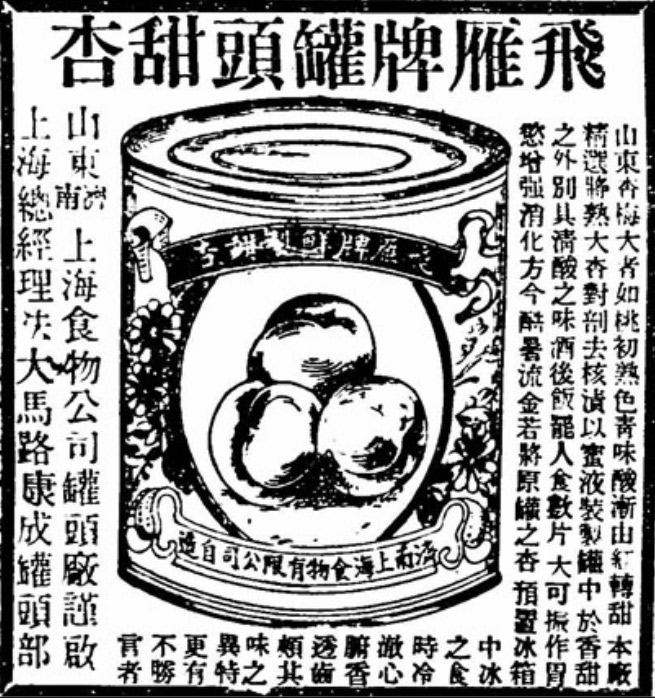

It wouldn’t be long, however, before a group of local Chinese canneries began to wonder if the problem wasn’t the cans, but their contents. Enterprising local business owners began to research and develop canned regional specialties, and by 1915, merchants from Yancheng in the eastern province of Jiangsu were selling canned Shanghai-style drunken fish and crab, produced by local companies to meet local tastes. Soon, popular family dishes like winter mushroom chicken were being canned and sold by Chinese companies, and over the course of the 1920s and 1930s, well-known brands like Shanghai’s Guan Sheng Yuan rolled out new canned vegetarian dishes, including the stir-fried favorite “Buddha’s Delight.”

Ads for canned goods during this period often emphasized their freshness and supposed hygienic qualities. The main form of food preservation for Chinese at that time was pickling, in which large amounts of salt were used to preserve meat or vegetables. Because canned food was fresher than pickled food, and because it did not sap the fresh flavor of the ingredients the way pickling did, cans soon caught on, at least where they were widely available. And because cans were also easier to transport, especially before the advent of cold chain logistics, their rise allowed dishes popular in one region to travel far more freely and widely than ever before.

Take Ningbo bamboo shoots, for example. A Ningbo specialty, once canned, the dish spread from this Yangtze River Delta port city through the rest of the region, before eventually hitting Shanghai. In the process, the cuisine of the entire Delta region was altered. After consumers and businesses in the increasingly international metropolis of Shanghai embraced the dish, it spread even further: Ahead of the 14th Summer Olympic Games in 1948, Shanghai-made canned bamboo shoots were issued as rations for the Chinese delegation sailing to London.

Between 1950 and 1953, China’s participation in the Korean war resulted in a boom in demand for canned goods. A number of canneries sprang up to supply the country’s volunteer armies on the peninsula, and the canning industry expanded rapidly. After the war ended, however, those manufacturers faced a problem: with domestic demand for canned goods still quite low, who would buy their excess stock? The answer came in the form of exports, as high-quality domestic canned goods from China were sold on international markets. From the late 1950s to the mid-1980s, Chinese-made canned goods became one of the country’s key export industries, reaching dinner tables in the Soviet Union, Western Europe, and Japan.

At home, however, the high cost of metal in pre-reform China, to say nothing of the fruit or meat inside, turned canned goods into a luxury item, one generally reserved for pregnant women, the sick, and others in need of concentrated boosts of nutrition. Although not necessarily popular, they were rare and costly enough that gifting canned foods during major holidays like the Lunar New Year or Mid-Autumn Festival became a way to give “face” to respected relatives or peers.

That changed after China’s economy took off in the 1980s. After successive waves of marketization, consumers began viewing the largely unregulated food industry with suspicion, and increasingly cheap canned foods, somewhat unfairly, became associated with the use of dangerous additives.

The industry still hasn’t recovered, though not from lack of trying. Recently, Chinese canned goods companies have embraced the trend toward “national chic,” attempting to woo consumers by increasing their offerings and playing up Chinese cultural elements in their packaging. Other firms have emphasized the convenience of canned goods, positioning their products as “healthy” alternatives to oily, salty takeout dishes.

Through it all, the industry has remained a patchwork of local companies and delicacies. Chinese consumers never quite embraced this revolution on the same scale as their counterparts in the United States or Europe, but there’s no denying that canned goods reshaped tastes and brought together once disparate local cuisines. That’s worth celebrating, even if you’re not yet ready to make a meal out of canned fish-flavored pork.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

(Header image: A collage shows ads for canned kung pao chicken, beef, and meatballs. Visual elements from JD.com and People Visual, reedited by Sixth Tone)