How Climate Change Turned Off the Lights in Southwest China

Sichuan province is known as China’s “power bank.” The southwestern region is one of the country’s biggest electricity producers; the power from its massive hydro dams helps keep the lights on in faraway Shanghai and other Chinese megacities.

Yet Sichuan is now facing its own crippling energy shortage.

The province has experienced the most intense heat wave in decades this month, which has triggered an equally severe drought. Rivers across the province have run dry, leading to a dramatic fall in power output from local hydropower stations.

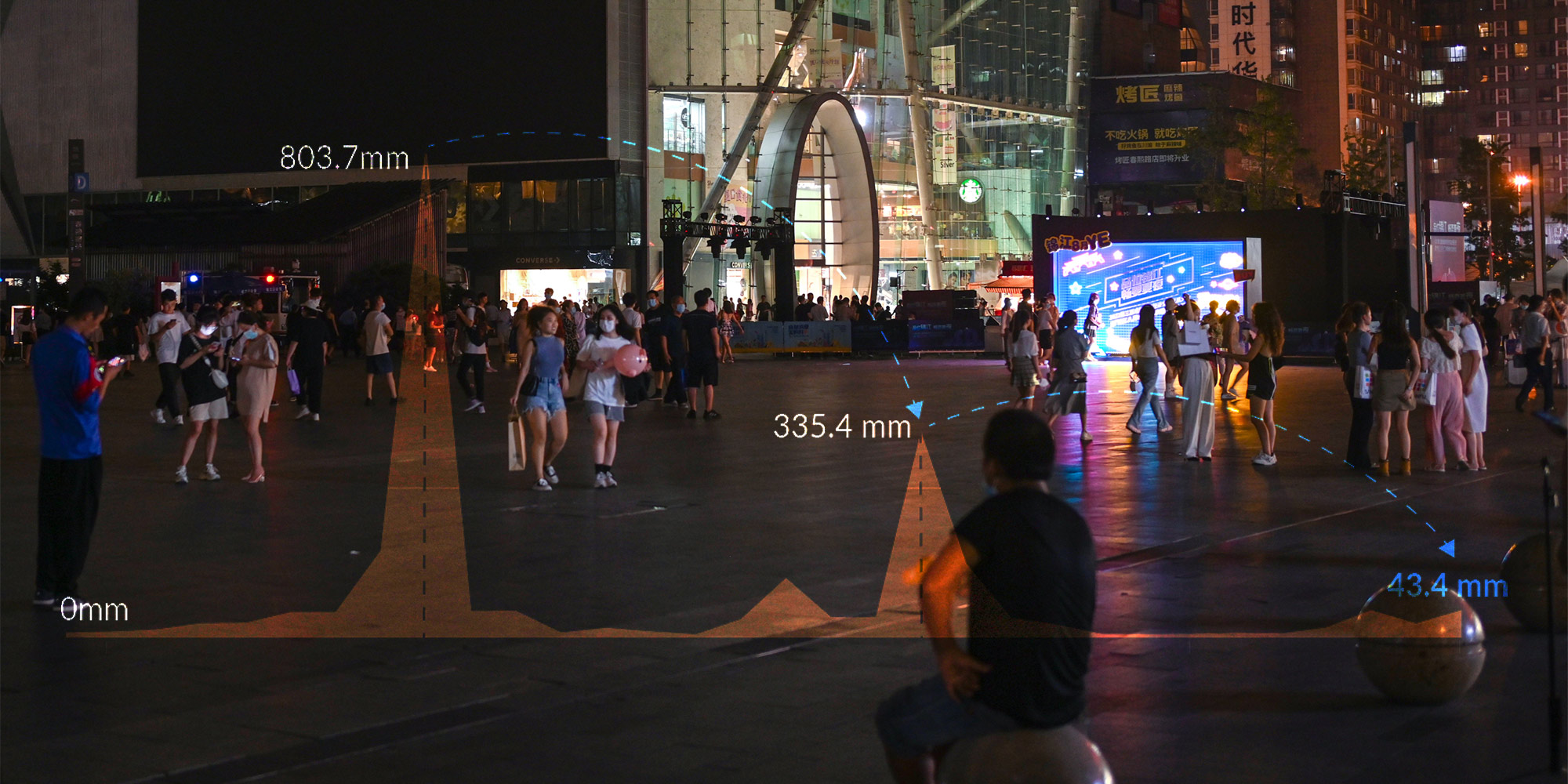

Chengdu, the provincial capital, has been forced to take drastic measures to curtail power use. All energy-intensive industrial plants were shut down on Aug. 15. Subways and shopping malls have gone dark. Air conditioners in public places have been turned down or switched off completely.

