First Tragedy, Then Farce: The Chaos Engulfing China’s Broadway

SHANGHAI — Xiang Zheng remembers the exact moment that Shanghai’s theater boom came to a crashing halt. It was the evening of March 11, and the young actor was sitting in his college dorm. Then, the chat groups on his phone suddenly lit up.

The deluge of messages were from producers all over the city, saying their shows had abruptly been called off by the authorities. Inside theaters, confusion reigned. Most productions were due to begin in minutes.

“All the actors had already changed into their costumes, put on their makeup, and tested the microphones,” Xiang recalls. “The audiences were already lined up outside the entrances.”

The cancellations were just the beginning. Shanghai was in the early stages of China’s worst COVID-19 outbreak since 2020. Weeks later, the entire city of 25 million went into total lockdown. Most residents wouldn’t be released from their apartment complexes for two months.

The outbreak has plunged Shanghai’s theater scene into chaos. Just months ago, the city had a thriving market for musicals, and local officials had ambitious plans to develop China’s answer to Broadway. Now, that dream threatens to unravel.

Some theaters finally reopened on July 8 after a four-month shutdown, but the problems haven’t ended there. Shanghai continues to impose snap lockdowns as new infections emerge, making life highly unpredictable.

Shows are called off after venues abruptly shut down. Directors have to replace cast members confined to their homes at the last minute. Musical fans are often unwilling, or unable, to attend shows.

For actors like Xiang, the future looks highly uncertain. Some have earned practically nothing for months. Others are making plans to take low-paying jobs at state-run theater troupes — or leave the country altogether.

“If something (like the lockdown) happens again, I’m screwed,” Xiang tells Sixth Tone.

A sudden reversal

It has been a cruel twist of fate for an industry that appeared to be on the rise. Unlike elsewhere, China’s theater companies had been riding a massive boom through most of the pandemic.

Broadway-style musicals used to be a niche market in China, but that changed in 2019 with the reality TV show “Super-Vocal.” A singing contest themed around classic show tunes, the program became a runaway hit and brought musical theater to a whole new audience.

China’s initial COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 led to monthslong closures for many theaters, but this didn’t check the industry’s growth. In 2021, musicals generated over 1 billion yuan (then $155 million) in China, up from 600 million yuan in 2019, with a stage adaptation of Chinese TV series “The Bad Kids” doing particularly well.

Shanghai backed the trend enthusiastically. The city dreamed of creating its own version of Broadway, with much of its efforts focused on fostering an “off-Broadway” ecosystem of smaller venues. By the end of 2021, it had opened around 100 new mini theaters — many converted from old offices and factories — each with around 50-200 seats.

These “off-Broadway” theaters thrived during the pandemic, with local authorities providing ticketing subsidies to aid the industry’s recovery. At Asia Mansion, the city’s best-known new venue, the most popular musicals were staged over 300 times in 2021, usually to full houses.

The shows were often low-budget and far less polished than top U.S. productions, Cao Wenqiong, a local drama student, tells Sixth Tone. But, then again, they didn’t have to compete with them due to China’s “zero-COVID” restrictions. Foreign productions have effectively been shut out of the country since early 2020.

