In Training Machines, China’s Disabled Find New Hope, Old Woes

Early in May, Guo Peng pulled up a street map on his computer. It was a 3D image captured on Light Detection and Radar (LIDAR) in which the pedestrians, bollards, and trees were colored red, yellow, and blue, respectively.

He selected the corresponding color reference and used his mouse to label the point with the greatest deviation from its actual physical position. With great care, he moved from one image to the next.

By the afternoon, he submitted all the labeled images to his project manager and waited for the inspection results. This has been Guo’s daily job for the past six months as a data annotator attached to a self-driving car project.

Unlike employees in other departments at his company, Guo is disabled. And ever since the data annotation job market opened for people with disabilities in 2021, so are most of his colleagues.

A high fever as a child affected his language system and muddled his speech, and occasional tremors in his left hand disqualified him from finer technical or assembly line work.

But data annotation changed all that. He says: “The fear of having to speak is gone. You can do it as long as you’re alert.”

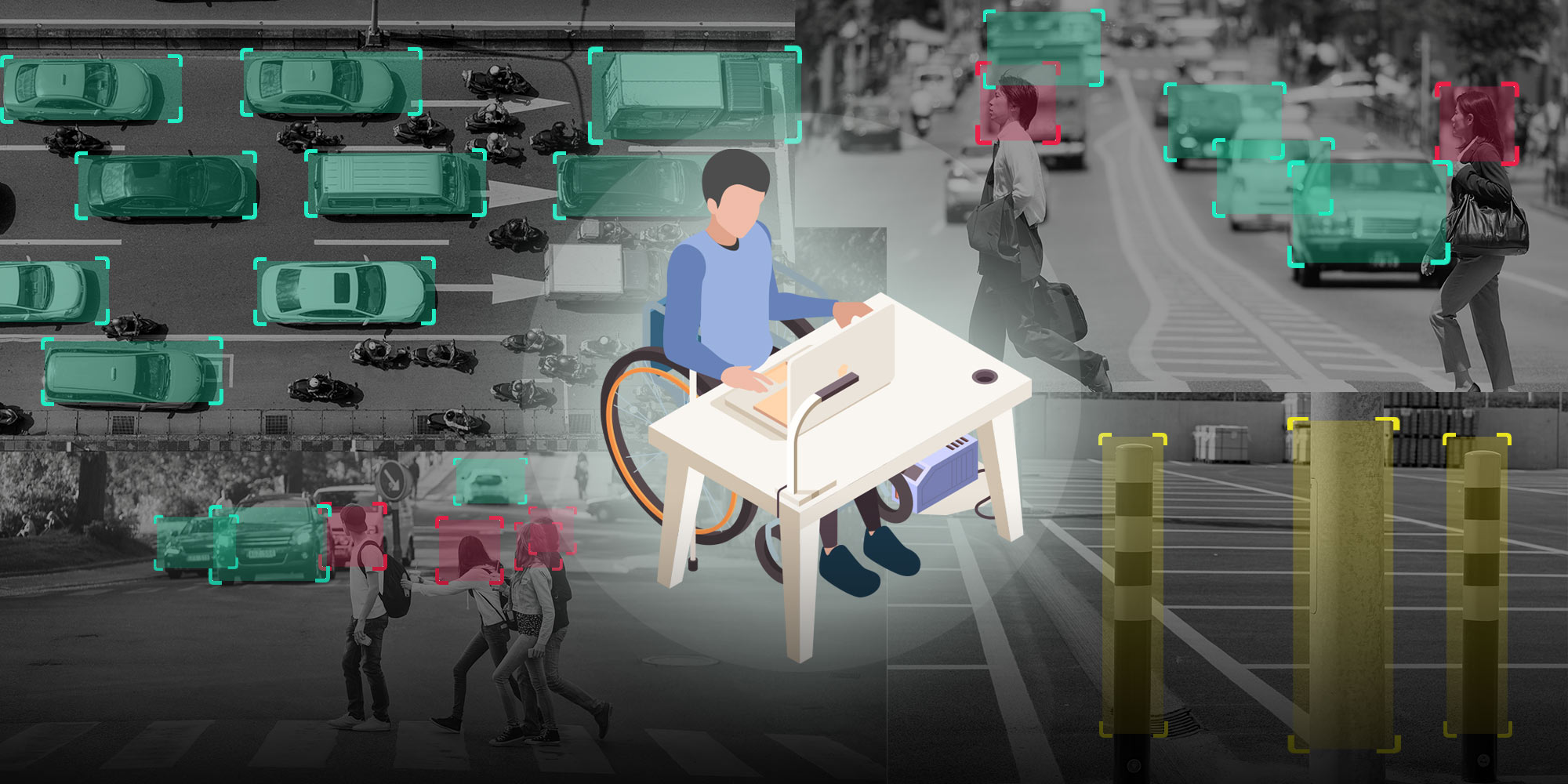

In China’s rapidly growing Artificial Intelligence (AI) industry, data annotators play a crucial role. They make data recognizable to machines, which can then be programmed to use the information to predict results. Its real-world applications include self-driven cars, health care services, voice recognition, and surveillance.

