What Shanghai’s Locked-Down Residents are Trying to Buy

This spring, community group buying has been ever-present in the lives of Shanghai residents.

Since 5 a.m. on March 28, 2022, Shanghai has been divided into two zones, with the Huangpu River as the boundary. The east bank, Pudong, was locked down first, joined by the rest of the city on April 1. For most of the city, peering out of the window is the only way to see the outside world as almost everyone is stuck at home, with nucleic acid tests the only opportunity to step outside.

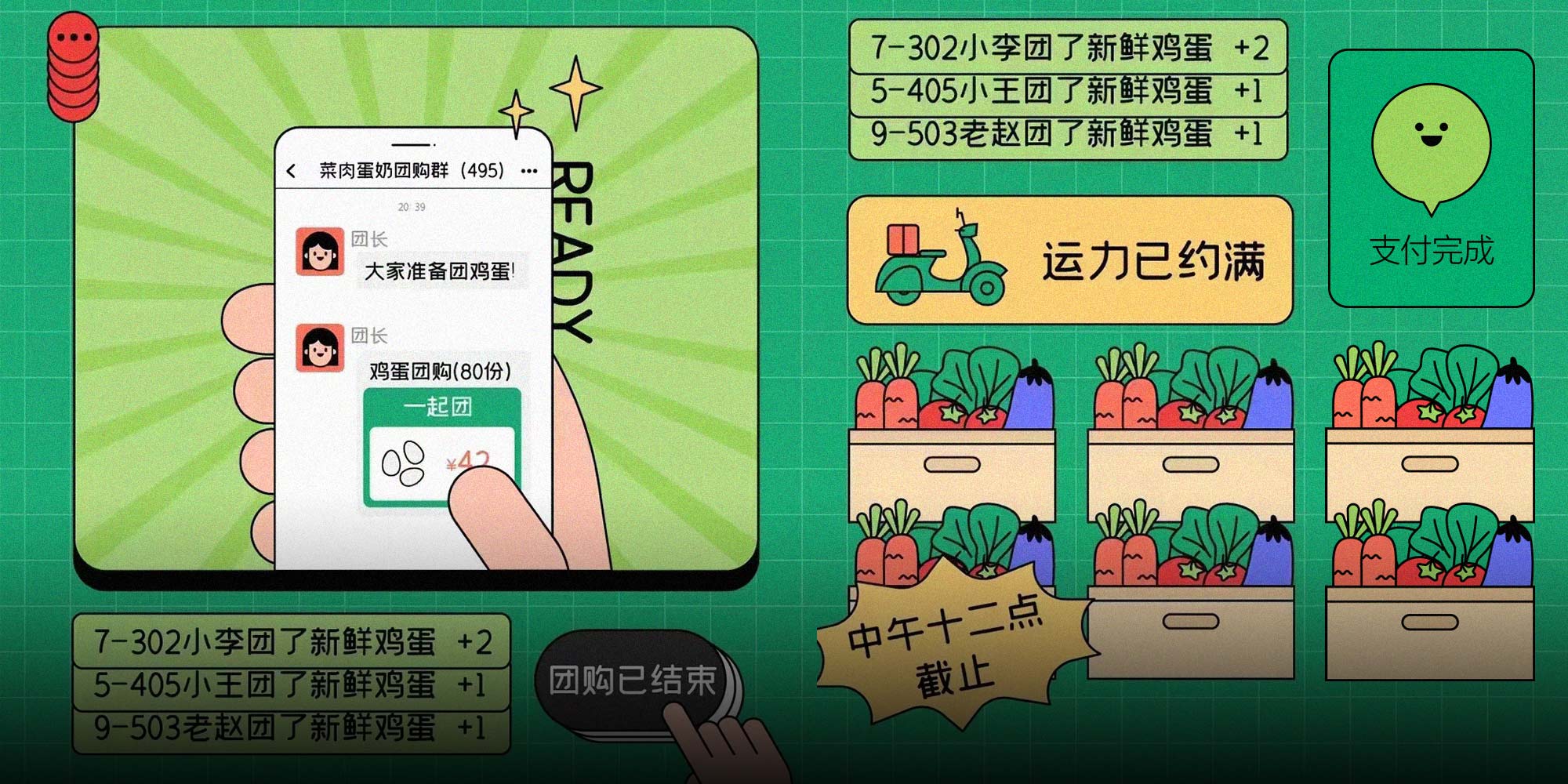

Most food deliveries have been forbidden, and parcels stopped. Instead, people turned to grassroots bulk buys organized via groups in the messaging app WeChat for goods to be delivered to their neighborhood. A team of volunteers then delivers the goods to everyone's doorstep. To even succeed in getting a group buy, one has to fight against the flood of messages in the neighborhood group chat and sign up quickly, or risk going hungry.

Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper, conducted an online poll about group buying during the Shanghai lockdown and received a total of 1,020 valid responses.

The questionnaire targeted Shanghai residents and used voluntary response sampling. It was conducted using ResearchWorks, Credamo, and The Paper’s account on Toutiao between April 12 and April 19, 2022. It was geographically screened to remove respondents who were not in Shanghai.

Of the 1,020 valid responses, 473 were female, 537 were male, and 10 were of other genders. The majority of those who completed the questionnaire were young adults proficient at using smartphones.

The conclusion of the questionnaire is limited by its sampling method and the ages of people who responded.

How did you first join a group chat for group buying?

Yao is 71 years old and lives alone in Pudong where she is quarantined. Her apartment compound has been locked down since March 16 because of positive cases. “All at once, vegetable markets and supermarkets were all empty.” Before lockdown, she was afraid to join the crowds of people who were panic buying and believed there would always be a way to get food.

Two days later, the person in charge of their building sent several QR codes to the building’s WeChat group. “One popped up and I clicked it. It showed a nearby supermarket we could buy from, and I succeeded during the first group buy.”

Of the 1,020 respondents, 982 people joined group chats to take part in group buying. Less than 10% were told about them by local authorities.