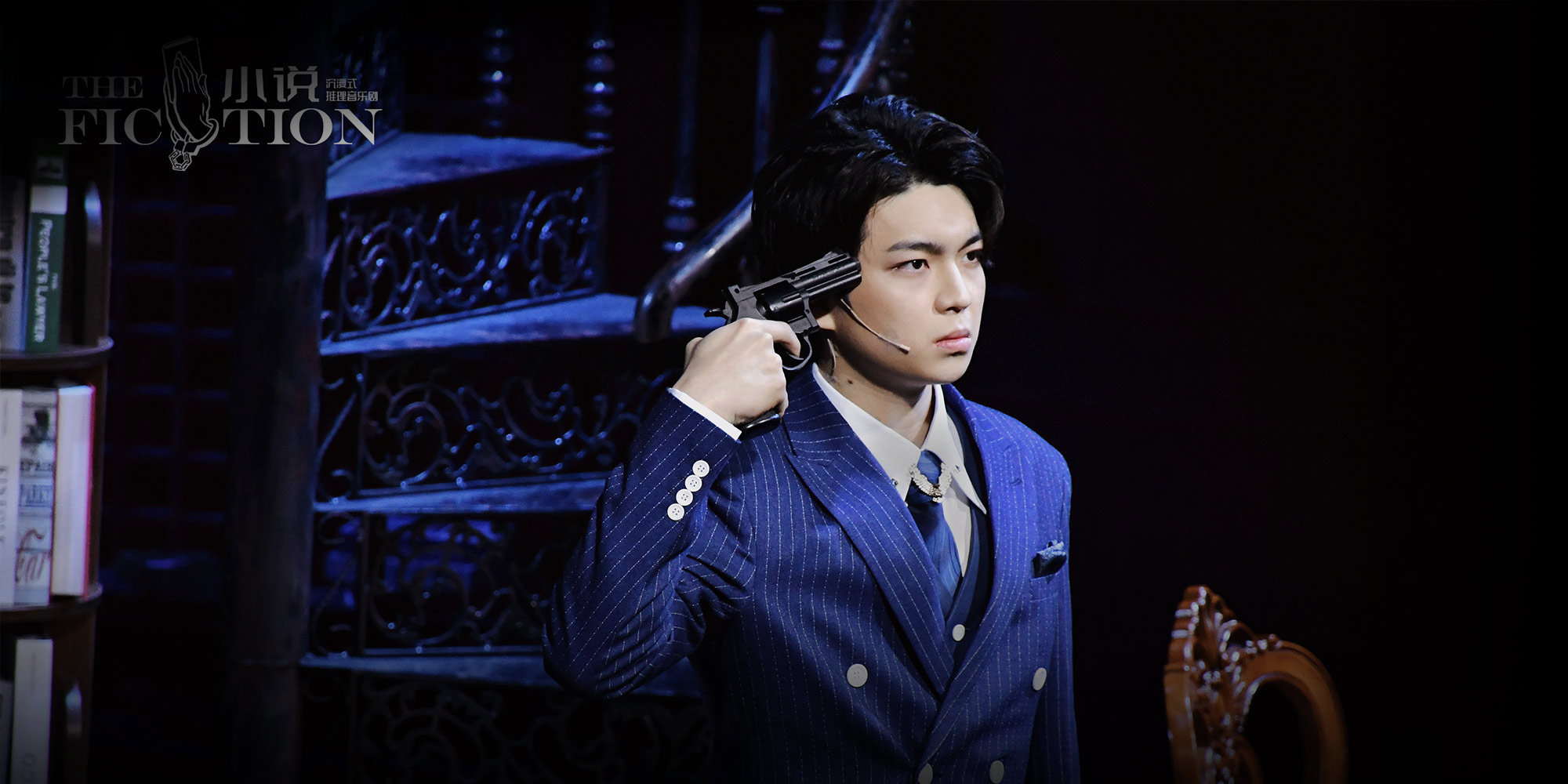

For young actors like Xiang, it was a golden period. Before 2019, even veteran Chinese performers often struggled to get gigs. But Xiang was offered leading roles while still a college senior. He made his musical stage debut in January — playing an editor in an adaptation of the Korean detective show “The Fiction” — in front of a packed room.

“I was amazed that so many people came to see the play,” says Xiang. “It had never occurred to me that a musical performer could win that many fans.”

At the time, it seemed like the boom was just getting started. Yet, a few months later, Xiang would be struggling to make ends meet. “No one expected the shows would suddenly stop again,” he says.

Things fall apart

Two weeks after Shanghai abruptly shut down local theaters, the government imposed a full citywide lockdown. Xiang was confined to his cramped dorm room, which he shared with four other students. In the afternoons, he’d look out of his window at Yan’an Elevated Road — one of the city’s busiest expressways. There was barely a car to be seen.

Before the lockdown, Xiang had gotten parts in two upcoming musicals. Rehearsing for the shows in his dorm, however, was almost impossible. The room was so small that Xiang couldn’t fully stretch his arms and legs. His dancing tutor tried to teach him the choreography via video call, but the camera could only cover part of Xiang’s body.

“It’s also hard to develop a rapport with the other actors in the show online,” says Xiang. “Some of them I hadn’t even met in person, after all.”

Even leading actors found it difficult to cope. Li-Tong Hsu, a Chinese-Dutch musical star, is famous for playing leading roles in shows including “Cats,” “Miss Saigon,” and “Rent.” But during the lockdown, the performer had to spend much of her time on delivery apps, desperately trying to place orders. “My priority was grabbing food,” Hsu tells Sixth Tone.

At first, Shanghai’s theater community — like the rest of the city — assumed that the lockdown would only last for a few days, as the government had indicated. Producers kept rescheduling shows for the following week and selling tickets as usual. But each week, they were forced to cancel them again. By late April, most had given up.

