How Shanghai’s Coffee Culture Brewed Up a Revolution

In the 2021 film “B for Busy” — one of last year’s sleeper hits — the characters are anything but overworked. Members of Shanghai’s idle rentier class, they spend their days flirting, taking art lessons, and drinking coffee. In this fantasy version of Shanghai, even street cobblers treat their coffee breaks as sacred, grinding their own beans and telling off the protagonist in Shanghai-accented English for interrupting “coffee time.”

Shanghai’s infatuation with coffee has become shorthand for what makes the city different from the rest of the country: Coffee is seen as a symbol that either denotes its tolerant, Westernized culture — or its petit bourgeois affectations, depending on your point of view.

As the louche lifestyles of the “B for Busy” set suggest, it’s a stereotype Shanghainese themselves embrace. Although there is some truth to the idea that coffee represents the epitome of the bourgeois Shanghai lifestyle, the early history of the city’s coffee culture is surprisingly complex. During the colonial period, coffee houses weren’t just icons of modern, Westernized lifestyles and aspirational middle-class living; they were also clandestine meeting grounds where proletarian figures brewed up revolutionary ideas.

The history of coffee in Shanghai can be traced back to the city’s opening to foreign trade in 1843. But it wasn’t until the Republican period (1912-1949) that the drink became a part of everyday life for most residents. In the 1930s, the ruling Nationalist party began promoting what it called the “New Life Movement,” which sought to teach Chinese more modern, healthier ways of living. Although the New Life Movement’s impact varied by region, it helped convince many middle-class Chinese families to adopt coffee as the last course of a formal, filling Western meal.

Coffee culture’s rise changed more than consumption patterns. The practice of drinking coffee after a meal became part of China’s “new family lifestyle” ideal. According to traditional Chinese custom, women were not allowed to eat at the same table with men. But during the coffee course, they were invited to join the table and chat with their male counterparts. This, in turn, encouraged the formation of a new archetype of womanhood, as women were expected not just to brew coffee for their guests, but also to entertain them with witty and intelligent conversation.

But it was through the city’s numerous cafés and coffee shops that the beverage had its most lasting impact on Chinese society. In the 1920s and 1930s, a wave of international immigration led to a boom in cafés citywide. At first, Russian emigres fleeing the October Revolution clustered along the then-Avenue Joffre in newly opened cafés, including the famous Tkachenko Bros., DD’s, Renaissance Café, Constantine, and The Balkan. Then, beginning in the 1930s, Shanghai received tens of thousands of Jewish refugees from Germany and German-occupied areas of Europe. They built their own temples, schools, and stores — and opened numerous cafés in the Hongkou area, including the Delikat Café, Europe Café, Bataan Café, and Weiner Café.

These cafés were not only places where homesick foreigners could go for a taste of the old country, but also gathering places for local intellectuals, members of the middle class, and the occasional proletarian revolutionary. For example, the Coffee Café, also known as the Gongfei Coffee Hall, which opened in October 1929, was the earliest bookstore in Shanghai with a café and quickly became a popular hangout for left-wing writers. In his memoir, the playwright Xia Yan recalls meetings held by the League of Left-Wing Writers at the Gongfei: “Meetings were generally held once a week, sometimes every two or three days, in a small room on the second floor of the Gongfei Coffee Hall that could accommodate twelve or thirteen people.” Many playwrights set their plays in cafés, such as Tian Han’s one-act play “A Night in a Café” and Xu Jie’s “Temptation of a Gypsy.”

The tension between the middle-class trappings of these cafés and the proletarian aspirations of the writers who gathered within their walls did not go unnoticed. In 1928, the novelist Lu Xun published an essay entitled “Revolutionary Café,” which satirized another left-wing coterie: the Creation Society. The Creation Society consisted of a group of Chinese literati who, like Lu Xun, had studied in Japan, including Guo Moruo, Yu Dafu, and Tian Han. In the essay, its members sit in a beautiful café, talking and sipping “proletarian coffee” — their lives far removed from the struggles of the country’s peasants and workers. At the end of the essay, Lu Xun suggests that guns may be more useful than pens during revolution and calls for practical contact with the masses.

Lu Xun eventually made peace with the members of the Creation Society, and later even joined forces with them to form the League of Left-Wing Writers at the Gongfei Coffee Hall. But he never quite warmed to their coffee habit. Despite frequenting cafés to write and attend meetings, his contemporaries wrote that he rarely drank coffee, opting instead to brew his own green tea.

Not all revolutionaries who gathered in Shanghai’s cafés were merely playacting. Over the course of the 1930s, underground agents of the Communist Party of China (CPC) often used cafés as meeting places. The early CPC leader Chen Yun, for example, was among those who frequented the Gongfei Coffee Hall, and Lu Xun himself helped the CPC pass notes between members at clandestine meetups in the café.

Of course, the choice of venue had less to do with their desire to drink “proletarian coffee” than the environment of the typical Shanghai café. Coffee houses were crowded and noisy, but still relatively private, making them well-suited for clandestine work away from prying eyes and ears. This penchant for plotting in cafés also shows up in the Eileen Chang novella “Lust, Caution,” in which the heroine initiates an assassination attempt against a Japanese collaborator by placing a discreet phone call from a coffee shop.

