In China, Millions of Women Never Learned to Read. Can TikTok Help?

At first glance, Liu Bingxia’s lesson looks like any regular Chinese class: The 47-year-old stands in front of a blackboard, reading out the characters she has neatly written in white chalk. “Siji — driver,” she says, then calls on students to repeat the word back to her.

But Liu is no ordinary teacher. Each of her online lessons is attended by thousands of people from all over China. They are overwhelmingly female, mostly working-class, and often from ethnic minority groups. And they are desperate to learn.

They watch Liu’s classes while sitting in construction sites, on the sides of highways, and in the fields. Many squeeze in lessons during work breaks, or while their children are sleeping. They often view her content not only as a way to learn, but also as an opportunity to transform their lives.

Liu is part of a growing grassroots movement that is using social media to tackle an often overlooked problem in China: the stubbornly high illiteracy rates in some parts of the country.

Though China has made huge strides in improving access to education over recent decades, around 2.7% of the population is still unable to read, down from 4.1% in 2010. That’s more than 37 million people.

In effect, they’re the people that fell through the cracks of the Chinese system. During previous decades, rural families often couldn’t afford to send all of their children to school. In many cases, the sons received an education; the daughters did not.

This inequality has left a sobering legacy: Today, three-quarters of illiterate people in China are women. A disproportionate number are also disabled, from minority backgrounds, and live in remote, mountainous areas, Wang Li, a professor of adult education at Beijing Normal University, tells Sixth Tone.

For the millions of women affected, their denial of an education has had lifelong consequences. They are shut out of almost all white-collar professions. Basic daily tasks — from buying a train ticket, to operating a smartphone — are hugely challenging. They are often totally dependent on their families and partners, which leaves them vulnerable to mistreatment and abuse.

In China’s cities, adult education centers offer marginalized groups a chance to learn to read in later life. These facilities, however, rarely exist in the countryside. Overstretched local authorities have focused their resources on ensuring all children receive a primary education — a target that the vast majority have now achieved — but illiterate people from previous generations have been left behind.

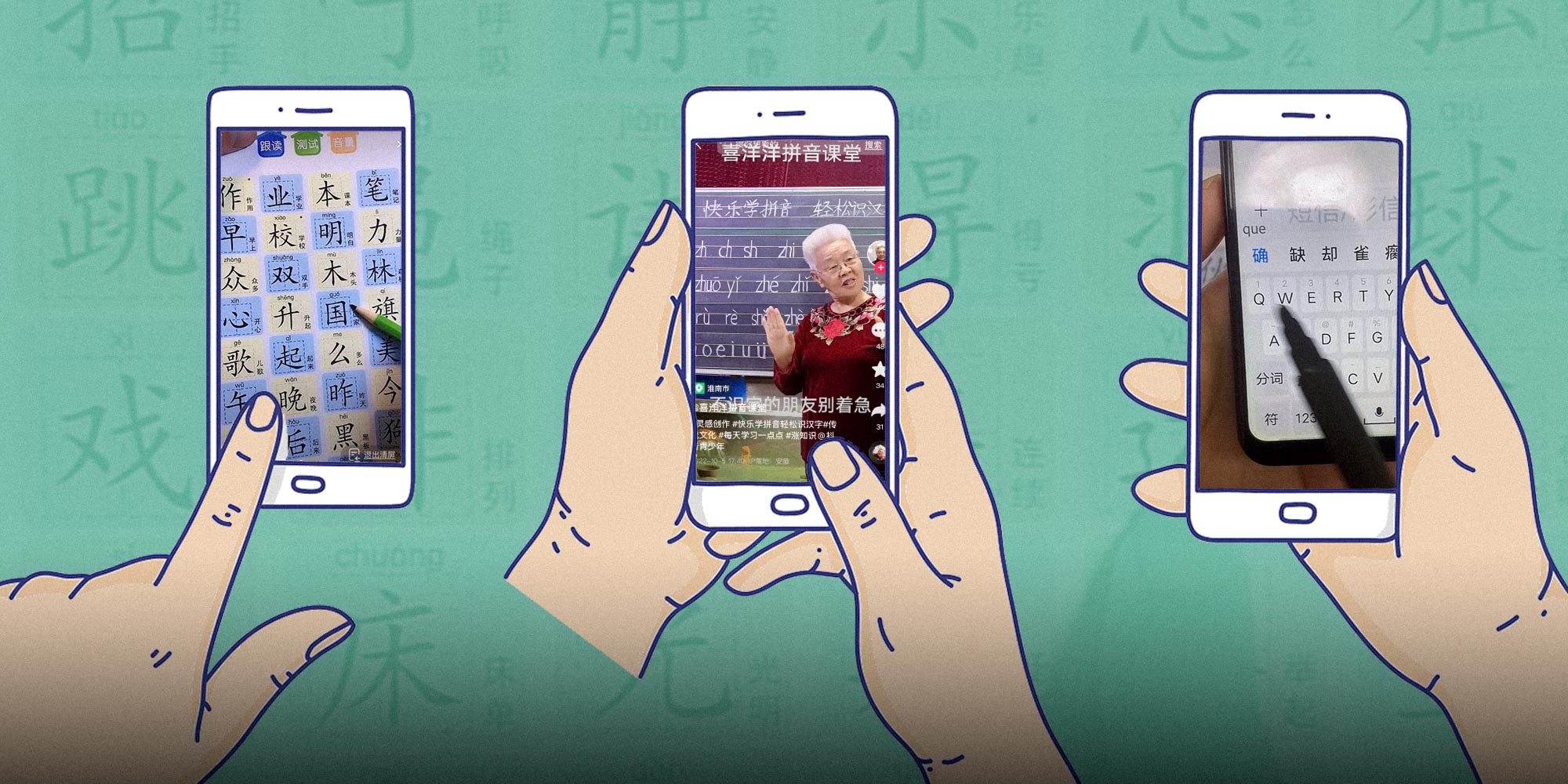

But that’s starting to change thanks to short video apps like Kuaishou and Douyin, China’s version of TikTok. There are now more than 100 people teaching basic literacy skills via livestreamed classes on the platforms. And many of them, including Liu, reach huge audiences.