In smaller cities, it’s even worse. Dazhou, a city of 5 million in northeast Sichuan, has imposed rolling power cuts since Aug. 16. The local power company says that each neighborhood has to endure power outages of 2-3 hours per day. Local residents claim the cuts are lasting 6-7 hours.

Unable to access air conditioning, people have been gathering on bridges or in underground parking lots to keep cool. Office workers have been bringing giant blocks of ice to their desks. A local resident in Dazhou told Sixth Tone several friends with young children had been staying in a hotel with a backup generator, otherwise their babies would cry all night.

The crisis has shocked China. It’s not only the dramatic scenes of cities going dark, but the way the outages have produced cascading knock-on effects that have rippled across the country’s economy that is causing concern.

The factory closures in Sichuan have sent shockwaves through the supply chain. Tesla, SMIC, and other blue-chip brands have pleaded with local governments to allow their facilities to keep operating. Even cities on the other side of the country are feeling the effects: Shanghai has had to switch off the lights on the iconic Lujiazui skyline to conserve power.

Above all, the heat waves have revealed that China’s energy system is more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than many assumed.

How heat waves scrambled Sichuan’s power grid

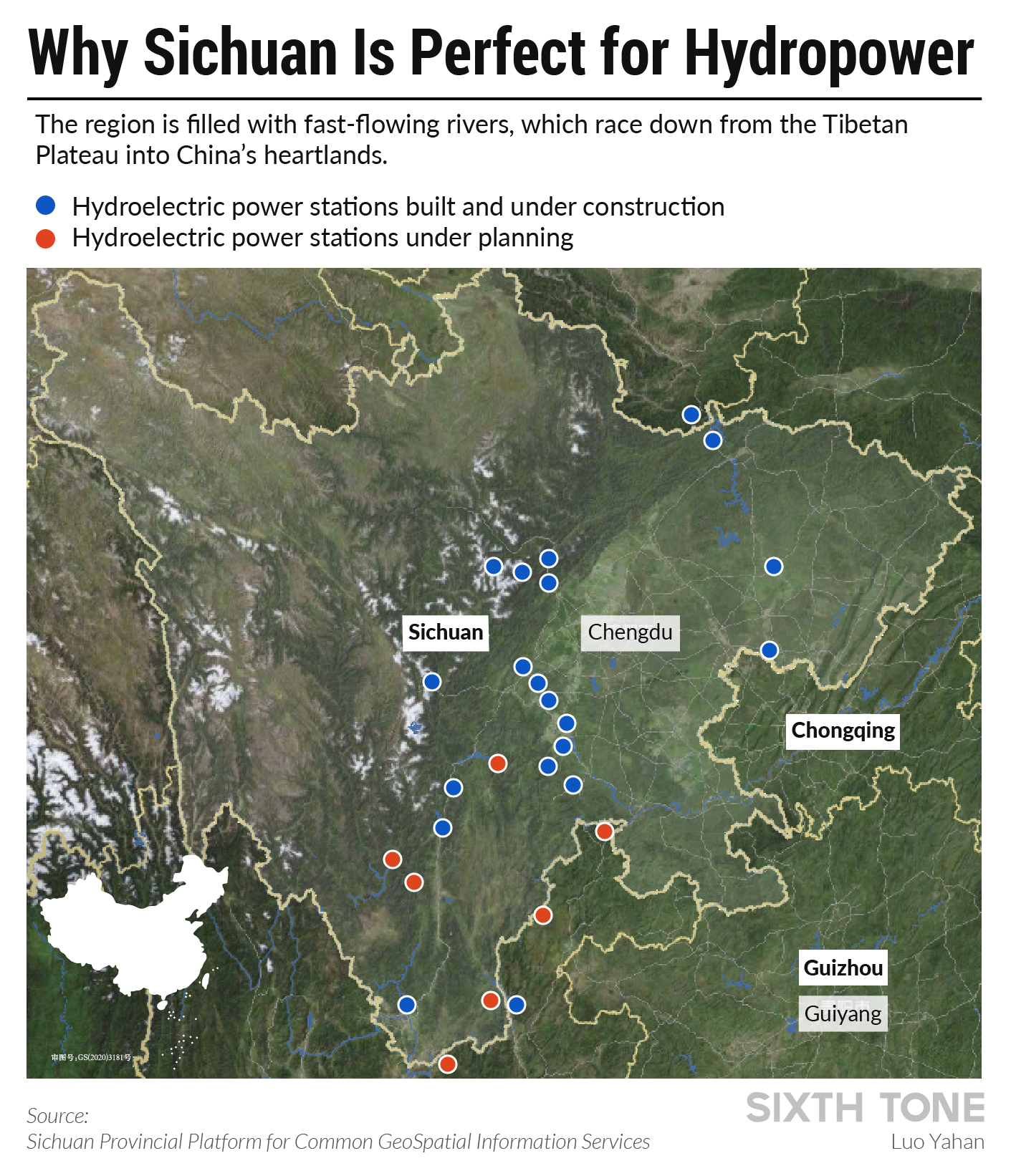

Located on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, Sichuan is perfectly positioned to make use of hydroelectric dams. Many of China’s main rivers, including the Yangtze, rush through the province, falling from an altitude of over 4,000 meters in the west to under 500 meters in the east.

