On China’s Job Platforms, a Furious Struggle Over Sexual Harassment

When Fangzi decided to look for an internship earlier this year, the 20-something turned to the same resource as millions of other young Chinese: the job platform Boss Zhipin.

After a quick search on the app, Fangzi found a position as an assistant to a company’s sales manager. At first, everything seemed to go smoothly. She was invited for an interview the same afternoon, and started work the following day.

But Fangzi soon began to feel uneasy. During the interview, the manager had asked her if she was single. When she’d questioned why that was relevant, he’d backed off. Yet once Fangzi started the internship, he began pushing again. After work, he sent Fangzi a flurry of suggestive texts.

“He said I should be more enthusiastic and hug him when I’m in the office,” recalls Fangzi, who spoke with Sixth Tone using a pseudonym to protect her privacy. “He even asked me if I was a virgin, and about my sexual preferences.”

Over the following days, things escalated further. At a company dinner, the manager plied Fangzi with alcohol, then tried to insist on taking her home. Fangzi refused. The next morning, he threatened to stop training her unless she agreed to sleep with him. He also said he was deducting her salary due to her “unacceptable behavior.”

Fangzi quit the job that afternoon, and later shared her harrowing experience on the social app WeChat. In the process, she joined a growing movement in China. All over the country, women are speaking up online to name and shame predatory bosses — and pressure leading job sites to kick them off their platforms.

A deep-seated problem

Chinese job platforms like Boss Zhipin, which has over 200 million registered users, have become unwitting conduits for this abuse. Thousands of companies use the sites in a range of predatory ways: sexually harassing female users, hiring young women for corporate roles where they’re expected to sleep with managers and clients, and posting fake modeling and dancing jobs that later turn out to involve sex work.

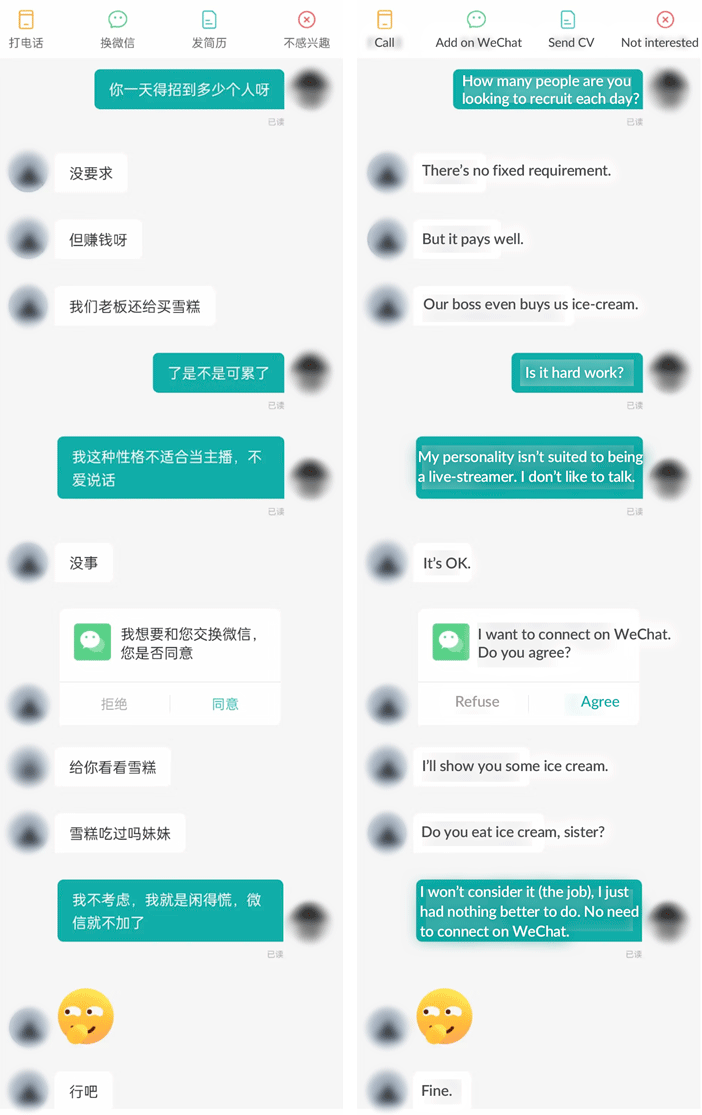

In many cases, recruiters use euphemisms to let female candidates know the nature of the job they’re hiring for. Ling Dang, a Boss Zhipin user from east China’s Fujian province, told Sixth Tone that she received repeated messages from one recruiter on the platform, who kept asking her: “Do you eat ice cream?”

It was only when Ling searched for the phrase online that she realized “eat ice cream” has a range of sexual connotations, from performing oral sex to sending pornographic photos.

Recruiters may also hint at a role’s sexual nature by stating that candidates are required to wear black fishnet stockings, Tong says. Other common red flags include managers asking female candidates if they are “extroverted,” or telling them they’re willing to personally train and develop them.