Despite the revolutionary pedigree of Shanghai’s coffee scene, it wasn’t until after the end of the Second World War that the drink went from being the preserve of foreigners, the upper-middle class, and members of the literati to something the working classes could enjoy. In 1946, China’s Nationalist government and the United States signed “The Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation,” which allowed American goods to flow freely into the Chinese market at a low price. Soon, foreign-made products squeezed out their Chinese competition. According to contemporary records, in the late 1940s, 50 grams of Longjing tea cost 5,000 yuan — more than 10 times the price for an equivalent amount of S&W coffee imported from the U.S.

Soon, open-air coffee stalls began to appear in large numbers on Shanghai’s streets. These stalls were often little more than roadside counters with cloth tarps overhead. Most of the consumers who patronized the stalls came from the city’s middle and lower classes, attracted by the promise of a cheap boost of caffeine.

By the end of the decade, the floor would fall out from under the Chinese economy, in part thanks to one-sided deals like the above-mentioned Sino-American treaty. But for a brief period, coffee was the social glue that held Shanghai society together. Men and women, civil servants, and rickshaw pullers sat together, drank together, and forged the basis of a coffee culture that persists to this day.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

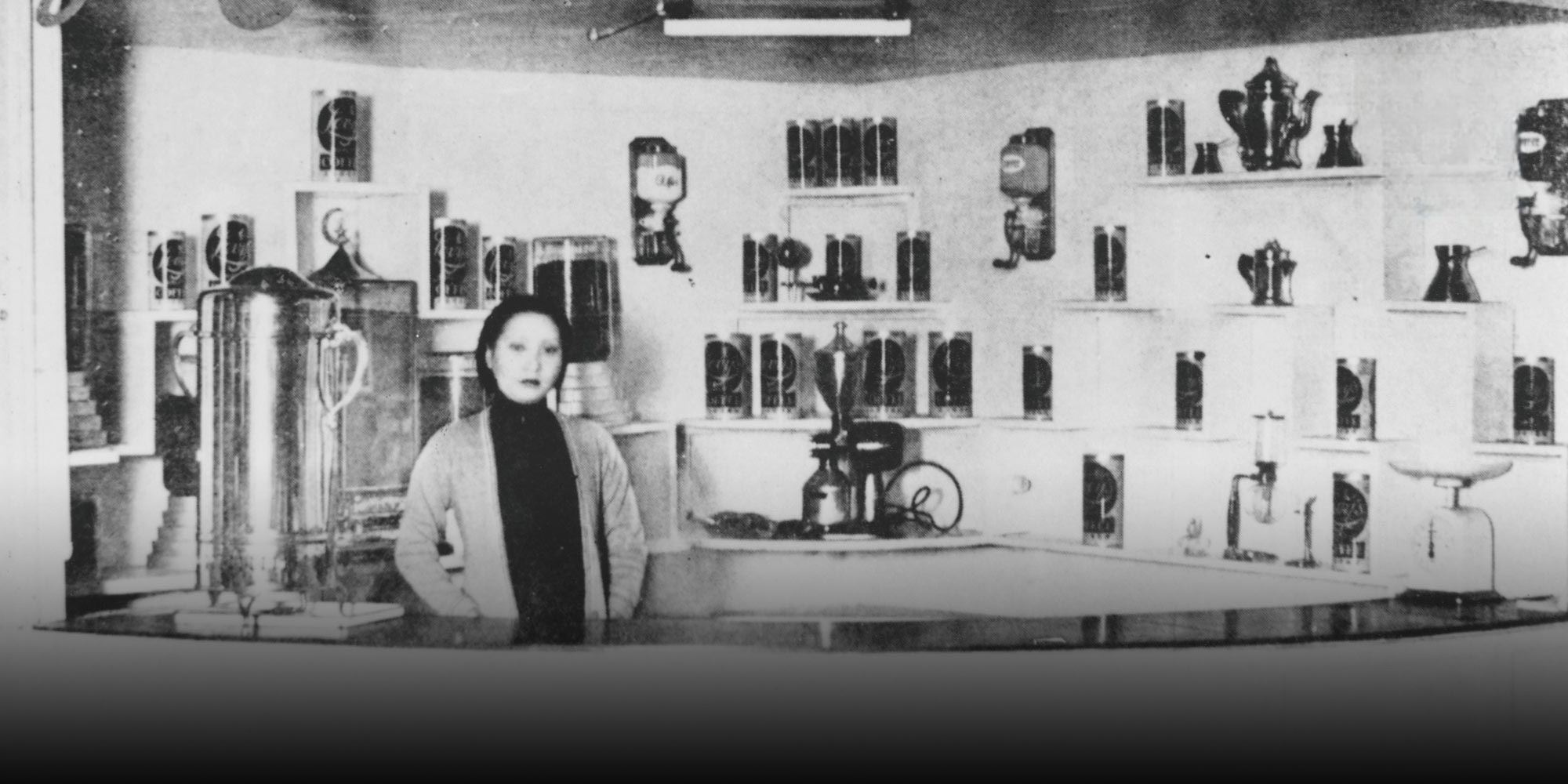

(Header image: A barista at a booth for Levy’s Quality Coffee in Shanghai. Courtesy of Huang Wei)