Why China’s Environmental Impact Assessors Are Giving Up

Whenever an environmental impact assessment (EIA) professional takes on a new job — regardless of whether it’s something big, like a dam or major land reclamation project, or smaller, like a plastic factory — we already know what the final outcome will be: approval.

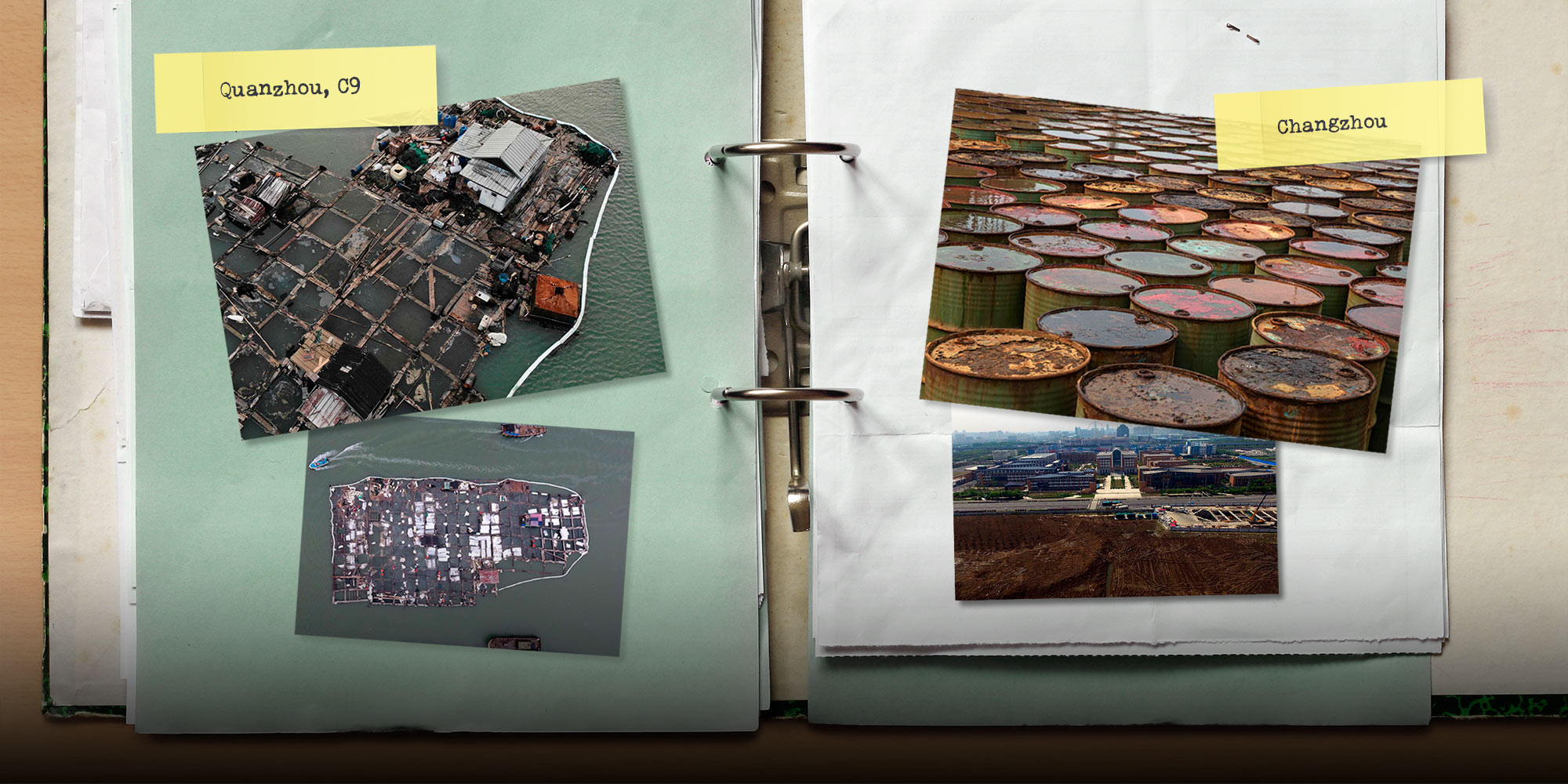

This is true regardless of the reality on the ground. In 2016, hundreds of students at an school in the eastern province of Jiangsu fell ill. Later, parents learned that the school, built in 2010, was located about 200 meters from a former chemical plant. Not only had construction started prior to the completion of the necessary EIA report, but the report, which found evidence of pollutants, was approved despite skirting the subject of the potential health hazards posed by this contamination.

In theory, any construction project in China involving environmentally sensitive areas, pollution risks, or other, similar hazards must submit a completed EIA and receive government approval before construction can begin. The reality is different. Approval is oftentimes a formality, and assessors like myself a pawn in a game played by multiple powerful stakeholders.

None of this was clear to me more than a decade ago when I chose to major in environmental engineering. I figured that, after decades of rapid agricultural and industrial development, environmental protection and reclamation would be important to China’s future. Few of the people around me seemed to share my conviction. I even had relatives joke that I was majoring in street cleaning.

Yet, over the past decade or so, as public awareness of environmental issues rose, the environmental protection industry grew rapidly. The year after I graduated, 2014, saw the release of China’s revised Environmental Protection Law. The amended law, which took effect in 2015, clarified the importance of sustainable development and environmental protection and outlined new protection measures and punishments for violators, such as ecological red lines.

