Unreal Estate: How Duped Homeowners in Henan Flipped the Script

Before buying his first house, Cao Liang, an IT professional, developed a rigorous algorithm to survey all the buildings for sale in Zhengzhou, capital of the central Henan province. The buildings were sorted according to how much transportation was available nearby, greenery, and other factors.

In the end, he zeroed in on the Yongwei-Jinqiao Xitang complex. It ticked all the boxes. “There was no other competition,” says Cao.

Not only was this complex located in the High-Tech Zone, with two subway lines and roads extending outwards, it was also surrounded by institutions like Zhengzhou University, Henan University of Technology, and Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, among others.

Cao believed its location underscored the “high quality” of its owners. In self-reported statistics in line with the weiquan, or rights protection, movement, 1,172 owners declared themselves as family units, which included 1,313 with bachelor’s degrees, 481 with master’s degrees and 189 with Ph.D.s.

Compared with the average price of 13,000 yuan ($1,900) per square meter in the surrounding communities, the selling price at Xitang reached 16,000 to 20,000 yuan. However, many owners said that they were willing to pay the premium for their dream home.

According to Chinese corporate database Qcc.com, in the Xitang project, the Zhengzhou Jinqiao Real Estate Co., Ltd. holds 51% and Yongwei Real Estate Co., Ltd. holds the rest. While Jinqiao has only been around for five years, Yongwei is an older real estate company, established in 2005, and its reputation is among the best in the city.

Despite all the hype, however, since December 2021, construction on the Xitang complex has been suspended.

At the time, Cao paid little attention to the delay. He believed that work had stopped amid pollution control measures in Zhengzhou. But after Lunar New Year, most buildings in Zhengzhou resumed construction, except for Xitang.

Then things got worse. The first bit of worrying news came after Spring Festival in February, when owners heard that “Yongwei may withdraw from Xitang.” And in April, they discovered that the other shareholder, Jinqiao, had misappropriated around 1.6 billion yuan from the project fund.

As construction stalled, a series of negotiations began between homeowners, builders, and relevant government departments. Believing in the system, and sticklers for the rules, Xitang’s future residents hoped diplomacy would solve the impasse.

But their efforts proved futile. And despite their academic credentials, the homeowners now felt vulnerable. Eventually, Xitang’s owners decided on a new tack: sway public opinion.

Pooling their expertise, owners detailed their experiences into a 70,000-word script, recorded personal video stories of their troubles, and even organized offline public events. Their weekslong campaign, which drew huge support, finally paid off on July 2, when the government announced that the misappropriated funds had been recovered.

Though ultimately successful, the Xitang campaign highlights not only the frustration that construction delays cause homeowners, but also the need for better oversight.

Impasse

On March 11, Xitang owners held the first formal negotiation with the property’s developers.

Hoping to be as well prepared as possible, several owners who were good at putting their case forward verbally and had strong logical thinking volunteered to negotiate for the group, and a representative was nominated for each building unit.

To dot the i’s and cross the t’s, owners made a draft in advance, put forward the requirements of the two shareholders to continue cooperating and deliver quality units. They also hoped the results of the negotiation would be put on paper, which could then be signed and stamped by the three parties.

The negotiations began at around 3 p.m., lasting early into the next morning. In an open letter sent to homeowners, Yongwei Real Estate made it clear that it would not withdraw from Xitang, but Jinqiao responded that though the collaboration to complete the project was on, it was not clear whether it would continue in the future.

Lin Wenchao, an owner, witnessed the entire negotiation process. He says Jinqiao staff made no definite statements about resuming construction, and most of the questions raised by owners were brushed off with: “I don’t know,” “I’m not authorized,” and “I’ll get back to you.”

Cui Hongqi, the man behind Jinqiao Real Estate, should have participated in the negotiations but did not appear at all. The owners waited for him until 1 a.m., eventually leaving in disappointment.

After the first negotiation failed, the administrative committee of the Zhengzhou High-Tech Zone organized two more coordination meetings — on March 14 and March 15.

At these meetings, senior Jinqiao Real Estate representatives made it clear that cooperation with Yongwei would not continue. At the time, some owners thought that this was just because the units “sold too well.” More than half of the 2,500 units had been sold, and there were disagreements between shareholders in the distribution of interests.

In late March, amid further construction delays, homeowners began to petition the local government. After several coordination meetings, the administrative committee of the High-Tech Zone replied by saying: “Procedures have finished, and work has resumed in an orderly manner.”

