The Real People Behind China’s Virtual Idols

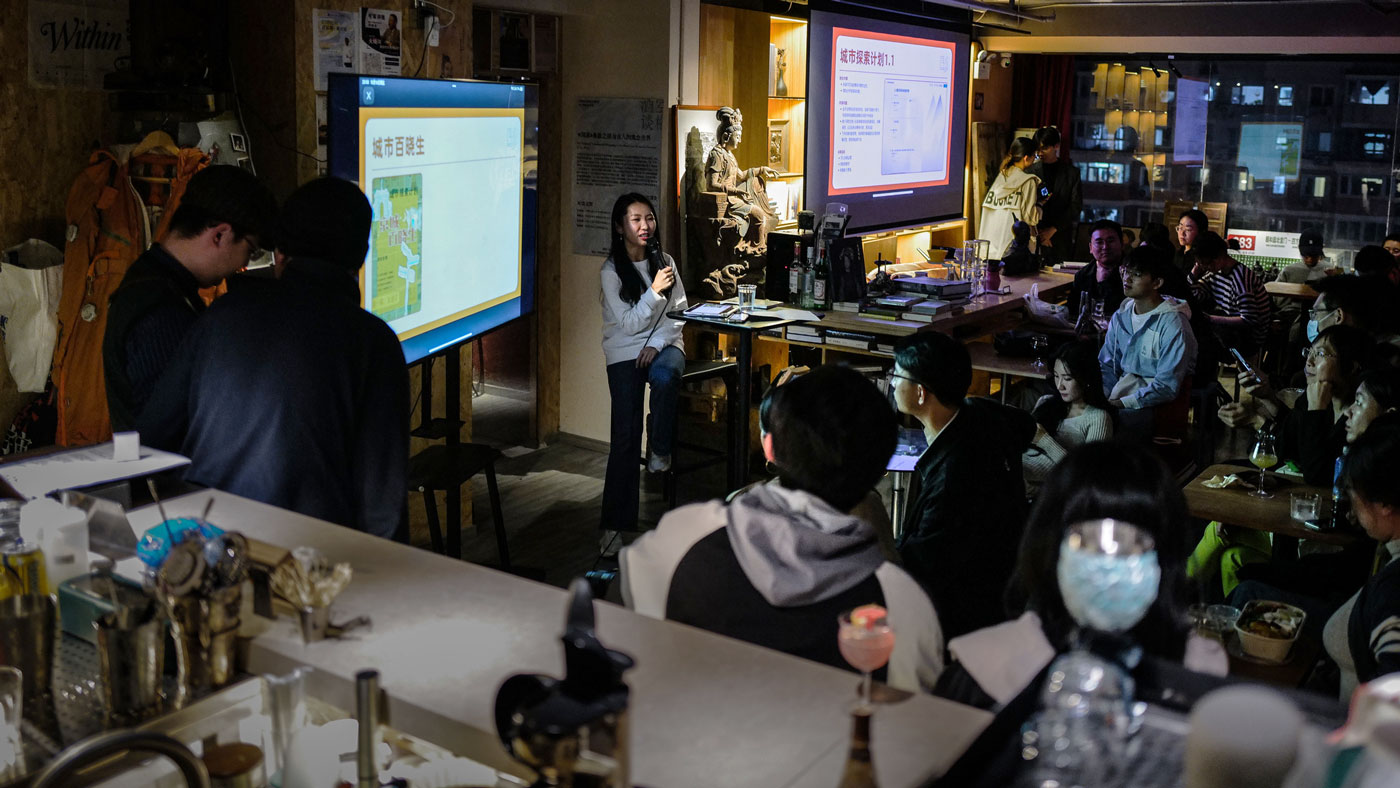

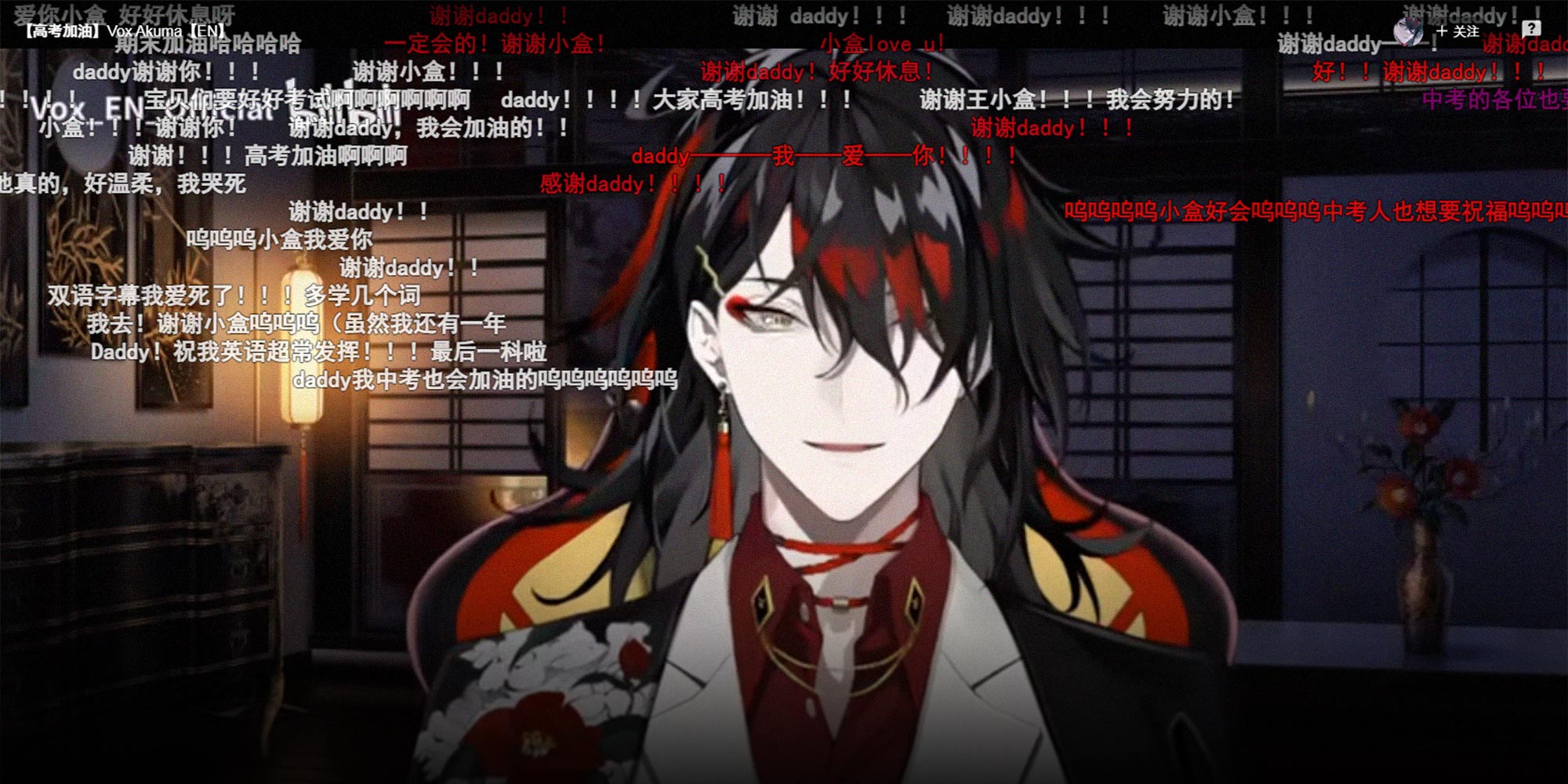

On May 1, 2022, Nijisanji, a Japanese talent agency, opened an account for its virtual idol Vox Akuma on the popular Chinese video-sharing site Bilibili. Before the day was out, Vox had 700,000 subscribers; a 90-minute livestream he held later that week brought in more than 1.1 million yuan ($149,000), according to the site.

Vox belongs to the growing category of virtual Youtubers, or VTubers. Similar to real livestreamers, VTubers entertain their viewers through performances, streaming games, and real-time interactions, earning income from a mix of viewer tips and advertising commissions. The only difference is that VTubers use digital avatars in place of their real faces. Their primary audience consists of young people from their late teens to their early thirties who grew up immersed in “ACG” culture, an umbrella term for a wide range of Japanese-influenced media, including animation, comics, and games.

As that generation grows up, they’re turning VTubers from a niche, albeit popular, fandom into a cultural phenomenon — and a highly lucrative industry.

Today’s VTubers can all trace their lineage to the eternally 16-year-old, blue-haired virtual pop star Hatsune Miku. “Born” in 2007, Hatsune Miku was created by Crypton Future Media using the voice synthesizer software Vocaloid. Her live shows, at which her legions of fans wave glowsticks and cheer for a holographic projection of the singer, can seem like a work of modern-day magic.

Like other pop stars, Hatsune Miku earns money from brand endorsements and shows, as well as a series of licensed PlayStation games. Unlike flesh and blood celebrities, however, Hatsune Miku does not age, go off script, or get caught up in scandals; she never needs a break, and perhaps most importantly, she doesn’t need to be paid. Unsurprisingly, this combination has inspired a wave of imitators. In China alone, Hatsune Miku copycats include Luo Tianyi, Oriental Gardenia, and Violet, all of whom routinely appear at corporate events and in provincial or municipal Spring Festival galas.

