Code Red: The Human Cost of China’s Rural Banking Crisis

By the night of June 14, Nie Haiyang was in a state close to emotional and physical collapse.

The 32-year-old was standing outside the headquarters of the Henan Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. He’d been there for four days, refusing to leave despite the police’s repeated threats and his growing exhaustion.

Nie is among thousands of people caught up in one of China’s worst banking scandals in years. In April, four rural banks in central China’s Henan province froze their customers’ accounts without warning. Billions of dollars of deposits were affected — including Nie’s entire life savings.

After weeks of waiting, the depositors still had no idea when — or if — they’d be able to recover their money. Growing increasingly desperate, many had decided to travel to Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province, to appeal to the authorities to intervene. Nie and his family had agreed to join them.

Nie knew the petitioners wouldn’t be welcome in Zhengzhou, but nothing had prepared him for what awaited them. Outside the regulator’s offices, police officers quickly surrounded the small group of depositors. Many others had been detained before they made it to the building.

The officers hadn’t touched Nie and his family, reluctant to use force against his wife, elderly parents, and two children. But they had spent the following days pressuring him to leave, shouting, hurling insults, and issuing threats.

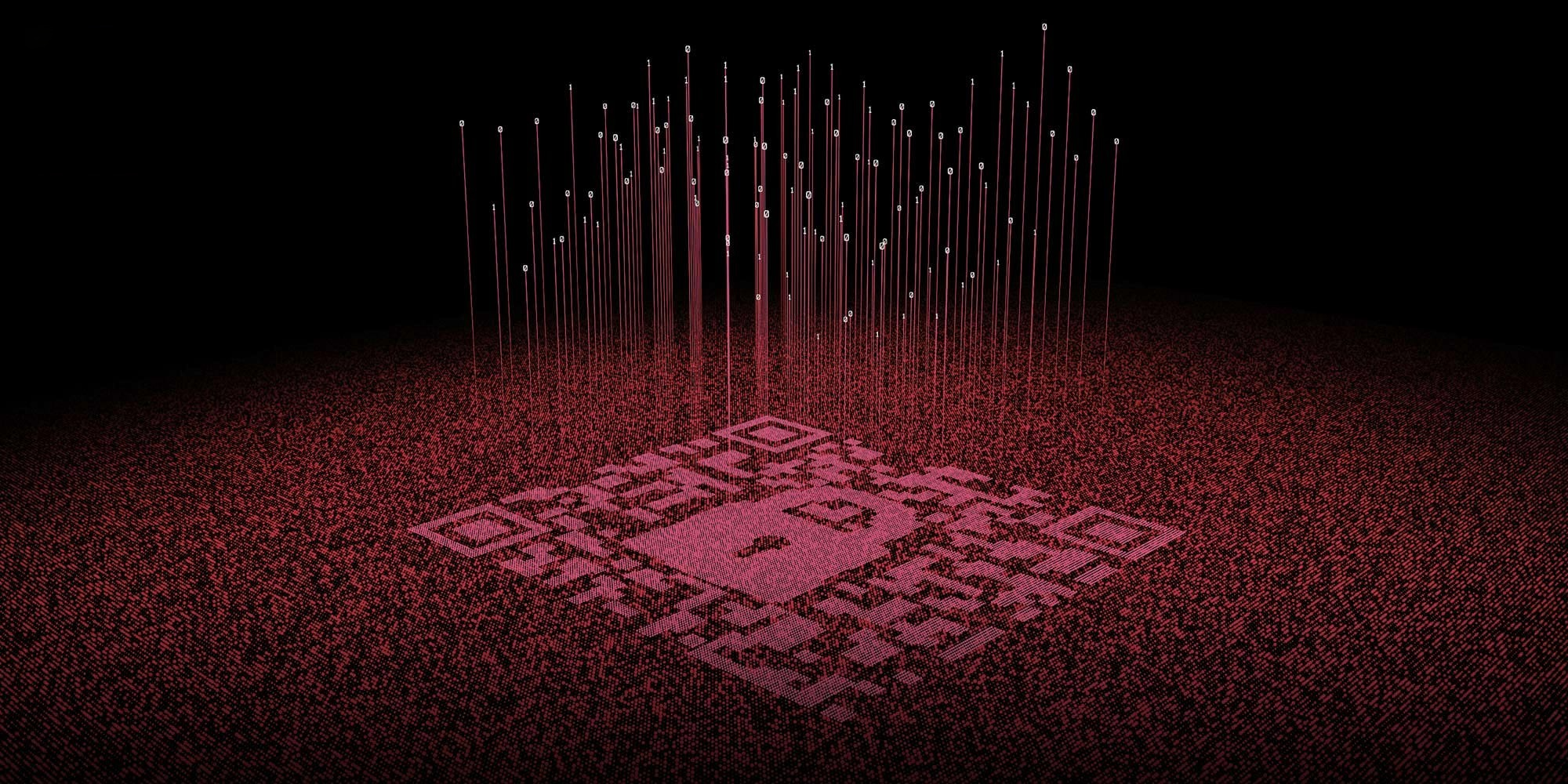

At midnight, the officers finally went home, and Nie’s wife and parents were able to take the children to a nearby hotel to sleep. Nie, however, was unable to join them. As soon as he’d arrived in Zhengzhou, his health code had turned red.

China originally introduced the health code — a color-coded QR code system — during the pandemic to track and trace COVID-19 cases. But the system was now being used to control the depositors’ movements. Anyone with a red code is barred from entering all public buildings, including offices, hotels, and apartment blocks.

Instead, Nie walked down the street to find his relative’s car, where he’d been sleeping for the past four nights. As he stretched out on the back seat, he struggled to calm himself. The stress was wearing him down.

“Maybe this is all I can do this time — I can’t take it anymore,” said Nie, who spoke with Sixth Tone using a pseudonym for privacy reasons. “The police kept saying it’s illegal for me to insist on staying here with a red code, and that I’d go to jail.”

But Nie felt he had no choice but to carry on. If he failed to recover his savings, the consequences for his family would be dire.

His job at a factory in south China pays just 4,000 yuan ($590) a month. Even during normal times, it was barely enough to support his family. But in recent months, his parents have suffered from a stroke and heart problems, respectively. The drugs alone cost over half his monthly salary.