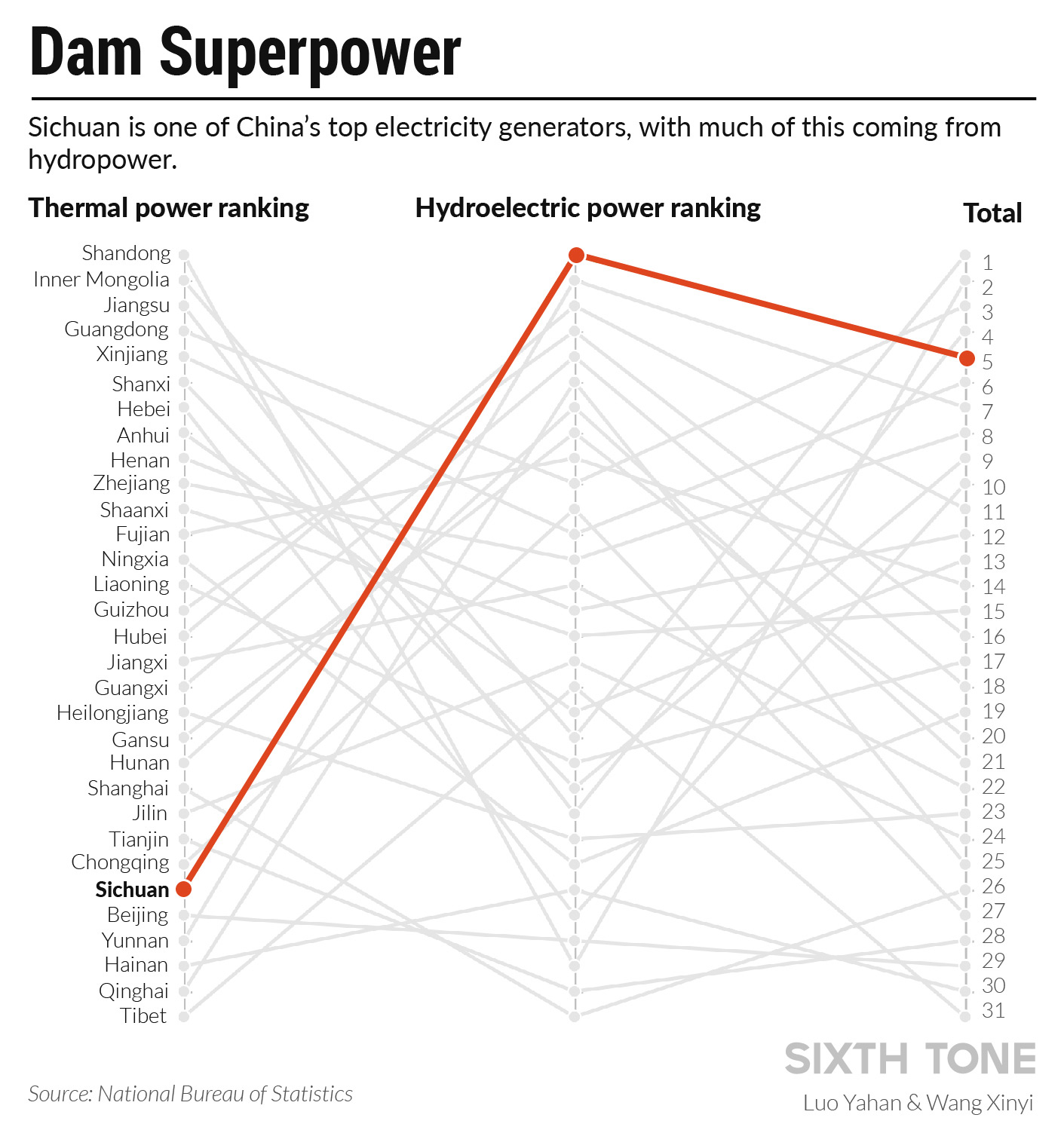

This has allowed Sichuan to become China’s “power bank.” The province generates more electricity than almost any other Chinese region, with the majority of this energy coming from hydropower.

