The Family House

Neighbor Vicki says it’s the first time she’s ever seen fruit on my father’s lime tree. He’d be so pleased, she adds. He died in October 2016, and Vicki has been watching me struggling to clear out the garage, and sometimes offering to assist. The limes are slightly yellow. They’re small, but intensely flavored. We agree it must be all the rain in San Diego this year.

I think of my father often, but the truth is, I don’t miss him. We weren’t close. He was someone who always believed he knew best. Even as a child I knew that wasn’t true, but I’d be lectured, and sometimes beaten for disagreeing. That’s common in Chinese families. Filial piety no matter what.

My mother, who is in assisted living with what’s left of her mind, says she wants to take flowers to my father’s grave.

“There is no grave, Mother,” I reply. “He was cremated and we only have his ashes.” He never specified what funeral arrangements he wanted. Discussions of death are taboo to the Chinese.

My mother wants to get out a bit for some air. Odd. Normally she prefers to look at the outside world from inside.

She limps along behind her walker and asks plaintively if my father will forget her.

I assure her in Mandarin that would be impossible. “He was married to you for 63 years. He couldn’t forget you even if he wanted to.” I don’t mince words. My patience is not abundant, and diplomacy is not my forte. My brother, Bob, is silent. He understands a bit, but he’s forgotten most of his Mandarin and hasn’t done anything to remember more.

My mother smiles a little at my words. I know there were times my parents wished they’d never met at all. He was into poetry and philosophy. She was into small talk and socializing. He was miserly. She was spendthrift. Money flowed through her hands like fast water. My parents fought about that often. But they were together for over six decades.

She misses him tremendously. For some weeks after his death, she demanded that we find a doctor to implant a new pacemaker into his body to resurrect him. Well, no cardiologist is good enough to pull off a stunt like that, and no insurance is good enough to pay for it. Though my mother has stopped asking, she still says I was cruel not to get that pacemaker.

I’ve been sorting through their house, preparing it for sale. It’s not something Bob would ever take on himself. He’s neither capable nor willing. I wake up shivering every morning in the unheated house. It’s a space of about 3,000 square feet, strewn with 40 years of detritus and debris. The furnace is kaput, and the temperature is about 40 degrees Fahrenheit, colder than it is outside. I didn’t pack enough of my own clothes for this trip. I rummage through the closets for something warm, but almost everything is too big — clothes my parents wore when they were in better health, with more flesh on their bones.

Like an archaeologist, I sift slowly through the contents of the house. There are papers, of course — the sort that trail us unceasingly all through life. But the sheer volume is staggering, as if my parents couldn’t bear to part with any scrap of it. Miscellaneous notes, piles of prescriptions and medical reports, tax returns, bills, invoices, ads, boxes of stationery, address books, receipts, ledgers, cancelled checks, uncashed checks, boxes of blank checks from accounts long closed, greeting cards both new and old, notes thanking my mother for generous cash gifts written by people she barely knew, and her long pleading letters to Publishers Clearing House claiming she absolutely deserved to win their sweepstakes. It was the Chinese who invented paper millennia ago, and right now I am not thankful to them. Not one bit.

I come across one box of letters that date back to the 1950s, all written in Chinese. Some are from my father’s family. Blacklisted by Mao’s Red Guards, they did not have enough food, money, or clothes. My grandparents were publicly humiliated, beaten, imprisoned, and brutalized, despite their advanced age. We eventually heard they had died, but not when or how. I don’t read Chinese well enough to understand the content of the old letters. The stories elude me. The details hide from me.

Frustrated, I ask my cousin Tian Ping, who is here on a visit, to translate. She lives in a rural area of Taiwan and her Mandarin is not refined. After reading through a stack of the letters she muses, “They had to be careful what they wrote. The Communists opened their mail.”

I nod, a bit impatiently. That much I know.

“I think our grandparents were selling the clothes our parents were sending them,” she continues. “And they would always list what they received, because there was no guarantee they would get everything that was sent.” Tian Ping and I look at each other grimly. Old photos of my grandparents show them as thin and gaunt, staring at the lens with weary eyes, dressed in the cheap cotton clothes worn by peasants. I touch their images gently and grieve. You were good people. You deserved better.

Tian Ping, her plain round face solemn, tells me, “When your father packed boxes to send them, he would tie the twine so tightly his fingers bled.”

I say nothing. That, I didn’t know. He always said we had to save so he could send his parents money every month, but he never said much about them, never enough to help us know them, make us care about them. And he never knew if the money would reach them. My father was a good man, too. Why didn’t he help us understand?