Until April, Nie had been relying on the 200,000 yuan in his savings account to pay the bills. But since losing access to that money, he’d been struggling to keep his head above water. Unless he found a solution within three months, he’d no longer be able to pay for his parents’ health care, he said.

The struggles faced by Nie and other depositors in Henan have shocked China in recent weeks. Many have been unsettled not only by the scale of the banking crisis, but also by the harsh treatment the victims have received.

Four village banks in Henan — as well as a fifth in the eastern Anhui province — began preventing their customers from withdrawing money from their accounts in mid-April. Hundreds of thousands of accounts and tens of billions of yuan were frozen, according to a report by a Beijing-based technology firm that ran the five banks’ online banking systems.

The move came after police in Xuchang, a city in Henan, announced that a shareholder in the five banks was wanted in connection with a “serious financial crime.” The police have since said that a criminal gang had been controlling the five banks and a series of related companies for over a decade, illegally raising funds and then transferring the money elsewhere.

During previous banking crises, China has always taken swift action to protect individual depositors, banking industry insiders told Sixth Tone. But in this case, the banks told the affected customers that their accounts would remain frozen while the authorities continued their investigation. The vast majority have been locked out of their accounts for over three months.

It’s unclear why this decision was taken, but it has had tragic consequences. Sixth Tone has spoken with 30 depositors whose accounts have been frozen in recent weeks. Many of them, like Nie, are ordinary workers who had put most of their families’ savings into the banks.

Several depositors told Sixth Tone they were no longer able to pay their relatives’ medical bills due to their accounts being frozen. In two cases, those relatives had died after losing access to their health care. Multiple sources told Sixth Tone they’d witnessed other depositors attempt to kill themselves.

In desperation, many depositors have traveled to Zhengzhou several times to petition the authorities to intercede on their behalf. Local officials, however, have gone to extraordinary lengths to deter demonstrations.

On several occasions, they weaponized the health code system to try and prevent depositors from entering the city — a scandal that sparked public outrage and an official investigation. Depositors have also been pre-emptively detained by local police and subjected to violence by plainclothes security personnel.

After weeks of mounting public anger, local authorities finally announced on July 10 that customers with less than 50,000 yuan and 100,000 yuan deposited in the banks would be “paid in advance” on July 15 and July 25, respectively. A third batch of payments was announced on July 29 for those with up to 150,000 yuan of deposits.