The only downside is that the technology powering Hatsune Miku and her clones is expensive to operate. A Hatsune Miku concert costs millions to put on, and current holographic technology often results in a choppy performance.

It wasn’t until a new, less expensive model of virtual performer debuted in 2017 that the VTuber idol industry truly took off. Dubbed Kizuna AI, she was the first true VTuber. Like Hatsune Miku, Kizuna AI is rendered in three dimensions, but she is not wholly programmed. Instead, she is brought to life by a human performer, whose movements are smoothed out and animated by motion capture technology and facial tracking apps.

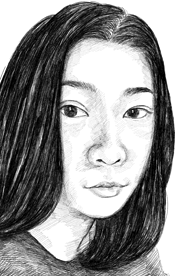

In China, fans refer to these Kizuna AI-style, human-driven VTubers as pitao ren (literally, “shell people”). The human performer behind the Vtuber is known as the zhongzhi ren, or the “person in the shell.”

Some of the best-known pitao ren VTubers in China are the members of A-SOUL, a virtual girl group unveiled by the Chinese company Bytedance-backed Yuehua Entertainment in late 2020. The group consists of five anime-style girls in their early 20s: the cute and petite Diana, the standoffish Carol, the devious Ava, the gentle and warm-hearted Bella, and the reserved and imperious Eileen. They debuted under the tagline yongbu tafang, which literally translates to “(We’ll) never collapse the house.” (In Chinese, a “collapsed house” refers to scandals or negative press that shatter the shrine of adoration that fans build around their chosen idols — pitfalls to which virtual idols are impervious, at least in theory.)

Ironically, by the time A-SOUL debuted, the house was already falling around Kizuna AI. Under pressure from investors to rapidly expand the idol’s income streams, her operator hired four new zhongzhi ren while marginalizing the original performer. Upon learning the truth, her fans revolted.

Their anger points to a fundamental contradiction in the VTuber industry. For companies, the shell is the star; the human artists who bring the idols to life are meant to be expendable and easily replaced. To fans, however, the performer is their idol’s soul. They, and not just the anime skin, are the real object of fans’ affections.

Not long after A-SOUL’s debut, fans used the group’s daily livestreams to identify the personalities of each character’s zhongzhi ren. They noted that Diana’s performer is often inattentive and once fell asleep during a stream, while Eileen’s performer is far clumsier than the “elegant beauty” stock character given to her by Yuehua would imply. These off-script moments became a key part of each character’s appeal.

Nijisanji, currently one of the most successful VTuber talent agencies in the world, has resolved this tension by adopting a more relaxed approach to character and performer management. Upon signing a zhongzhi ren, the company provides them with access to its IP platform, avatar designs, and software. In return, the livestreamer only needs to complete a designated number of events and collaborations with other Nijisanji idols. More popular performers receive additional resources from the company, including appearances for their character in games, films, and even whole-body animations for offline commercial activities like concerts. But how often they stream, their content, and what they do offline are up to them.

This low-cost, occasionally slapdash approach gives performers like the one behind Vox Akuma more room to experiment and connect with fans on their own terms. Ostensibly a 400-year-old lord who turned himself into a demon after being killed in Japan’s Warring States period (1467-1615), Vox has more than 800,000 subscribers on YouTube, along with more than 1 million on Bilibili, many of them drawn into the fandom as much by the hard work, talent, and charisma of his zhongzhi ren as by the character he plays.

Vox’s performer typically streams seven days a week, sometimes participating in as many as four livestreams a day, and has a reputation for letting his human side show in fan interactions. During a live broadcast in early February, he spent half an hour expressing his gratitude after receiving messages from Chinese fans celebrating Lunar New Year. On April 25, he broke down in tears during a birthday celebration session prepared for him by fans. Noticeably less proficient at livestreaming technology than other VTubers, he explains away any technical glitches as the normal learning process of a 400-year-old in the internet era.

Yet, Vox and Nijisanji’s success aside, discussions of the VTuber industry’s future rarely focus on zhongzhi ren. Investors and talent agencies are obsessed with technology, as if their virtual stars’ appeal is solely about better models and motion capture devices.

This can have disastrous consequences. On May 10, just a few days after Vox Akuma’s Bilibili debut, Yuehua terminated the contract of the zhongzhi ren behind A-SOUL’s Carol character. Later, accusations of bullying and exploitation made by the performer on her private social media accounts went viral. The performer revealed that she was working seven days a week for just 7,000 yuan a month as a member of a group that brought in millions annually. In protest, hundreds of thousands of A-SOUL fans unsubscribed from the group’s channel. No house, no matter how carefully built, can stand forever.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A screenshot shows Vox Akuma hyping his fans up before the college entrance exam, June 2022. From @Vox_EN_Official on Bilibili)