Tian Ping reads from a letter sent by another relative in the ’60s, during the Cultural Revolution. It had been sent through a friend in Hong Kong. “Please send oil and sugar,” she reads. “We need more vitamins. In the last shipment, there were some things missing. We don’t know who took them. The black market has meat, but we cannot afford to buy any. We are trying to grow vegetables, but sometimes we are too tired to work in the fields. Some neighbors have died of liver disease.”

“They were starving,” I say flatly.

Tian Ping nods. She continues reading: “The price of the wood to make coffins is too high now. Some people just weave grass mats to wrap the bodies in...”

We fall silent. Every letter we open asks for food and money.

Other documents, written in English, reveal details about my parents I never knew, tensions and concerns about money, immigration, employment, and later my mother’s desperate struggles to care for my father, doggedly taking him to specialist after specialist even as her own health declined — something she tried to hide from me, until she couldn’t.

There are also storage boxes of slides and photos in albums, boxes, drawers, letters, sacks. People I know, people I don’t. But their features tell me some are family I have never met. People in America, Hong Kong, Taiwan, the Chinese mainland, Japan. Their babies, children, parents, relatives of all kinds. Weddings, graduations, holidays, visits, vacations.

I unearth my mother’s treasures, one by one. Bolts of silk and velvet, scores of shoes, unopened boxes of Noritake bone china, a gleaming new silver coffee and tea set, ikebana vases, lacquerware, Mikimoto pearls, gold necklaces, bracelets in silver, cloisonne, mother of pearl; rings, brooches, and earrings set in jade, amethyst, diamonds, pearls, coral, turquoise. An even bigger costume jewelry collection — gaudy flower earrings and brooches, rattly charm bracelets. Bed linens, towels, socks. Endless pairs of socks. Why buy one or two white T-shirts instead of a hundred or more? And why not buy a dozen electric pencil sharpeners, and a dozen staplers, too? Two big dressers full of knickknacks and gifts, three closets with unopened boxes of new appliances, unworn clothes from years ago with the price tags still attached, a dozen 60-year-old Chinese dresses custom tailored in postwar Tokyo, and her fake mink stole. There’s a large pile of my father’s stained thermal underwear, left unwashed in the upstairs hallway for months as my mother gradually came undone.