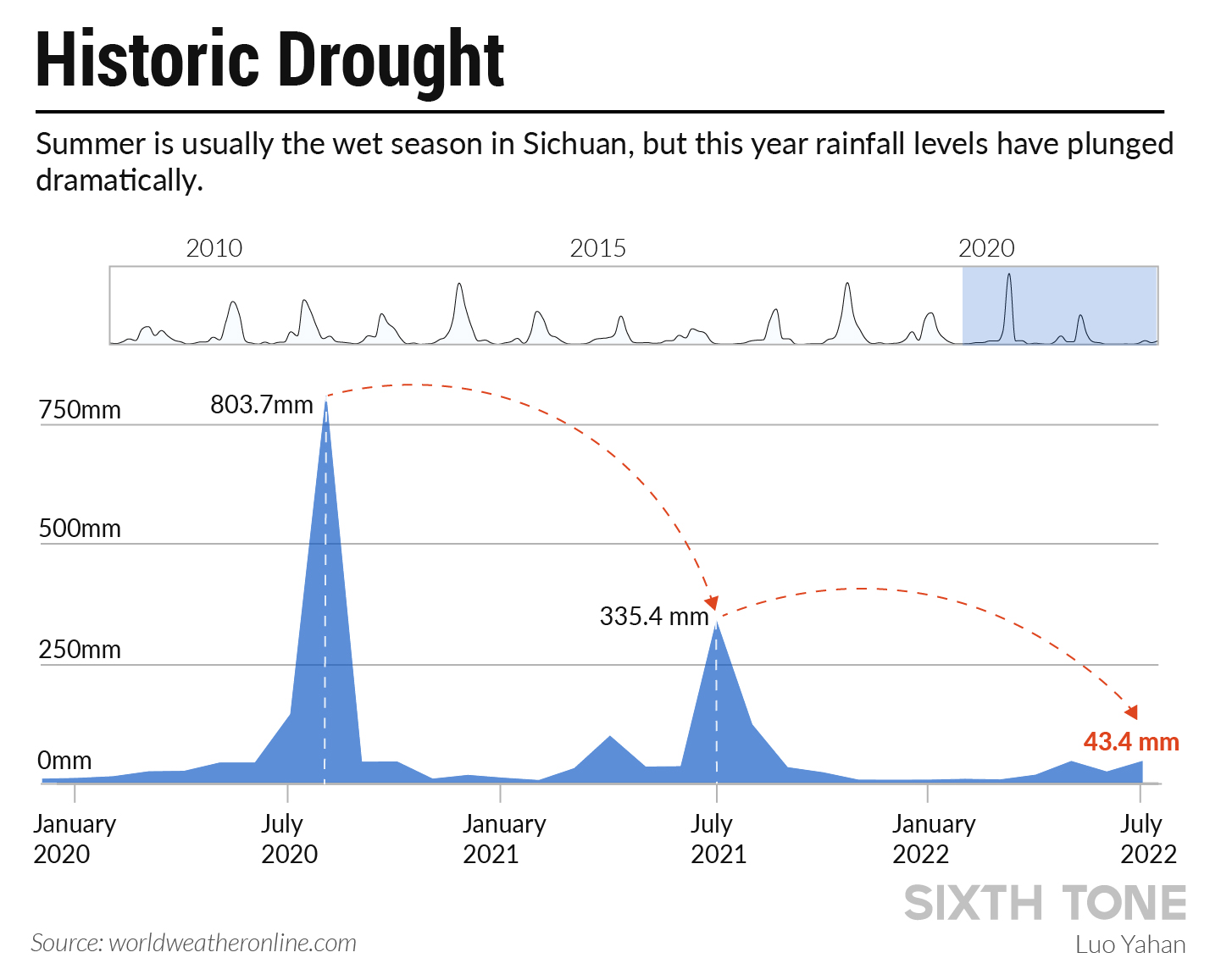

Hydropower, however, fluctuates by season. Summer is normally the peak season, when a surge in rainfall swells Sichuan’s rivers and allows its dams to generate more electricity. During the winter, the province has to rely on coal-fired power stations or purchase electricity from other Chinese provinces.

