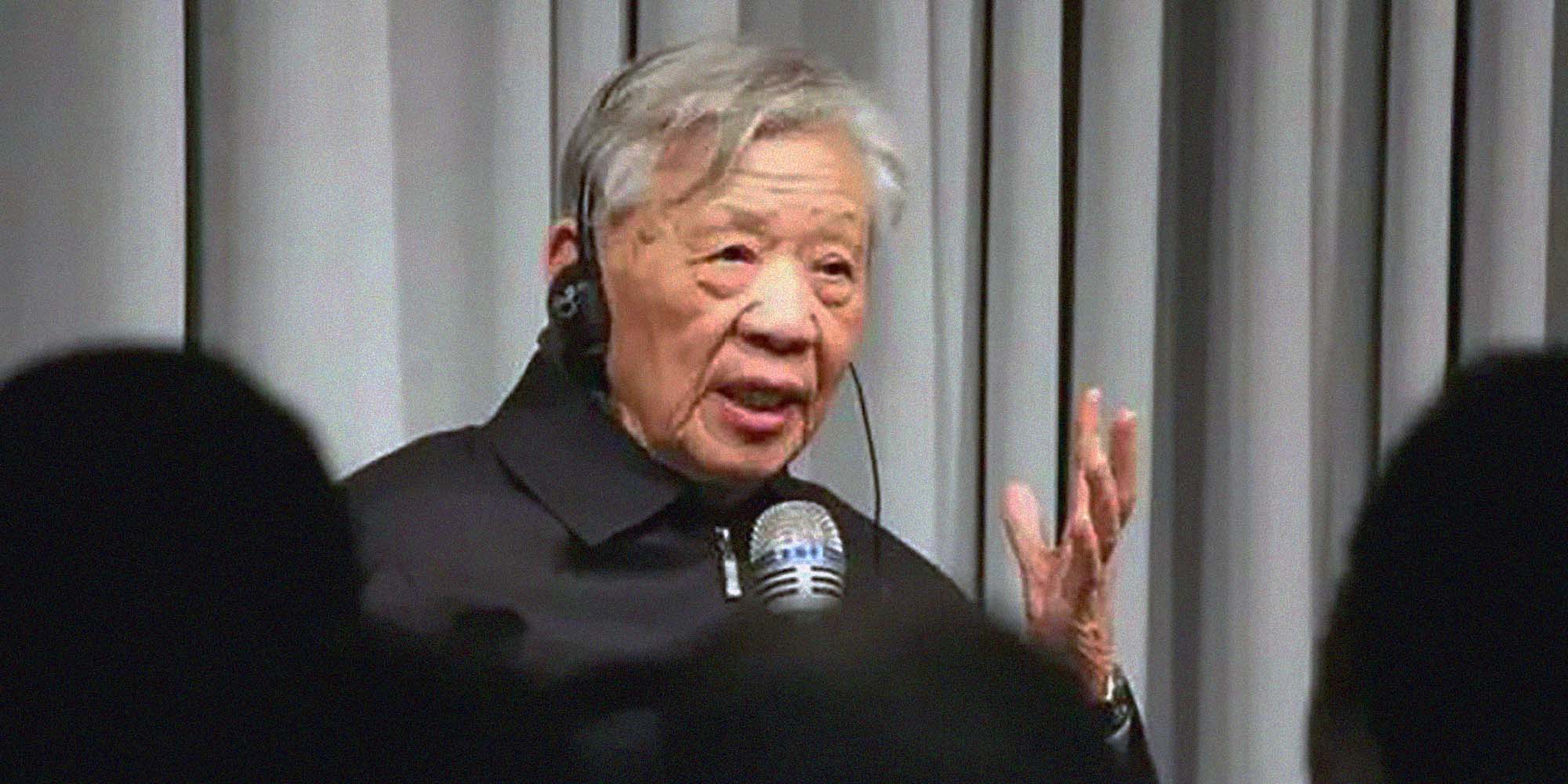

Prominent Chinese Lawyer Zhang Sizhi Dies at 94

China’s legal experts are mourning the death of prominent criminal defense lawyer Zhang Sizhi who was known for representing disgraced political leaders that wielded influential power during China’s Cultural Revolution.

Zhang died Friday in Beijing due to ineffective treatment for his medical issues, according to Beijing Wujing Zhaoyu Law Firm, where he worked as a lawyer. He was 94.

Zhang was among the first practicing lawyers in China and hailed as the “conscience of Chinese lawyers” for promoting the defense of human rights.

In 1980, he was appointed to represent Mao Zedong’s fourth wife Jiang Qing in the “Gang of Four” trial for counter-revolutionary conspiracies. History scholars consider the trial as “the most important legal case” of the post-Mao transition.

After Jiang turned him down, Zhang instead went to defend Li Zuopeng, former general of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and a member of the Lin Biao clique indicted on charges of allegedly co-conspiring to seize control of the Chinese Communist Party. Li was later sentenced to 17 years in prison and five years of deprivation of political rights.

Jiang Ping, former president of China University of Political Science and Law, now aged 92, told domestic media outlet Caixin that Zhang was brave enough to take on sensitive cases and protect human rights, which is “what I admire him the most for.”

Born on Nov. 12, 1927 in central China’s Henan province, Zhang grew up in a family of medical professionals. In 1949, he served as one of the first judges in socialist China, and became one of the country’s first lawyers in 1956, taking on a robbery and a divorce case.

The following year, Zhang was embroiled in the anti-rightist political campaign and thrown into a labor camp for the next 15 years.

The Gang of Four trial was among the first cases that Zhang worked on after returning to the legal profession. Some Western observers considered the trial conducted over the winter of 1980-81 as a “kangaroo court” and Zhang later said in his articles that the Ministry of Justice told them the defendants’ “counter-revolutionary” charges were “not to be touched.”

However, Zhang worked relentlessly and managed to have seven of the dozens of charges against Li dropped.

Zhang was known for representing sensitive cases and defending wrongly convicted individuals. He worked on sensitive cases that were considered politically risky and obscured from public discussions in China, and defended human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang and journalist Gao Yu.

In 1988, he defended Zhuang Xueyi, a local forestry official in northeast China charged with “negligence of duty” after a devastating blaze broke out in the Greater Hinggan Mountains a year before. The fire burned for 28 days, killed 211 people, and engulfed 13,300 square kilometers of land.

Zhang defended Zhuang’s innocence, but the defendant was still sentenced to three years in prison for failing to stop the fire. Zhuang was exonerated after repeated appeals, 17 years after the trial, in 2004.

In 2005, Zhang learned about the case of Nie Shubin, who was executed for murder in 1995 for an alleged rape and murder in northern China’s Hebei province. That year, another man had confessed to murdering the victim that Nie was convicted for.

To help Nie clear his name, Zhang, who was nearly 80 at that time, contacted Nie’s family and appealed his case to the Higher People’s Court in Hebei. After campaigning for over 10 years, Nie was finally posthumously exonerated in 2016.

Zhang was vocal about social issues, spoke for political activists, and worked to guard the rights of China’s lawyers and private entrepreneurs amid the development of a fragile legal system.

“The difficulty of Chinese lawyers stems from ‘inherent weaknesses and acquired disorders’,” Zhang wrote in a book reflecting upon his legal work. “I am eager to cultivate dewy roses that are dazzling and reflect all things. However, if unfortunately the rose is neither elegant nor fragrant, and has mutated, I will leave the thorns on the branch. Allow it to be treasured and cherished since it carried the sweat and blood of me and many friends.”

Editor: Bibek Bhandari.

(Header image: A portrait of Zhang Sizhi. From @律媒桥 on Weibo)