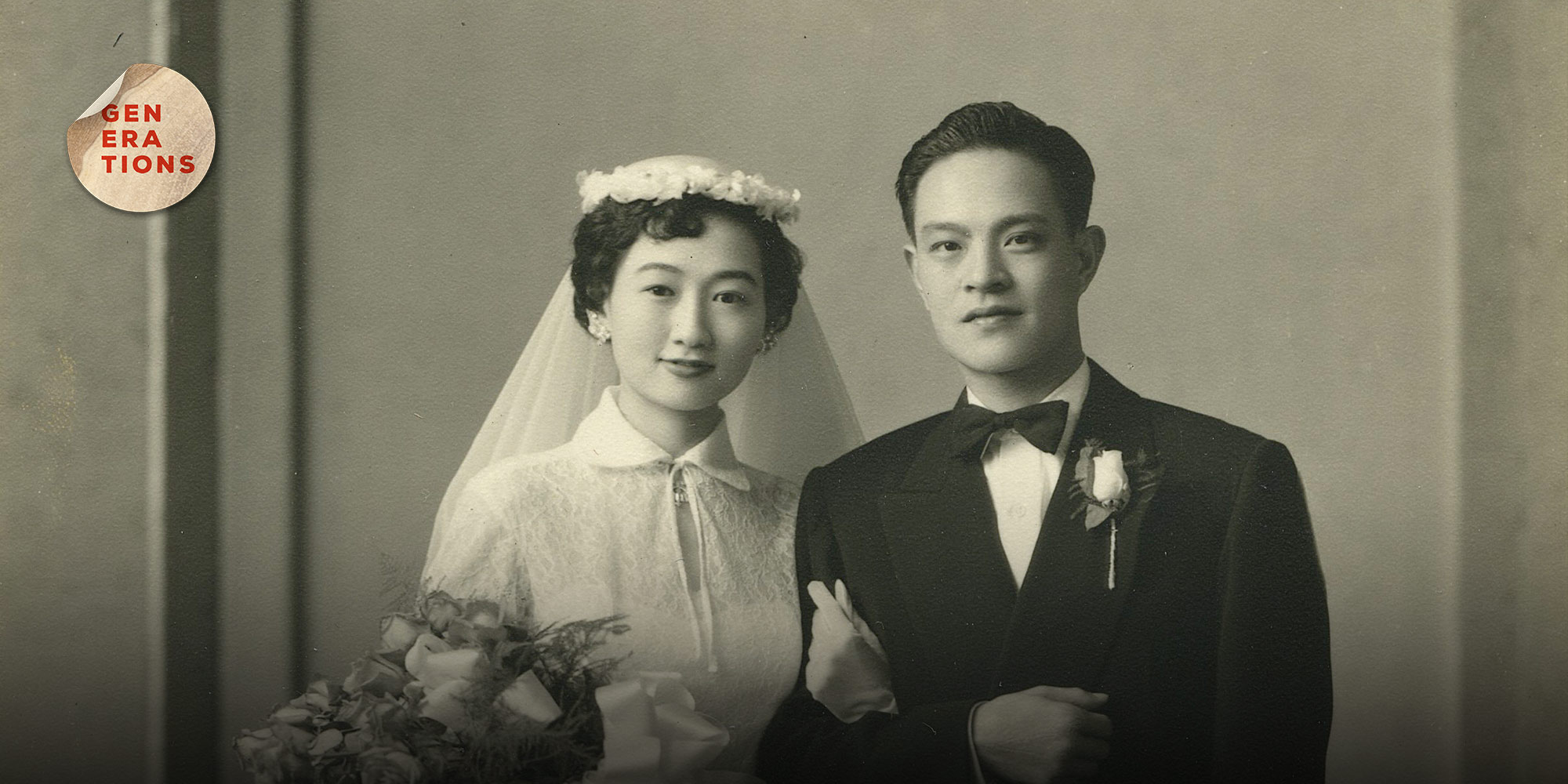

Then I find her wedding dress. That stops me cold, like a blow to my stomach. I last saw the dress about 50 years ago, buried in this same trunk, with that veil and petticoat. The lace is badly yellowed now. The dress has narrow shoulders and a waist that looks about 20 inches. Like all Chinese parents, mine had hoped I would wed and give them grandchildren. That didn’t happen. Their marriage discouraged me from getting married. I became a physician. I stare silently at the dress, sink down to my knees, and start to weep. What am I supposed to do with this dress?

Finally, I make a decision. Drying my tears, I stand and put the old dress on a hanger, arrange it carefully with the veil and petticoat, and take several photos. I’m sorry, Mother. I can’t keep these. This is the best I can do.

And my father? My father was scholarly. He collected books and kept notebooks, stacks and stacks of Time and Newsweek. He laboriously filled out countless flashcards with English words and definitions in his cramped handwriting. But his English never stopped sounding foreign.

There’s much more in the house and garage — much, much more. The reason I haven’t hired someone to sort through and organize it all is because I’m searching for something: my grandfather’s collection of Chinese paintings and his calligraphy scrolls. He served as Chinese consul general in Yokohama, Taipei, and Hong Kong before China turned Red. He was also a well-known calligrapher. For decades I’ve wondered where my mother put his collection. She’s long forgotten, but she’s never let me look for it. She feared I’d make a mess searching the house. As a young girl I once watched a man give my parents a long scroll, unrolling it to reveal a painting of many different flowers. Where is it now? Of everything in the house, my grandfather’s artwork is all I want.

I spend two solid weeks looking through four bedrooms, the kitchen, living room, garage, attic, going through the stuff piled against three sides of the garage. No success. I fill about 20 bins’ worth of trash and recycling. I push, pull, lift, and sort boxes, bags, suitcases, and trunks filled with items ranging from the ludicrous to the sublime. I stand in the garage, exhausted, grimy from the dust. My head and back ache, my fingernails are chipped and filthy, my weight has dropped from 106 pounds to 98. All bad. But the treasure eludes me.

My grandfather’s collection should’ve been in the trunks; that would’ve made sense. They are big and sturdy. But no. My mother used them to pack her dresses and fabric instead. The stronger cardboard boxes contain books, dishes, vases. I finally look at the beat-up flat box tucked into a corner. It is the last box lying unopened in the garage, the one so beat up and ratty it can’t possibly contain anything of value. But when I tear into the decaying cardboard, I find it stuffed it with small watercolors and oils, sketchbooks, and a long box filled with old silk and paper scrolls and flats. The big outer box looks ruined, but the contents are in good shape. Exhausted, my entire body covered in dust, I plop down on a box and laugh. My mother never liked her father. He favored his sons. Maybe putting his stuff in that cheap box was her being passive aggressive.

I bring the long box into the house, carefully unroll the scrolls and unfold the fragile sheets of paper, one by one. On some, my grandfather had written Confucian quotations about morality, but there is also one extolling the virtues of alcohol, rendered in his elegant hand. Wanshi buru jiu. “Nothing is as good as wine.” There are paintings of landscapes, bamboo, pine trees, and a long scroll of carefully detailed flowers. I decide my favorite is an old silk painting of a parrot peering hungrily at some berries on a branch. I name him Lusty.

A Beijing cousin urges me to save everything. I text him a photo of the ratty old box and some of its contents.