In other cases, women are hired for regular-looking positions through job platforms, and only find out later that the roles are sexual in nature.

“I’ve had a lot of women talk to me about job posts for models and dancers on recruitment platforms,” Tong says. “These advertisements look like they’re searching for models. However, it’s only after the interview that women discover they have applied for a type of sex work.”

Tong is referring to huachang, a type of nightclub featuring female dancers. In reality, however, the clubs are akin to brothels: Clubgoers can pay for the dancers to drink and chat with them, and there’s often an expectation that they’ll accompany them to their hotels at the end of the night, too.

“In the beginning, these women will undergo dancing and catwalk training, so they do look like modeling or dancing jobs,” says Tong. “However, once they start working in the clubs, they get pressured by the people running them to perform sex for money with the clients.”

Xiao Yu, another Boss Zhipin user, was approached by a recruiter in Changsha, the capital of central China’s Hunan province, who was looking for women to work in this kind of club.

“The job ad was very simple, and the recruiter gave no indication they were looking for anything promiscuous,” says Xiao. “But when he added me on WeChat, he said I could find a rich boyfriend there.”

According to Xiao, the recruiter pressured her to come to the bar to “earn some money.” Although he didn’t say what she’d have to do, Xiao thought it sounded dangerous, and refused to go.

After she posted about her experience on the Twitter-like social platform Weibo, other users who had been approached by the same recruiter confirmed that the club was a huachang.

Pushing back

China’s women have few tools to protect themselves in these situations. Reporting incidents via companies’ internal channels or the Chinese legal system often leads nowhere.

China introduced its first law banning sexual harassment in 2005, and added a new article to its Civil Code compelling employers to take action to prevent workplace harassment in 2020.

In recent years, there has been a string of high-profile cases in which women have reported incidents of sexual abuse and failed to find the justice they were seeking. In August, Zhou Xiaoxuan — also known as Xianzi — lost her landmark sexual harassment case against the famous TV host Zhu Jun, with the court citing a “lack of evidence.”

Last year, an employee at the Chinese tech giant Alibaba accused her boss of sexually assaulting her during a business trip. The manager was dismissed, after being detained by police for “forced indecency.” Yet, months later, Alibaba also fired the accuser, stating that she had “spread false information” and “damaged the company’s reputation.”

Instead, many Chinese women are resorting to reporting incidents directly via social media. Even if they’re unable to obtain justice for themselves, they can at least call out abusers, warn other women about predatory companies, and pressure platforms like Boss Zhipin to take action.

The campaign to get harassers and toxic workplaces kicked off job platforms is a scattered, grassroots movement — the strict supervision of Chinese social platforms makes a formal campaign almost impossible.

Many online feminist groups have been shut down in recent months. Posts with explicitly feminist content are often removed for inciting “gender opposition.” And hashtags that include terms deemed inappropriate or sensitive — including the words “sexual harassment” — are liable to be deleted, several Weibo users told Sixth Tone.

So, individuals are posting about incidents under a range of inoffensive-sounding hashtags, such as “strange job post” and “weird HR.” They’re also reporting abusers to Boss Zhipin directly, and asking the platform to delete their accounts.

The campaign appears to be making a real impact. In August, a Weibo user claimed that a recruiter in Guangzhou was using Boss Zhipin to hire young women to work as sex workers. The post went viral on Weibo, receiving over 10 million views and thrusting Boss into the national spotlight.

A few weeks later, Boss Zhipin announced it had blacklisted over 200,000 recruiters it accused of “sexual harassment, publishing pornographic words or pictures, or other sexual harassment behavior,” banning them from the platform.

The platform also seems to be taking users’ individual complaints seriously. Ling reported the recruiter who asked her about eating ice cream to Boss, and the company blocked his account immediately. Xiao also succeeded in getting the huachang nightclub recruiter blacklisted.

For Tong, social media has become an effective tool for pressuring companies to protect their female users. “The public discussion itself can … promote the resolution of the incident,” she says. “In the internet age, anyone’s voice can be heard and amplified.”

But there are also limits to what the campaign can achieve. Another Boss Zhipin user told Sixth Tone she had reported a recruiter to Boss Zhipin, as he’d posted an ad stating that candidates were required to wear fishnet stockings. The platform deleted the ad. Soon after, however, the recruiter reposted the ad, but changed the wording to say that the employer provided a uniform. This time, the post was not deleted.

It’s also hard to regulate huachang posing as modeling agencies, according to Tong. Chinese law doesn’t prevent employers from advertising for women who look a specific way, and the businesses are usually careful not to leave digital evidence of what they’re really doing.

And ultimately, it shouldn’t be the victim’s responsibility to enforce change, Tong says. Real progress will only come when the whole of Chinese society begins to take women’s safety more seriously.

“To solve the fundamental problem, we need to change the environment itself,” says Tong. “The solution lies within the problem, not the victim. There need to be systems and education around sexual harassment in place.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Woocat/VCG)