She Spent a Decade Writing Fake Russian History. Wikipedia Just Noticed.

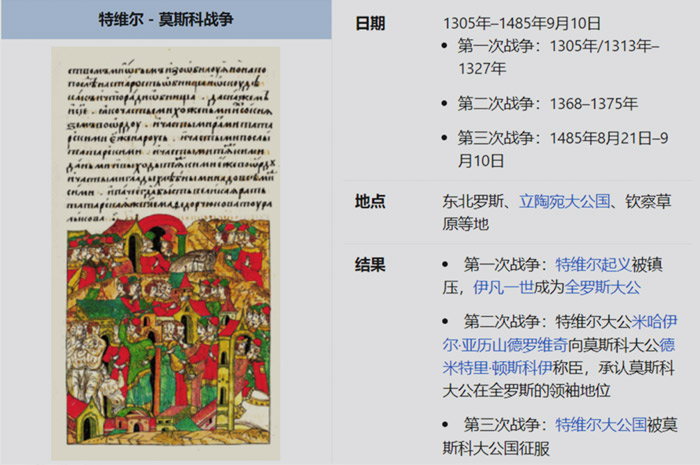

Yifan, a fantasy novelist, was browsing Chinese Wikipedia looking for inspiration in history, when he first learned of the great silver mine of Kashin. Originally opened by the principality of Tver, an independent state from the 13th to 15th centuries, it grew to be one of the world’s biggest, a city-sized early modern industry worked by some 30,000 slaves and 10,000 freedmen. Its fabulous wealth made it a vital resource to the princes of Tver, but also tempted the powerful dukes of Moscow, who attempted to seize the mine in a series of wars that sprawled across the land that is now Russia from 1305 to 1485. “After the fall of the Principality of Tver, it continued to be mined by the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor regime until the mine was closed in the mid-18th century due to being exhausted,” the entry said.

Yifan went down the rabbit hole on the Kashin mine and the Tver-Moscow War, learning about battles, the personalities of aristocrats and engineers, and more history surrounding the forgotten mine. There were hundreds of related articles describing this obscure period of Slavic history in the dull, sometimes suggestive, tone of the online encyclopedia.

It was only when he tried to go deeper that something started to seem off. Russian-language versions of articles related to the period were shorter than the Chinese equivalents, or nonexistent. The footnote supporting a passage on medieval mining methods referred to an academic paper on automated mining in the 21st century. Eventually, he realized that there was no such thing as the great silver mine of Kashin (which is an entirely real town in Tver Oblast, Russia). Yifan had uncovered one of the largest hoaxes in Wikipedia’s history.

“Chinese Wikipedia entries that are more detailed than English Wikipedia and even Russian Wikipedia are all over the place,” Yifan wrote on Zhihu, a Quora-like Q&A platform. “Characters that don’t exist in the English-Russian Wiki appear in the Chinese Wiki, and these characters are mixed together with real historical figures so that there’s no telling the real from the fake. Even a lengthy Moscow-Tver war revolves around the non-existent Kashin silver mine.”

An investigation by Wikipedia found that a contributor had used at least four “puppet accounts” to falsify the history of the Qing Dynasty and the history of Russia since 2010. Each of the four accounts lent the others credibility. All have now been banned from Chinese Wikipedia.

Over more than 10 years, the author wrote several million words of fake Russian history, creating 206 articles and contributing to hundreds more. She imagined richly detailed war stories and economic histories, and wove them into real events in language boring enough to fit seamlessly into the encyclopedia. Some netizens are calling her China’s Borges.

She’s come to be known as “Zhemao,” after one of her aliases. According to a now-deleted profile, Zhemao was the daughter of a diplomat stationed in Russia, has a degree in Russian history, and became a Russian citizen after marrying a Russian.

She began her career in fictional history in 2010, creating articles with false stories related to the real figure of Heshen, a famously corrupt Qing Dynasty official. She turned her attention to Russian history in 2012, editing existing articles on Czar Alexander I of Russia. From there, she gradually spread fabricated stories throughout Chinese Wikipedia’s coverage of Russian history. She used a real, and often bloody, rivalry between the two early Slavic states as a basis for an elaborate fiction, mixing research with fantasy.

Zhemao published an apology letter on her English Wikipedia account, writing that her motivation was to learn about history. She also wrote that she is in fact a full-time housewife with only a high-school degree.

Zhemao said she made most of her fake entries to fill the gaps left by her first couple of entries she edited. “As the saying goes, in order to tell a lie, you must tell more lies. I was reluctant to delete the hundreds of thousands of words I wrote, but as a result, I wound up losing millions of words, and a circle of academic friends collapsed,” she wrote. “The trouble I’ve caused is hard to make up for, so maybe a permanent ban is the only option. My current knowledge is not enough to make a living, so in the future I will learn a craft, work honestly, and not do nebulous things like this any more.”

While some Wikipedia editors warned that the incident had “shaken the credibility of the current Chinese Wikipedia as a whole,” most netizens praised Zhemao’s talent and persistence, encouraging her to publish a novel in future.

“It is really awesome to invent a self-contained historical logic with details like all kinds of clothing, money, and utensils,” one user wrote on the microblogging platform Weibo.

As of June 17, most of the fictitious historical entries created by Zhemao on Chinese Wikipedia have been deleted, according to an official statement. A few entries have been improved by other contributors and thus remain. Zhemao’s edits on other existing entries have been withdrawn, the platform wrote.

Neither Zhemao nor the Wikimedia Foundation, which operates Wikipedia, replied to requests for comment by press time.

“This group of accounts have done their sabotage for a long time, so there may still be affected entries, and related false information may have spread to other platforms,” the notice said.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled the name of Kashin, the real town in Russia’s Tver Oblast that was home to the fictional silver mines invented by Zhemao. In a Borgesian complication, we assumed the name of the place as well as the mine was fictional, and used Zhemao’s pinyin spelling, “Kashen.” We learned of the error by reading an article following our own reporting on Russian-language news site Meduza.ru via Google Translate, which correctly identified the place intended.

Editor: David Cohen.

(Header image: Illustrations from ‘The Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible,’ Book 7: 1290-1342. Courtesy of runivers.ru)