At the construction site, they saw signs of movement. But then, owners discovered that the project, spread over a construction area of 460,000 square meters, and comprising 16 residential buildings and one commercial supporting building, had fewer than 200 workers on site.

They believed the “resumption of work” was a facade. Several owners said that only in April did they clearly determine the real reason for Xitang’s shutdown. Jinqiao Real Estate had misappropriated funds meant for Xitang and diverted it to develop the Beilonghu project in another Zhengzhou district.

According to meeting records provided by owners, the total funds allocated to the Yongwei Xitang project were 3.99 billion yuan, including 3.37 billion yuan in sales receipts and 612.6 million yuan in loan balances. Cui Hongqi had misappropriated a total of 1.61 billion yuan.

Xitang’s homeowners believed the process would now be simple: hold a meeting to continue negotiations and the work would resume as long as the money was returned. To this end, they continued to organize coordination meetings and also sent formal invitations to the relevant departments of the Zhengzhou High-Tech Zone and officials from Yongwei and Jinqiao.

Lin Wenchao recalls that the message owners hoped to convey to developers and the government was that they were rational people who were willing to talk.

However, from March to May, Cui Hongqi never appeared at a single meeting. Jinqiao’s only representatives were a deputy general manager and the general manager of marketing. Both often only parroted the oft heard, “I am not authorized.”

Lin says that after June, Cui Hongqi attended two meetings organized by district officials but was absent at all the others for reasons including being in “physical discomfort” and having “a yellow health code.”

“We are all educated people here. Such rude communication is very rare,” says Cao Liang, who felt angry, but saw no solutions to their dilemma.

Xitang owners — who ranged from doctors and university professors to financiers and civil servants — always believed rational and proactive communication and cooperation were the tools to solve problems.

But in this dispute over the uncompleted residential complex, such methods proved futile. Lin Wenchao, who also participated in the negotiations, lamented that they wasted months talking, and that he often felt that “all my studies were for nothing.”

Script of life

With negotiations at an impasse, owners knew construction would never resume. Instead, they turned to other options: their standing in society.

Lin Wenchao says he was surprised to learn that over 85% of them had bachelor’s degrees. And as a graduate who majored in communications, he knew his expertise could help find online followers.

Soon, Xitang’s owners posted a video titled “400 Masters and Doctors Want a Home” on WeChat, Weibo, and Douyin. The video was only 40 seconds long, but it was a representation of Xitang’s highly educated owners, such as those who had studied at top domestic universities, those who had Ph.D.s and masters, as well as general managers of enterprises, medical doctors, and IT personnel.

An owner who writes for a living also shared an online document with the group. Everyone was asked to “voluntarily say something about your work, life, and housing.” Lin Wenchao recalls that in two or three days they had a draft comprising around 100,000 words.

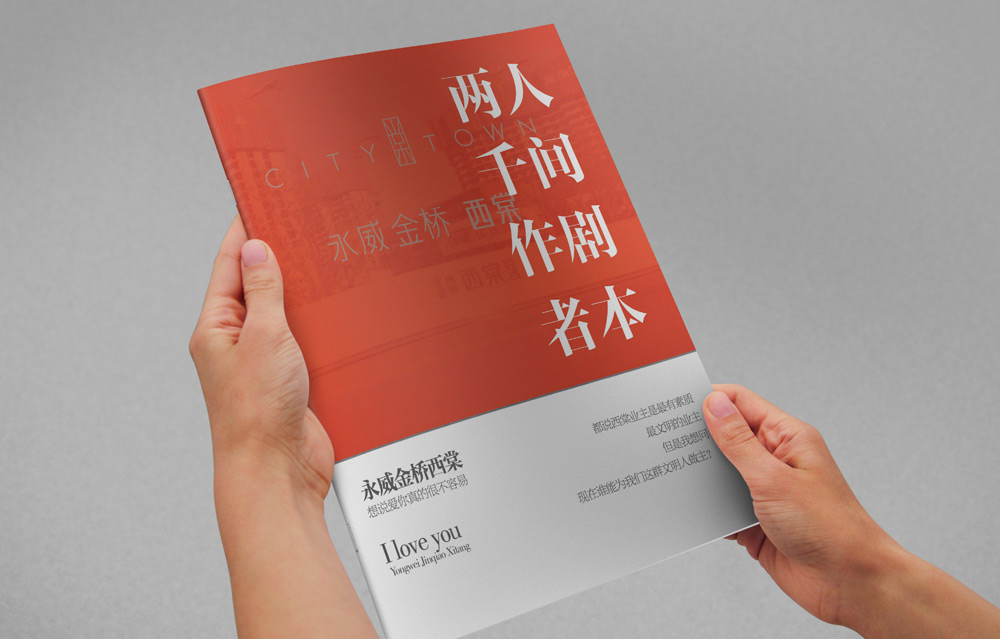

While sorting through it all, they eliminated some of the more impractical and overly emotional writing, and finally completed a draft that totaled 70,000 words. They called it the “Script of Life.”