Yet most of the depositors who spoke with Sixth Tone are still locked out of their accounts and have not received any payments. Many remain anxious that they will lose everything, as the authorities have avoided making guarantees that the money will be returned.

‘Hidden risks’

The crisis has its origins in risky new practices that emerged in China’s rural banking sector during the past decade.

The five banks involved — Yuzhou Xinminsheng Village Bank, Zhecheng Huanghuai Community Bank, Shangcai Huimin County Bank, New Oriental County Bank of Kaifeng, and Anhui Guzhen Xinhuaihe Village Bank — are all village banks, originally set up to provide financing to local communities. But in recent years, many of these rural banks have expanded their reach nationwide.

The five banks — and several other rural lenders — began selling fixed deposit products via major fintech platforms including JD Digits, backed by the Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com, and tech behemoth Baidu’s Du Xiaoman Financial. This enabled them to attract new customers from across China.

Only three of the 30 depositors Sixth Tone spoke with are from Henan province. The others are from 11 different Chinese provinces. Twenty of them opened accounts with the banks via a fintech platform, while the other seven traveled to Henan to open their accounts in person.

To the depositors, the banks looked like an attractive option. China’s “big four” state-owned banks typically offer an annual interest rate of around 3% on a five-year fixed deposit product; the five village banks, however, offered 4.5% on similar products, according to depositor receipts seen by Sixth Tone.

Though above average, the interest rate wasn’t high enough to raise suspicions. Industry insiders considered it reasonable at the time. And the products appeared to be safe investments: all of them were covered by China’s national deposit insurance scheme.

China set up this insurance fund in 2015 to protect depositors in the event of a bank failure. All depositors will receive up to 500,000 yuan if any bank covered by the scheme files for bankruptcy. As of 2021, it covered 4,024 Chinese banks, including all five of the village banks.

Nie opened an account with one of the banks in person after paying a visit to relatives in Kaifeng, a city in Henan, in early 2020. Several had already deposited money in the bank, and recommended it to Nie. Over the following months, he also invested in multiple fixed deposit products via the bank’s app.

“I was attracted by the relatively high interest rate, and I could withdraw the interest I received every month,” said Nie.

By this time, however, Chinese authorities were already growing concerned about the risks posed by rural lenders.

In 2020, there were 89 banks selling fixed deposit products via third-party fintech platforms, of which 84 were small- or medium-sized lenders. Between them, they had attracted around 500 billion yuan of deposits, double the previous year’s total.

In early 2021, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) banned banks from offering long-term fixed deposit products via fintech platforms. It said the trend posed “hidden risks” due to a lack of regulatory capacity.

Meanwhile, policymakers also published a draft regulation prohibiting regional banks from opening accounts for depositors from another province. They added, however, that there would be a “sufficient adjustment period” for smaller banks under severe debt pressure.

After these announcements, JD Digits and Du Xiaoman removed all fixed-term deposit products from their apps. The banks, however, began urging customers to download the banks’ own apps so they could deposit even more money in their accounts, several depositors told Sixth Tone.

Cut off

The first depositor to realize that something was wrong was Xue Jing. The owner of an electrical repairs workshop in eastern China’s Shandong province, she had been a customer of Yuzhou Xinminsheng — one of the five banks — since 2011, when she saw an ad on one of her favorite fintech platforms.

On April 16, Xue wanted to transfer some money from her Xinminsheng account to another account she had with a different bank. The transaction, however, kept failing. She tried calling customer service, but nobody answered. Two days later, the Xinminsheng app went down, with a message stating that the system was being upgraded.

When Xue finally managed to get through to customer services on April 21, the operator told her that she may have been defrauded by criminals via the bank’s online system. They advised Xue to contact the police.

“The same number that they used to tell me to download the app became the one they used to tell me I’d been scammed,” said Xue, who also requested anonymity for privacy reasons.

Nie found out the truth soon after. After finding he was unable to log in to the bank’s online platform, he contacted his relatives in Kaifeng. They told him that local depositors had been having problems making large withdrawals from the bank since March.

When Nie finally got through to customer services in late April, they told him that the bank’s online system was down due to a fraud case, but that its physical outlets were operating normally. He traveled to Henan days later, only to be told he couldn’t withdraw his money as the police were investigating a financial crime.