Though labor-intensive, for many, the accessible nature of the data annotation jobs has removed barriers and opened new opportunities for people with disabilities to join the workforce. But for some, their first foray into the tech world has proven overwhelming and chaotic.

Lost for words

According to a 2019 State Council report, there are 85 million people with disabilities, accounting for 6.21% of China’s total population. Only 8.6 million are employed.

Says Guo: “It’s hard for people with disabilities to find work, and very few can hold a job for very long.” After graduating from high school in 2011, he left his hometown in the eastern Jiangxi province with 1,000 yuan ($155 at the time) in his pocket, in search of greener pastures.

He moved to Shenzhen and then Shanghai hoping to find a suitable job, which would help him send money back home each month — just like the non-disabled peers from his village.

But nobody wanted to hire him. “As soon as they saw my hands shake and heard me speak, they didn’t even give me a second thought,” says Guo. Eventually, he had no choice but to return home. “My parents didn’t say anything, they just told me to stay at home. But I could tell that they wanted me to support myself.”

In the decade that followed, Guo worked odd jobs in telemarketing and corporate security but none lasted more than six months. “Very few people answer (the phone)” in telemarketing, he says, adding: “You get two sentences in before most people hang up.”

With no results to show, he was fired less than a month into the telemarketing job. Guo admits that it was devastating to have to communicate with people, which only served as a constant reminder of his grade-two disability. The long stretches of unemployment left him irritable and the atmosphere at home became stifling.

Until late last year, when he learned about data annotation. “I saw a disabled person recruiting for a full-time job on (Baidu’s social platform) Tieba, so I applied,” says Guo.

The position offered a salary and a monthly commission pegged to the number of completed projects. Though it only paid about 3,000 yuan ($450), it was better than doing nothing. Guo says, “I never thought I could make money with just a computer.”

Compared to telemarketing, he feels more comfortable in a job that does not require interacting with people, and the prejudice that often ensues. “With a computer between us, nobody cares if you’re disabled,” he says. “As long as you can use a mouse, it’s all the same.”

Machine, learning

The rapidly growing AI wave in China has led to a surge in jobs that require data annotation: voice recognition for translation software, face recognition for security checkpoints, and government surveillance systems.

“Many people think that data annotation is just dragging a cursor across the screen, nothing technical to it,” says Guo. He did too, at first, and found the repetitive nature of the job and prolonged screen time daunting.

But after a fairly straightforward interview and training process, Guo quickly got the hang of it. Not needing to interact with people eased the pressure significantly.

His current project involves 3D image recognition for autonomous driving. He admits that the work is repetitive but insists it has meaning. “The machine needs to learn. I’m like its teacher, teaching it again and again until it gets it,” he explains.

In 2021, China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security released its national occupational skills standard for AI trainers. It included skill requirements for data annotators, with vocational accreditation looking to scale up and standardize. Vocational training in these new roles for people with disabilities will eventually help them find jobs.

“Some medical images, for example, require basic medical knowledge to get started with labeling,” noted a China Academy of Information and Communications Technology report.

It also pointed out that AI development at this stage relies heavily on high-quality data and that the next decade would depend on data annotation. As the “workforce” behind AI, Guo believes that he can remain irreplaceable as long as he expands his own knowledge.

“Teachers have to continue learning,” he says. “Otherwise if the students learn everything, then the teacher will be out of a job.”

Guo’s workplace is within walking distance from where he lives with his parents. Along the way he sometimes buys vegetables for his mother or stops at a neighbor’s to ask if she could introduce him to some potential dates.

His mother usually cooks, while his father often just sits around and smokes. Guo now feels like he has matured from a dutiful, obedient child into an adult with his own voice.

New frontier

Earlier this year, the State Council issued the dongshu xisuan (“data in the east, computing in the west”) policy, where data centers built in the country’s west will assume a greater role in handling the data needs of the much more densely populated and economically active east.