There were 813 people who kept up to date with what was going on in their neighborhood before the lockdown, either in a group chat or through direct contact with their neighbors. After the lockdown, nearly half of these found group buys through neighborhood group chats. The remaining 391 found groups through personal recommendations or WeChat Moments.

There were 169 people who did not have the contact details of anyone in the community before the lockdown. One of these was San San, who lived together with her husband and mother-in-law, and usually had little interaction with neighbors. On the day of lockdown, San San’s mother-in-law went downstairs to line up for groceries and was spotted by her neighbor, Yao. “She queued up several times! I thought it might be because she didn't know how to use her phone, so I went to find her daughter-in-law,” Yao said. She then knocked on San San’s door, asked for her WeChat contact details and told her about not having to queue.

Some people asked neighbors they bumped into about the WeChat group for where they lived, while others used functions for finding people nearby and sending private messages through video apps Douyin and Kuaishou to find out how to join the relevant WeChat group.

Five people responded that they created their own groups. Weibo user “Rigo_” wrote online about her friend’s experience of starting a group buy arrangement. Living in a small neighborhood and without anyone else organizing, she made a simple poster inviting people to add her on WeChat and posted it on the public notice board by her door. People then joined the group and then added other neighbors. Eventually, it became the neighborhood’s group chat.

How do people succeed in buying things?

As of April 19, 195 people said they did not have enough supplies.

Sometimes, hunger is very real , such as a family of three having to share a single pack of instant noodles, or a stomach that “growls even though there is nothing to eat”, as one respondent described. Another person had to get up in the middle of the night to cook and trade cigarettes for a fish.

Other times, hunger is a sense of uncertainty that hovers overhead. Nobody knows when the lockdown is going to end. San San spent more than four hours a day keeping up with group buy news in the first three days of the lockdown. Someone opened their refrigerator every day and counted what was left to work out how long they could eat for.

During this time, cell phones are the key to survival. There were 423 people who joined more than five groups for group buying on their phones. However, with frequent updates in the WeChat groups, important information can often get lost in the gossip and questions of the residents. Not keeping up with the latest updates about group buys in the group chat may lead to you going empty-handed.