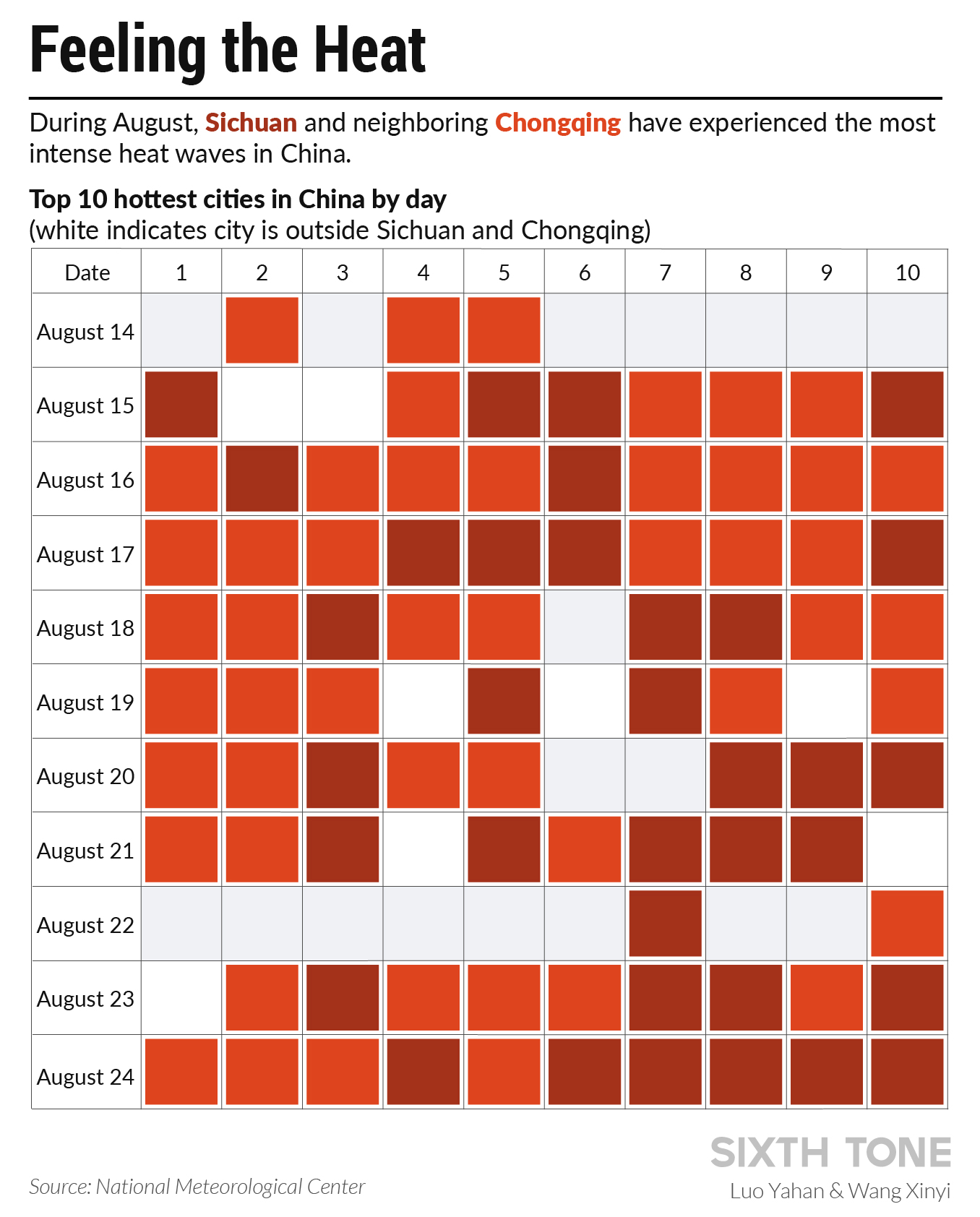

But this year, Sichuan has been hit with intense heat waves and drought. This summer has brought the highest temperatures and the lowest precipitation levels ever recorded in the region, according to the State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company. Sichuan and neighboring Chongqing have experienced the hottest weather of any region in China this month.

Rivers and reservoirs have begun drying up. In Chongqing, a megacity bordering Sichuan, the riverbed of the Jialing River — one of the Yangtze’s main tributaries — is exposed. Water levels at some dams have fallen by nearly 40 meters.

For Sichuan’s power grid, the combination of drought and heat waves is a perfect storm. As water levels plunge, the province’s hydropower generation has also plummeted. Hydro dams in Sichuan are now producing just 440 million kilowatt-hours of power per day, less than half their normal level, according to local media.

Yet electricity demand is surging. Extreme heat means more people running more fans and air conditioners. In Chengdu, air conditioning accounts for 40% of households’ power demand. By Aug. 21, Sichuan’s peak electricity demand had jumped to 65 million kilowatts, up 25% year-over-year.

Sichuan’s hydropower dams cannot cope with the surge. Only one-quarter of the hydro dams in the province are adjustable; the rest are completely dependent on the river flow. No water, no electricity. And even the dams that are adjustable aren’t much help, because the reservoirs have also dried up.

With hydropower generation cut in half, Sichuan’s thermal power plants have begun operating at full capacity. On Aug. 22, 67 thermal power plants in the province produced 12.75 million kilowatts of power, accounting for around 25% of the maximum load on Sichuan’s power grid that day. In the past, thermal power provided less than 10%.

Why the crisis will have far-reaching implications

The power crunch has had a dramatic impact on businesses, with many manufacturers forced to shut down.

As early as July 7, State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company published a notice urging people to reduce their electricity consumption and suggesting companies avoid using power during peak times. A week later, Sichuan had nearly 4,000 industrial firms sign an agreement promising to avoid consuming power during peak times — such as by producing goods only at night.

But that still wasn’t enough. On Aug. 14, Sichuan and Chongqing announced they would put limits on industrial energy consumption to “conserve power for civil use.” Over the following days, local officials extended these measures.