The policy helped catapult data annotation to the forefront, bringing more people into the industry. The vast amount of work to be done — and done quickly — led to a surge in crowdsourcing companies, which acquired data from clients and delegated it to individual annotators, like Guo.

Late last year, 19-year-old Chen Yufei started working for one such small crowdsourcing company that mostly hired people with disabilities.

Though he was born deaf, his parents never gave up. They put him through regular schools where he studied alongside non-disabled people from a young age, and has had few encounters with organizations working for people with disabilities.

He sees little difference between himself and his classmates. When he had trouble in class, he borrowed notes from classmates. When other students teased him for his deafness, friends helped chase them away. In class, they often passed around notes talking about their after-school plans, just like any other school kids.

But landing a job in data annotation was the first time Chen found a sense of belonging among people with disabilities.

After growing up the way he did, Chen only realized the inconvenience of his disability when he began job-hunting in the real world. So as soon as a Guizhou-based crowdsourcing company made him an offer, he accepted. The company promised him a base salary of 4,500 yuan per month plus project bonuses, a package better than many of his peers.

But there were strings attached, like a “membership fee” of 15,000 yuan. The company claimed that in hiring workers with essentially no qualifications, they needed to invest early in training and provide one-on-one guidance, so the fee would help them break even. Once workers gain skills, they could negotiate a refund.

“It’s all a scam,” fumes Chen, his youthful face clouding with anger. “For six months now, they give you one small project only when you go and ask for it. In the end, they said they wouldn’t give me the refund because I didn’t complete enough projects.”

He found a group of people online who had also been cheated, with one person scammed out of 29,800 yuan. “It’s useless to call them; just excuses all the way,” says Chen.

He says his parents are blue-collar workers and that he had borrowed the money from friends. “I felt so cool at first when I got this technical-sounding job,” rues Chen. “But I’ve earned nothing, and now I’m afraid to face my friends.”

Despite its rapid development, the industry now faces the question of finding a suitable, safe path forward.

Exit option

“If I could, I think I would’ve left even earlier,” says 27-year-old Xinzi, who is deaf and quit an annotation crowdsourcing company in May.

With essentially no experience to speak of, she landed the job when she first applied for it. The company, which specifically hired disabled people, drew them in with a monthly salary of 5,000 yuan and the promise of technical training.

“I can’t say it’s a scam because they really do have a lot of disabled people working there,” says Xinzi. “But the salary is definitely not that high. The base salary is 2,000 yuan, plus project commissions … it’s barely enough to get by.”

Her husband was initially very supportive. He had witnessed firsthand her frustration while hunting for a job, so he encouraged her to persevere. He was excited for her to be able to work and live like everybody else — and get paid for hard work.

However, making more money meant more work. “The company talks a good game: they say you work from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. with weekends off,” she says. “But to finish your job, you really end up working overtime every day. If you don’t finish, you can’t make ends meet.”

To save time commuting, and label more images, she later moved into the staff dormitory next to the office building. That left only the weekends for her to go home and see her husband and daughter.

It was the longest time Xinzi had been away from home since her daughter, who had just started elementary school, was born. On video chats, her daughter occasionally asked when she was coming back. “Soon,” was all Xinzi could reply.

When she first started, she did the simpler job of 2D labeling, where she dragged boxes over images to mark planar objects. She spent two to three seconds on each one, adding up to 200 or 300 images a day. “After I got better, I could do 2,000 images a day, which is about the best a skilled annotator can do in a day,” she says.

She had also briefly entertained the idea of sticking it out for a little longer. “It had very little room for advancement, especially for people with disabilities,” says Xinzi.

“Many large companies are researching and investing in semi-automated or automated annotation algorithms, so there’s falling demand for relying only on human labor. The threshold is also very low. As long as you have a computer and you can move your fingers, anyone who keeps at it can become a skilled worker after a while.”

When she got too busy to visit home, she recalls asking herself, “Is this really what I want?” After working there for a year, she watched her colleagues quit one after another. Some could not bear the demanding workload, while some found other positions. In the end, she was the only one left.

After yet another video call with her daughter, she finally decided to quit. Now that she feels relaxed and is able to hold her daughter, she realized that she valued her family’s companionship more than her busy work schedule. The job hunt continues for her online, as she tries to balance between career and family.

Reporter: Long Yang.

Guo Peng, Chen Yufei, and Xinzi are pseudonyms.

A version of this article originally appeared in Code for Life. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Zhi Yu and Apurva.

(Header image: Visual elements from VCG, edited by Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)