Simultaneously, some owners also registered video accounts on Weibo and Douyin and began shooting videos based on the real story behind the “Script of Life.” So far, more than a dozen “episodes” of the owners’ personal video stories have been released. As of July 25, they had more than 1.3 million views on Weibo alone.

The campaign reflected what set them apart: most were young and experts in their chosen profession. Gradually, they divided the labor. Those good at editing maintained video accounts; the eloquent communicated with the media; and those with a knack for writing opened accounts on various social media platforms, updated their meeting minutes, sorted through the latest progress, and wrote articles to express their aims.

Chen Li, another owner, is from Henan and went to work in Shanghai after obtaining a master’s degree. Since her elderly parents needed care, she returned to Zhengzhou, investing more than 1.6 million yuan in a house in Xitang.

In the past, she strove to excel in her studies and get promoted at work. Most of the time, she felt that as long as she put in the effort, results followed. But in Xitang, she mostly felt a huge sense of frustration.

“Since no one speaks for me, I’ll write about what I think,” she says. Chen opened an account online to publish articles about protecting one’s rights, and, compared with the “Script of Life,” her articles are more analytical.

While writing about company and enterprise information, she refers to Tianyancha.com, an online database of companies. When she chooses to speak out, she has a red line in mind: she must not write emotionally, but only stick to the facts.

In communications with many owners, Chen clearly feels that everyone thought independently and critically about their current troubles.

For example, at the previous coordination meeting around late May, the High-Tech Zone government proposed a plan to mortgage the unsold houses of Xitang, the value of which totaled more than 1 billion yuan, and obtain a loan of 300 million yuan so the project could resume as soon as possible.

But the owners did not approve. They worried not only about the quality of delivery, but also that this “compromise” may lead to other hidden dangers.

Raw nerve

Owners are also considering whether they should follow the practices of others safeguarding their rights. For example, similarly affected homeowners in some cities choose to live in uncompleted residential complexes.

However, the proposal has not received much of a response. Lin Wenchao says they still hope to safeguard their rights reasonably and legally, with public opinion on their side.

They’ve also been careful in maintaining a “sense of boundary.” Many owners mention in interviews that they must protect their privacy. Their family, careers, and future are all in Zhengzhou, and they don’t want to cause unnecessary trouble.

But “unnecessary trouble” was already in the air. Cao Liang says that in March and April, they held a few offline activities about protecting their rights. Owners familiar with the law reminded people in the group to avoid blocking traffic, comply with epidemic prevention regulations, and maintain safe distances. But there were still some incidents, because “people can’t be rational all the time,” says Cao.

At the end of March, they also organized a “night running group” where they ran in T-shirts with “Let’s Go, Xitang!” printed on them. Some owners traveled across the city to participate in similar activities after work. But after only two runs, they received a call from the police, and the activity was stopped.

As a college teacher, Dong Ye never wanted to be interviewed, worried that it might upset his parents. He and his wife returned to Zhengzhou through a “talent introduction policy.”

Since he holds a Ph.D., Dong enjoys a property purchase subsidy of 100,000 yuan and a living subsidy of 1,500 yuan per month for three years. The total price of the unit they bought was over 2.4 million yuan, with a loan of 1 million yuan.

Most of that was taken care of by Dong’s parents, and the loan set them back 5,600 yuan every month. His father saw the news about Xitang’s problems, but Dong could only comfort him by saying that things would soon work out. But he actually has no idea about when their problems will be resolved.

The volatility of the situation has left Dong anxious. He is engaged in research at school, and his colleagues are very easy to get along with. But on the Xitang campaign, he finds himself inexplicably lost: “The principle of paying money and delivering goods is not tenable here, and there is no integrity to be had at all,” he says.

He also saw news across the country of owners living in uncompleted residential buildings to protect their rights. Living in an incomplete residential building without elevators, water, or electricity, they needed to climb more than 20 floors to their homes, but this was something he did not quite understand at the time.