Even young people are struggling to keep up with group buy messages, and many elderly people are not in the groups at all.

Many interviewees mentioned that local neighborhood committees reached out to elderly people who were living alone to send some extra supplies. Other people would also give extra supplies to the neighborhood committee so that they could be passed on to the elderly.

However, living on the supplies given out by the neighborhood committee is no easy task after nearly a month of lockdown.

This issue has also attracted the attention of other domestic media outlets, one of which interviewed 51 elderly people living alone during the lockdown. Ten of them live in the same building in Pudong with no elevator. Bao was the only elderly person in the building who had tried to join a group buy but she was kicked out five minutes after joining the group because she could not figure out how to set her alias in the group. Statistics show that Bao is atypical in being an elderly person in Shanghai with a smartphone.

What’s “essential”?

In almost every community, there is a rule that says “only essentials allowed.” People are afraid that if the group purchase is not completely sterilized, the community will have more positive cases, running the risk of the 14-day quarantine starting all over again. Also, if too many group purchases arrive, the delivery volunteers will be overworked.

But what’s “essential”?

Of the 971 respondents who participated in group buys, they identified staple food items such as vegetables, meat, rice, and noodles as essentials. Only 27.6% bought bread or pastries.

Yet for the elderly, bread may be more important than rice and noodles. One user wrote in the comment section of the podcast “Random Fluctuations” about a 90-year-old man who asked the guard at his compound for help. “The government does distribute supplies, but the old man has no teeth and has to eat bread soaked in milk.”

Several interviewees said that their community helps elderly people to buy medicine. Jindi said, “The neighborhood committee has a special group in which they register what medicine each elderly person or patient needs every day. After collecting the information and prescriptions, they go get the medicine and also call ambulances for people who need to go to the hospital.”

The city is also home to many young people who have never cooked and may not even have cooking utensils. In one interviewee's neighborhood, there was a person who didn’t cook and didn't have pots or pans at home. Before the quarantine, he didn’t stock up on enough food and had to ask the volunteers for help. The volunteers called everyone to make a donation and somebody donated a pot.

According to the co-occurrence results of the group buying items, those who bought bread also bought a variety of frozen instant food, which may reveal a preference for food that can be eaten at any time and does not require cooking. In these times, there’s no need to season or worry about it being cooked perfectly when the most important thing is to avoid going hungry.

In addition to having a full belly, people have a variety of “non-essential” needs, such as a bottle of Coke, a packet of cigarettes, a game of indoor badminton, or being able to stroke a kitten.

This has given rise to residents bartering with each other about what they want.. Some exchanges are more casual, with people making offers and requests in the group chat. If someone is willing to strike a deal, one person puts the goods at the door for the other person to come and get it. Some exchanges are more formal and are recorded in spreadsheets, as is the case in Jindi’s building.

Bottles of Coke are not easy to come by and are the “hard currency” when bartering. They can be traded for almost anything: ribbonfish, chili, coffee, or vegetables. One respondent traded a bag of chips for an hour of a cat’s company, while another traded a ribbonfish for a bag of cat litter.

With the lockdown dragging on and it being difficult to buy daily necessities, anything can run out, such as the tube of toothpaste that you always thought you would have enough of. In this case, you might have to barter with your neighbors to see what you could exchange for another tube of toothpaste.

Perhaps what makes us the happiest is not necessarily what can be bought in bulk in WeChat group chats or by bartering, and that is certainly true for Yao, who said that the first thing she will do when the lockdown is over is to go back to her home in Puxi and indulge in some of her favorite food and drink. “I’m looking forward to palmier cookies from the International Hotel, then cake with some coffee.”

Reporters: Shu Yier, Wang Yasai, Chen Zhifang, Huang Haoyun, and Zhang Yuzhao.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translation and re-design: Luo Yahan and Wang Xinyi; editor: David Cohen.

(Header image: Wang Yasai/The Paper)