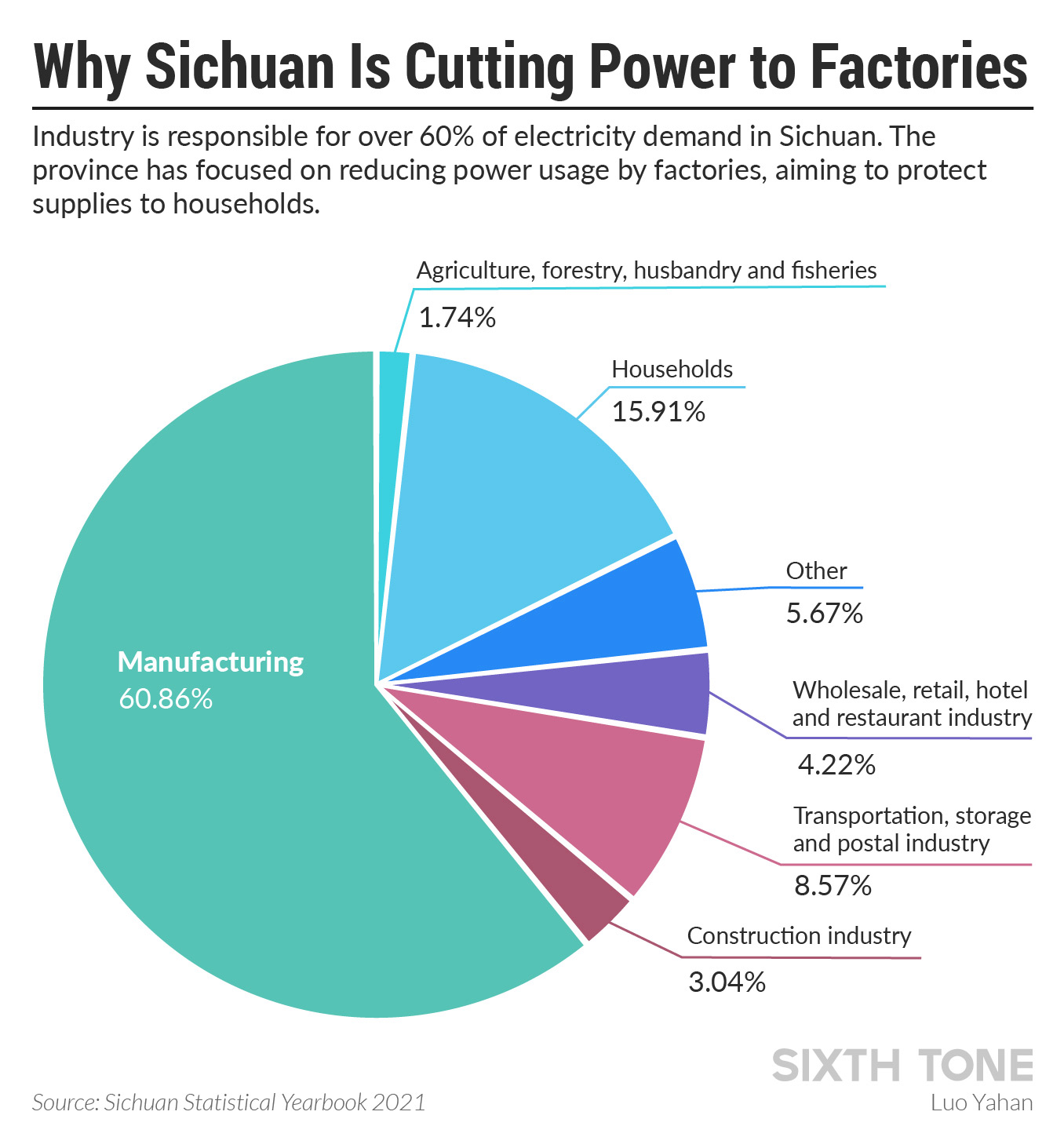

It’s easy to see why industry has borne the brunt of the power saving measures. Manufacturing accounts for over 60% of electricity consumption in Sichuan.

Because of its massive hydropower resources, Sichuan has some of the cheapest energy prices in China. Companies from energy-intensive industries — such as solar panel manufacturers — have flocked to the province as a result. Now, however, they are being kicked off the grid by local authorities.

Other industries being hit particularly hard include auto, aluminum, and semiconductors. Car manufacturers including Tesla and SMIC are trying to lobby the Sichuan and Chongqing authorities to be given priority access to electricity.

The knock-on effects of the drought could last months, with industry insiders predicting Sichuan’s winter power generation will also be affected.

The province’s winter power generation relies heavily on water stored during the summer. During normal years, reservoirs begin storing water from late August. This water is then gradually released to power the hydro dams during the dry season.

But that might not be possible this year. “Now, it seems that the water level is still falling, and there aren’t the right conditions for water storage,” Xu Tao, a local power station employee, told domestic media.

The long-term impact on Sichuan — and China as a whole — could be even more significant. If climate change makes extreme summer heat waves more common, Sichuan’s heavy reliance on hydropower will become a crucial weakness in the country’s energy system.

China’s densely populated eastern provinces currently depend on electricity from Sichuan’s hydro dams. Between 1998 and 2019, Sichuan sent over 1 trillion kWh of hydropower out of the province — enough to power Shanghai’s homes for several years.

The contracts binding these electricity transfers are iron-clad; Sichuan isn’t allowed to stop providing electricity to the east even in the event of an extreme drought. If the province runs out of power, it has to plug the gap using thermal power stations.

But this arrangement may soon become unsustainable. Unless the system is changed, Sichuan is predicted to have a major electricity supply gap by 2025. Burning more thermal power to make up the shortfall is not a long-term solution.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: People shop on a darkened Chunxi Road Pedestrian Street in Chengdu, Sichuan province, where power curtailment measures have been introduced, Aug.18, 2022. Chen Yusheng/VCG)