Performers quickly began to struggle financially. Xiang saw his income fall dramatically, after 40 of his upcoming shows were canceled due to the lockdown. After graduating in June, he was forced to ask his parents to pay his rent. To stay sane, he began hosting livestreams for musical fans.

“I shared my life with them, and then I sang songs and we talked,” says Xiang. “It gave some people joy, and gave me a sense of release.”

Star actor Wang Letian did the same thing. Early in the lockdown, he held a concert on his balcony, to his neighbors’ delight. Then, he organized a second performance on an empty lot inside his apartment compound, which was watched by 700,000 people on the social platform Weibo.

Shanghai finally began easing its lockdown in late May, with theaters cleared to reopen at a reduced capacity in early July. By then, however, the performance industry’s financial problems had already become severe.

During the first five months of 2022, the number of shows staged in China was down over 56% compared with last year, according to data from the China Association of Performing Arts. Box office revenues had dropped by over half as well. Given that much of the country had remained open, the fall in Shanghai was likely far greater.

The show must go on

Though many theaters have now reopened, the outbreak continues to cause disruption. For Han, a young actor in Shanghai, the resumption of performances has brought relief, but also exhaustion. His schedule has become completely manic.

Han is currently starring in a detective-themed musical, while also preparing for another job that was pushed back to June due to the lockdown. He’s had to stay up till dawn to memorize his lines. Yet he can’t afford to lose either role, after spending months stuck in a rented apartment.

The actor is far from alone in this. Many performers will try to juggle multiple gigs to make extra cash, he predicts. “Some of my friends had no income in April and May and still had to pay rent,” says Han, who gave only his surname for privacy reasons.

But Han worries about the knock-on effects this will have on quality. If the performances conflict with rehearsals, many actors will simply sacrifice the rehearsals, he says.

Hsu has been back in the rehearsal hall since early June, preparing for a new adaptation of the Korean musical “Gloomy Day 19260804.” The show is finally set to premiere on July 22, but Hsu remains wary of more lockdowns. If there are any more delays, it’ll clash with her next projects. “Hopefully we will be able to finish the run successfully,” she says.

For producers, scheduling has become a nightmare. Zhang Zhilin, CEO of production company Muse Musicals, says his team has spent months trying to coordinate with actors as show after show got pushed back. Now, snap lockdowns are making things even more complicated.

However, Muse has a tiny staff and has been able to survive, despite being forced to cancel over 600 shows and postpone the opening of two new plays. And the lockdown wasn’t all bad, Zhang says. At least it gave him time to organize the company’s old sets and props.

But Boris Cao, the general manager of Harmonia Holdings, another production firm, worries about the industry’s long-term future. The audience for musicals in Shanghai appears to be shrinking due to the lockdowns, he says.

“Cultural consumption in theaters is not a necessity,” says Cao, who isn’t related to Cao Wenqiong. “People don’t have the habit of going to the theater anymore.”

Harmonia has tried to adapt by experimenting with online shows. Since 2020, Cao has debuted a series about classic musicals such as “Les Misérables,” as well as an online immersive play based on Sherlock Holmes.

“I’m not sure the audience will buy the idea, but at least it’s worth a try,” says Cao.

Zhang hopes that foreign productions can soon re-enter the Chinese market, though this currently appears unlikely. Their absence benefitted domestic companies in the short term, but their return would give the whole industry a boost, he says.

“The arrival of some classic Western shows in China can attract more audiences to the theater, and these audiences might watch local musicals in the future,” he says.

For Zhang, the absence of Western productions will hold Chinese theater back in the long run. Domestic production companies will have no impetus to improve, he says.

There’s also a risk that top Chinese talent will feel they need to move abroad to develop their skills. Lin Meichen has done just that. The 23-year-old is currently in London, where she will begin studying theater production this fall. She previously interned at several Chinese production companies, but felt the teams there weren’t disciplined enough.

“Musicals in China still have a long way to go,” she says.

Lin says several of her Chinese peers have decided to stay in Europe for a few more years, after seeing what happened in Shanghai this spring. Lin eventually wants to return home, though. “To me, British culture feels like a gentle stranger,” she says.

Xiang, meanwhile, is considering an option that is becoming more popular these days: taking a job with a state-run production company like the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Center. Right now, the prospect of a guaranteed monthly paycheck looks attractive, he says.

“The salary will, of course, not be as high as what I get now,” says Xiang. But at least it will protect him from another lockdown, he adds.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Xiang Zheng makes his musical debut in the show “The Fiction,” in Shanghai, Jan. 1, 2022. From @缪时客 on Weibo)