At first, most of the depositors were concerned, but assumed the matter would be resolved soon. China has seen several high-profile banking scandals in recent years, but the impact on ordinary depositors was contained.

In 2018, a village bank in north China’s Hebei province was found to have issued fraudulent loans worth hundreds of millions of yuan. A year later, Chinese authorities were forced to nationalize the troubled Baoshang Bank — a major lender in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region — before eventually allowing it to go bankrupt.

In both cases, local authorities gave depositors assurances that their money would be protected in accordance with the national deposit insurance scheme, Chen Haohuan, a customer services manager at Luqiao Fumin Village Bank in the eastern Zhejiang province, told Sixth Tone.

“Bank crises caused by insider crimes are not rare in China, but in such events, depositors have always had free access to their savings,” said Chen.

This time, however, the authorities gave no such guarantees. Instead, an eerie silence descended around the case. The depositors’ accounts remained locked for weeks, then months. In May, the CBIRC handed the matter off to regulators in Henan. The Henan authorities didn’t issue any announcements on the case for two months.

Rising panic

By mid-May, depositors were becoming severely anxious. Hashtags related to the Henan banking scandal started trending on Weibo, China’s closest equivalent to Twitter, and Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok.

Many depositors were already struggling financially. Zhou Yun, a depositor from southwest China’s Guizhou province, had to borrow more than 200,000 yuan from friends and relatives to pay for emergency medical treatment for her elderly parents and parents-in-law.

“If it wasn’t for the bank not paying me back, I would have had the money to provide treatment for my family,” said Zhou, who requested anonymity for privacy reasons. “I hate the feeling of begging and borrowing from others … If the bank doesn’t pay me back soon, I don’t know who to borrow from next time.”

As early as April, Zhou had seen other depositors driven to take extreme action. During a visit to a branch of New Oriental County Bank of Kaifeng, she witnessed a woman — who claimed she’d been waiting at the bank for days — threaten to kill herself unless the staff returned her money. The woman then tried to throw herself from a second-floor railing, but was dragged back by several bystanders.

Fearing their money was at risk, depositors organized four large-scale demonstrations in Zhengzhou from late May, gathering on the street outside the Henan banking regulator’s headquarters to petition the authorities. Nie and Xue participated in all four.

The first time, Yang Huajun, the regulator’s deputy director, emerged from the building to speak with the depositors. He told them that their money was guaranteed to be protected, as long as it came from a legal source and hadn’t received “additional interest,” according to video footage recorded by the depositors seen by Sixth Tone.

But things quickly turned ugly. The depositors refused to leave until Yang issued a formal statement reiterating his guarantee. They also demanded access to their savings accounts. Soon after, dozens of security personnel surged into the square and began forcibly dispersing the demonstrators.

The level of force used shocked the depositors. Nie recalled multiple depositors being left with bruises after fighting off the security personnel, who were trying to throw them into a bus. Xue saw officers squeeze a man’s neck and press him to the ground, before bundling him into a car.

“None of us expected that,” said Xue.

When the depositors returned for a second demonstration on June 13, the authorities were prepared. As the depositors entered Zhengzhou, all of their health codes turned red. Those driving to the city were stopped at local toll booths and forced to turn around. Others traveling by train were detained on arrival at Zhengzhou station.

Nie, who had arrived several days early, was one of the very few who managed to get to the regulatory commission building. He brought his family along as protection. “No one dared to come alone. As soon as you arrived, a group of people would press you to the ground and drag you away,” said Nie. “I took the elderly and children with me, so they didn’t dare do anything to me.”

Five officials in Zhengzhou were later punished for interfering with the depositors’ health codes “without authorization,” after the incident was widely reported by the media.

In the wake of this incident, the Henan banking regulator and the Xuchang police — which initiated the investigation into the banks in March — both released updates on the case for the first time in weeks, on June 18. They confirmed that a criminal gang had gained control of the banks’ “online transaction channel” and used it to illegally divert funds. The police said that New Fortune Group, one of the banks’ shareholders, had “committed a series of crimes” since 2011.

But neither announcement mentioned the depositors, whether their money would be protected, or when they might be able to access their accounts. Many depositors told Sixth Tone they despaired after reading the statements.