Some of these measures, such as those aimed at reducing emissions, have made important strides, but efforts both before and after the Environmental Protection Law to reform the EIA assessment process have had more mixed results.

This was driven home, at least for me, by the 2018 carbon nine (C9) spill in Quanzhou, along the coast of the southeastern province of Fujian. A leak at a petrochemical terminal in Quanzhou Port ended up releasing 69.1 tons of C9 into the ocean, polluting the water and sickening dozens of nearby residents. In the aftermath, the public began asking questions about the terminal’s construction process, which took place without prior EIA approval. Had the EIA report been conducted in accordance with regulations, then the leak’s damage might have been limited.

That’s just one example of the scandals that have cast doubt on the integrity of EIA reports and the people who draft and approve them. But the truth is, we’re putting too much faith in EIA assessors to navigate a system that all but sets them up to fail. Most EIA assessors are hired by the construction agency, and the two sides typically share the same goal: getting the report approved smoothly, regardless of its findings. After all, that’s the only way they get paid.

In places like the United States and Hong Kong, public scrutiny helps keep EIA assessors and government regulators honest. Although the Chinese mainland has made progress in recent years when it comes to public participation in the construction approval process, including by requiring full disclosure of EIAs, problems remain. For example, EIA reports in Hong Kong generally have a monthlong public disclosure period, compared to between five and 15 business days on the mainland. That doesn’t allow for sufficient checks and balances on the construction process, nor does it encourage construction companies — or even EIA agencies themselves — to take the investigation seriously.

This attitude is reinforced by the fact that EIAs are typically performed only late in the planning process, after firms have already invested capital in land and staffing. Firms also pay for EIAs in installments, with the final payment due only when — or if — they are approved. EIA agencies, unwilling to bear the loss of a client, often pressure assessors to negotiate with the construction firm. This forces the assessor to juggle two contradictory responsibilities: ensuring there are no major errors in the final report and paving the way for approval by “optimizing” minor issues away.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Over the past 10 years, the Chinese government undertook a series of reforms to reduce red tape, prevent rent-seeking behavior by agencies with government backgrounds, and introduce market competition into the EIA process. Previously, EIAs were undertaken directly by local governments, which frequently had a stake in the speedy approval of new development projects. Even after EIA agencies were ostensibly split from the government, many agencies had close ties to regulators, leading to widespread rent-seeking and conflicts of interest.

To address the issue, China began doing away with many of the bureaucratic hurdles for entering the EIA sector. Within a few years, official approval was no longer needed to start an EIA agency. At least one qualified, registered assessor was still required to carry out EIAs, but agencies themselves no longer needed government sanction to operate, drastically lowering the threshold to entering the industry.

These reforms, the most recent of which took effect in 2018, were divisive among assessors. They lowered the costs of the EIA process for smaller projects — an EIA form that used to cost between 20,000 and 30,000 yuan ($2,800 to $4,200) to produce now costs only 10,000 yuan — and the number of EIA agencies has grown eightfold since 2018. But many assessors, myself included, believe that it has made our lives harder by forcing us to compete with lower-quality agencies.

Under the new rules, an EIA report has to be compiled by a licensed assessor, but they can be assisted by other staff, as long as they are full-time employees of the agency conducting the assessment. This has led to a free-for-all, as assessors have begun collecting fees by signing off on reports produced by others. In one reported case, an EIA agency with a single registered assessor on staff somehow managed to produce 64 EIA reports and 1,576 EIA forms across 25 province-level regions in just four months’ time.

To keep up with demand, assessment agencies rely on templates, updating only a handful of things from one report to the next. These templates shorten the writing process, but they are incompatible with the spirit of the EIA system.

For their part, construction project managers naturally prioritize speed when selecting an EIA agency. An additional month spent in the writing and approval processes means an additional month of costs, so they prefer an agency that can work fast or one that has a good relationship with local regulators. The EIA process, from writing to approval, generally takes between four and nine months, but certain EIA agencies, relying on templates and a staff of unqualified writers, promise shorter turnarounds, sometimes as fast as two months.

This all adds up to a deluge of fake, inaccurate, or plagiarized EIAs. In July, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment blacklisted 265 EIA companies and 217 assessors after a nationwide screening process.

By late 2019, in an effort to keep up with an increasingly fast-paced, cutthroat industry, I was working 12 hours a day, six days a week. It was an untenable situation that eventually pushed me out of EIA business and led me to take a job with an environmental protection organization. Conditions have not improved in the years since I left: Thanks to the pandemic, local governments are under mounting pressure to maintain economic growth rates, which has led many to grant EIA exemptions to firms they believe pose lower risks of pollution. As business dries up, many of my former colleagues have likewise left the industry.

I continue to believe that environmental impact assessments are a vital tool for understanding and identifying potential environmental hazards before they become problems. But with EIA work still regarded as a mere formality, and the people who perform it seen as interchangeable pawns, the system is in dire need of a ground-up overhaul.

As told to Sixth Tone’s Cai Yiwen.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editor: Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Photos from the C9 leak in Quanzhou (left) and a school pollution case in Changzhou, Jiangsu province. Visuals from IC, Zhou Pinglang, and VCG)