“You must save that box,” he replies. His own home is cluttered beyond description, a common phenomenon in China, where high-rise apartments never have enough storage space.

“Ha, I’m not keeping that trash,” I reply. “You want the damned box, you fly over and I’ll give it to you to stick in your apartment.” There is a long silence on the other end.

But later he sends me a message: “After your second uncle died, we found music LPs and foreign magazines hidden in his house. The Red Guards would’ve destroyed them and punished him, you know. I thought he would want us to save his treasures. So we did.”

I think about that, but I don’t think grandfather would consider the dirty cardboard treasure. My mother has always said he enjoyed living it up in Tokyo. Now she’s claiming he was led astray by the Japanese Prime Minister. She’s never said that before. Nobusuke Kishi was a well-known womanizer, drinker, and war criminal. One of the most corrupt Japanese politicians of all time, he was responsible for using Chinese as slave labor in the 1930s and ’40s, instrumental in the military buildup that led to Pearl Harbor.

I remember my grandfather as a tall, thin shell of a man, a very deliberate person with an unreadable face, and someone who had little to say. He would sit quietly by himself and smoke. Perhaps he was different before he lost his position, possessions, and half his family to the Communists. No matter how much his sons revered him, he was no saint. I suspect his conscience bothered him at times, and he took many dark secrets to his grave.

Wearing a cotton gauze mask bought in China by my mother to protect against dust and allergens, I tackle a dusty pile of boxes that had been cluttering up part of the hallway for four decades. I tear open the boxes to find about a dozen Chinese paintings. I gawk at them, completely astonished. My parents and I had walked past those boxes countless times. They’d long forgotten what was in them.

The paintings had been sitting hidden in plain sight for 40 years. There are pieces of broken glass from some of the frames. I’ve since discovered that one painting is likely several hundred years old, and I have been offered a few thousand dollars for some of the others by better known artists. I’m told they will attract Chinese buyers, who like landscapes by famous artists. Seems the nouveau riche tuhao want to buy art and show it off. I’m unimpressed. I sell two of them, the ones I don’t like. But I’m keeping Lusty the parrot. He’s too clever, too whimsical for the tuhao. I take Lusty and the rest of the collection to a rented storage facility.

By dying, my father is bringing about changes in my family that were impossible while he was alive. My parents fought leaving their house for years, even after they both suffered multiple falls. Her last one had my mother screaming and threatening suicide if she was taken away and separated from my father. It put her in hospital with a broken neck and landed my father in a nursing home, apart for the longest time in their married life. Only after that did my mother surrender and agree to move. It’s near impossible to maintain much dignity in old age. Dentures, diapers, dementia, decrepitude, death. The way down is cruel.

My mother’s moods are everywhere and anywhere. I say to her, “May your end be peaceful.” She doesn’t get it. I’ve been away from my own home in New Orleans for almost three months, and I become unkind. “I don’t want to be here anymore,” I say. “You won’t see me for a while. I have to get back to my own life.”

That does the trick. She replies, “Understood.” For a brief moment, her eyes are clear and without tears, her voice perfectly even. She still has some brains left.

“I’m going now,” I say. She begins to cry. She does that often. I walk out and do not look back.

Outside it is raining again. In my parents’ cold, silent house, I sit alone on the old couch and think about my father’s lime tree, my grandfather’s paintings, my mother’s dresses, the photos, letters, books, and papers. My head bowed, I apologize to the old house.

“I’m sorry they neglected you so badly, after you sheltered them for so long,” I say. “It makes me angry to think about it.” I swallow hard and bite my lip. “But now it’s time for you to have owners who will give you the care you deserve.”

This house has many stories. I only know a few; others are lost forever. But in this house sits much of my family’s history — of generations past and long dead — as well as its present. I am surrounded by their photos, letters, and whispers everywhere, in every room. They migrated to many places, many countries. Though I have never known most of my predecessors, we are forever bound by blood, and though I may leave this house forever, I carry their legacy with me everywhere I go. Wherever I am is my home, and theirs.

Author Bio:

Lexa W. Lee lives in New Orleans. She was born in Tokyo to a former Kuomintang officer and the daughter of a Republic of China diplomat. She grew up on Okinawa before emigrating to the U.S. for college. After practicing medicine for over 20 years, she became a medical writer. This memoir is based on the journal she kept after her father died.

“It’s definitely unflattering at times, but that’s real life. It’s not only about the past and its aftermath, but also about picking up the pieces and moving on. No matter where we Chinese have migrated to throughout our history, enough of us hold to our heritage that we continue to survive as a people.”

(Header image: A wedding photo showing the author’s parents. Courtesy of Lexa W. Lee)