Later, after experiencing such problems firsthand, he realized: “No one wants to do this, but they’re backed into a corner ... Now I understand that we can all be put in a vulnerable position, regardless of educational backgrounds.”

Perception battle

According to the self-reported statistics of the owners, 246 of them enjoy Zhengzhou’s talent subsidies. The total talent purchase subsidy alone is worth more than 20 million yuan. “Originally, the government used money to lure talent, but now that’s gone,” says Dong.

Dong believes such controversies cause the government huge losses as well. “And it has had a very negative impact, making talents run away,” he says.

According to him, though the government was not responsible for the uncompleted complex, it should have corresponding policies and regulations if it hoped to attract talent in the future. “But not like this, because an uncompleted complex makes everyone lose confidence,” he says.

One owner moved to Zhengzhou after graduating from university in 2009. He first lived in an urban village, eating bowls of noodles for 5 yuan and living in an apartment for 200 yuan a month. At that time, there was no subway, and he needed to ride the bus to work.

This owner said that though it was hard, he felt hope in himself and the others around him. “That kind of hope is like Zhengzhou, which was developing rapidly at the time,” he says, adding that he had the confidence to continue getting by there.

After more than a decade, he had saved enough to buy a house and chose Xitang to provide a better living and educational environment for his family and children.

His is among the 170 stories recorded in the “Script of Life.” For other owners, the uncompleted property is a home they built with their hearts. Some bought it for marriage, and some specifically bought bigger units so many generations could live together.

One exasperated owner has expressed his intention to leave. After staying in Shenzhen following graduation from university, he returned to Zhengzhou to be closer to his family. But recently he has considered returning to a first-tier city, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, or Shenzhen. Such cities may present other challenges but they may also “pay more attention to rules,” he says.

Dong Ye tries to analyze more essential problems, such as the hidden dangers of commercial housing’s presale system. “I will never consider a presale building again, no matter how much hype there is. If the building is not built and the completion rate is not over 90%, I will not consider buying,” he says.

Another owner echoes Dong’s thoughts. “The problem with the top-level design of the presale system is its lack of regulatory measures, which leads owners to bear most of the risks of the unfinished building. Developers, of course, can be indignant, and not fulfill their end,” underscores the owner.

But this long-term thinking, in the end, returns to settling on practical problems. More than three months have passed since negotiations began in March, and the High-Tech Zone government has set up a special team to try and find a solution to the problem.

In a meeting record provided by an owner on June 3, the leader of the Henan Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development said that the matter should have an end date, and the department would pay special attention to this.

Over the past two weeks, Xitang has been among the top internet searches, seen by millions. Lin Wenchao believes that is one driving force, but he is also worried about the possible negative impact of public opinion.

Some netizens have expressed doubts: Why should people who have had a better education receive more attention? For these disputes, Lin felt “very sad,” as this was originally a matter unrelated to education or status. “Every uncompleted residential building should be properly resolved,” he says.

On July 2, homeowners finally received their first bit of good news in months. According to the Zhengzhou High-Tech Zone government, about 1 billion yuan of funds misappropriated by shareholders had been recovered.

The management committee of the High-Tech Zone also announced that it would appoint state-owned companies to supervise the use of project funds to ensure follow-up project construction. The committee assured owners that Xitang strives to be completed and delivered to owners by the end of May 2024.

Lin Wenchao said the announcement brought great relief and that all homeowners are very grateful for the efforts of relevant government departments.

But uncertainties still loom. For example, Jinqiao Real Estate, a major shareholder in the project, has not made a clear statement, and no Jinqiao representatives are attending meetings. Owners worry that there may still be potential issues.

Now, the proposed delivery date is May 31, 2024, which is six months later than the original contract. “Since it took so much effort to get the money back, I hope there will be no more changes,” says Lin Wenchao.

In fact, from the beginning, when they were safeguarding their rights, to the present, owners’ requirements have not changed. They have been clear on one thing: having their homes built, so that they can live in the city in peace of mind.

(At the request of interviewees, all names are pseudonyms except Cui Hongqi.)

Reporter: Liang Ting; intern: Zhou Zihao.

A version of this article originally appeared in Beijing Youth Daily . It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Yang Xiaozhou and Apurva.

(Header image: A father and son dressed in Ultraman costumes pose for a photo in front of the Xitang site in Zhengzhou, Henan province, May 21, 2022. From @社稷师老杨 on Weibo)