“It broke my psychological defenses,” said Nie. “I started to think that maybe I wouldn’t get back my money if the police failed to recover the stolen funds.”

Last stand

The depositors reacted by organizing two further gatherings in Zhengzhou, with the final one on July 10 being the largest yet.

On that day, nearly 2,000 people traveled to Zhengzhou from all over China, the depositors estimate. But when Nie and his family arrived at the regulator’s headquarters, they found the building surrounded by a phalanx of plainclothes security personnel, who prevented them from coming within 100 meters of the building.

A few blocks away, a group of several hundred depositors managed to gather on the steps of the Zhengzhou branch of the People’s Bank of China at 5 a.m., where they held up banners and chanted slogans demanding the return of their savings.

For the first few hours, this group was able to demonstrate relatively freely, as local police and a group of men dressed in white watched on. But at 11.30 a.m., the men in white suddenly rushed forward.

Zhou went numb from shock, as she watched the men attack demonstrators as they lay prone on the ground.

“They moved so fast, like a martial arts movie. My brain went blank for a while,” said Zhou. “Three or four men dragged one depositor down by grabbing his hands and feet. His head smashed on the ground, and then hit one step after another.”

Earlier that morning, Zhou also witnessed another depositor attempt to hang himself from a tree in front of the People’s Bank of China branch. Other petitioners cut him down before he perished.

Sowing division

The violence on July 10 triggered further public backlash, after the incident was again reported widely by the media.

A day later, local authorities abruptly released a “risk disposal plan,” which promised to make “advance payments” to two groups of customers who had deposited up to 100,000 yuan in the four Henan banks. The plan was based on the “fund recovery situation,” the notice said.

Once again, however, most of the depositors became even more worried after reading this latest announcement. Throughout the document, the authorities refer to those affected not as depositors, but as “off-book business customers” — a term that was unfamiliar to banking industry insiders who spoke with Sixth Tone.

The unusual language added to existing doubts over whether the depositors’ money would be protected under the deposit insurance scheme. In theory, payments through the scheme can only be made in the event of a bank failing. But the CBIRC has said that the four banks are operating normally, while the local banking regulator said it would formulate a plan for reimbursing the banks’ customers once they had recovered the money from the criminal gang.

It remains unclear when that might happen. By the end of June, around 80 staff members and executives at rural banks in Henan had been detained, Chinese media outlet Caixin reported in early July. Several people inside the banking regulatory system were also under investigation.

Sixth Tone was unable to reach the Henan Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission for comment, as the body’s government assistance hotline had been disconnected. Staff at another department declined to provide an alternative number.

Meanwhile, the “advance payments” have proceeded as scheduled. On July 15, the depositors with less than 50,000 yuan in their accounts received their money. Ten days later, most of those with between 50,000 yuan and 100,000 yuan in the banks also received payments. A number of depositors who are local to Henan province have also been able to recover their money. On the evening of July 29, the Henan Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission announced that a third batch of “advance payments” would be made to people who had deposited between 100,000 yuan and 150,000 yuan in the five village banks.

Yet many others have received nothing. Of the 30 depositors Sixth Tone interviewed, only four have been totally reimbursed, while one person has received a portion of their money back. Two more expect to be partially reimbursed during the third batch of payments. The remaining depositors appear to be losing hope.

Several told Sixth Tone they suspected the payments were designed to reduce the number of people going to Zhengzhou to petition. Nie said he knew around 200 people from Kaifeng who joined the protest on July 10, but as they’re from Henan most of them have now received their money.

“Our energy is even smaller now, and our unity has been broken,” said Nie.

Nie, however, has vowed to continue petitioning. The trips to Zhengzhou are adding to the financial strain he’s under. In the past, he used to travel outside Guangdong just once a year, to save on travel expenses. But he sees no other option.

“If I don’t go, there will be no hope,” he said. “The more people join, the likelier it is that our voices will be heard.”

In China, the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center can be reached for free at 800-810-1117 or 010-8295-1332. In the United States, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached for free at 1-800-273-8255. A more complete list of prevention services by country can be found here.

Update: On the evening of July 29, the Henan Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission announced that a third batch of “advance payments” would be made to people who had deposited between 100,000 yuan and 150,000 yuan in the five village banks. The article text has been updated to reflect this news.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: liulolo/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)