Liu started giving classes on Kuaishou last May. Originally from the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region — a remote, northwestern part of China with one of the highest illiteracy rates in the country — she was inspired to teach by seeing the deep pain her relatives felt due to their lack of education.

On one occasion, Liu recalls a cousin crying to her that her daughter-in-law was disgusted by her illiteracy, and felt she was unqualified to care for her grandchild. Another relative often complains about how her parents never let her attend school, and how her life could have been so different if she had, Liu says.

Liu herself never finished middle school. As one daughter among six, her education wasn’t a priority for her parents. After she reached ninth grade, they told Liu to come back to the farm and help them raise the chickens, ducks, and geese. “At that time, I didn’t know how to say no,” Liu recalls. “I just secretly cried.”

Previously a small business owner, Liu began experimenting with livestreaming after she stopped working. For her first class, only three people showed up, but she recalls being almost overcome by nerves all the same.

“When I turned on the camera, I was so sweaty that I could barely talk,” she says. “I was afraid that people I knew would see it.”

Over time, however, Liu has become more natural as an instructor, and her audience has swelled. She now has over 43,000 followers on Kuaishou. The majority are middle-aged and elderly women, many of whom — like her — are from large families in western China. But there are also a minority of young men, who often ended up dropping out of school and wandering the streets after a parental divorce or other family traumas, Liu says.

For Liu, it’s purely a passion project: Her online classes are totally free. She does sell extra recorded lessons — along with follow-up homework assignments — for a one-time charge of 98 yuan ($13.40), but she doesn’t make much money from it. In August, she made just 700 yuan in total, she estimates.

Fortunately, Liu’s family are enthusiastically supporting her teaching. Her husband, a driver, believes she’s doing a good thing, and has told her not to worry about making money. Her son and daughter — in college and high school, respectively — have also encouraged her to do what feels right to her, Liu says.

Liu knows that she is far from a perfect teacher. She has no teaching qualifications or professional experience. Before she began giving classes, her own Chinese level was also low. She had to buy a pile of school textbooks and begin studying again — right from the first grade.

But experts tell Sixth Tone that volunteers like Liu can still make a big difference. Jian Xiaoying, a retired professor from China Agricultural University’s College of Humanities and Development Studies, calls the growing number of adult literacy livestreamers a “positive phenomenon,” as they can reach people all over the country.

“Their education level doesn’t matter as long as their teaching is effective,” he says.

For many of Liu’s students, her classes have quite literally been life-changing. Pei Jue, 59, has worked in the hairdressing industry for 30 years, and her illiteracy was a continual source of frustration and embarrassment, she says.

Pei was born and raised in east China’s Shandong province. The second eldest child in her family, she wasn’t allowed to attend school because her parents needed her help taking care of her younger siblings.

Her inability to read became a huge problem when she went into business, as she was unable to withdraw or deposit money in a bank, or sign purchase orders. On one occasion, she paid a heavy price for relying on others to do this for her.

“When I asked someone to save my money for me 30 years ago, they placed it under their name,” recalls Pei, who spoke with Sixth Tone under a pseudonym for privacy reasons. “When I tried to withdraw it, it already belonged to them.”

After that, Pei asked her husband or child to help her at the bank, but her lack of independence in her business activities ate away at her. “It made me sad,” she says.

Since discovering Liu’s classes a few months ago, however, Pei has made huge progress with her reading. She squeezes in study time around her duties at the salon each day, and believes she’s already reached second-grade level. She’s now able to handle bank transactions by herself.

Her husband, who often helps her with her studies, has been impressed by Pei’s transformation. “She studies very hard and enthusiastically,” he tells Sixth Tone. “Sometimes, she even gets up at 3 a.m. and practices writing.”

Sadly, not everyone receives this kind of support. Liu estimates that around half of her students’ husbands are opposed to their wives studying online. Most of her students take her classes in secret, not wanting to be seen by others. “These people feel a deep sense of inferiority,” Liu says.

Yu, a 43-year-old from Ningxia, has been taking Liu’s classes for over three months. But her husband is furious about her studying, and once tore up her notebooks while she was taking part in a livestream class.

In the past, Yu says her husband despised her because of her illiteracy. But now, he appears to resent her learning to read, as it threatens to give her more power in their relationship.

A while back, Yu realized that her husband often wasn’t coming home at night. When she confronted him, he told her he’d been working a lot, and refused to allow Yu to look at the messages on his phone. It was obvious he’d been seeing another woman. So, after he left, Yu took the phone to one of her sons.

“What did your father write to that woman?” she asked. “Mom isn’t able to read.”

What Yu learned horrified her. It turned out her husband had sold the house behind Yu’s back, and had given over 400,000 yuan to the other woman.

Yu has decided to stay with her husband “for the sake of our three sons.” But the incident has hardened her resolve to continue studying. She is urging her two sisters — who also never got a chance to attend school — to join her, but they lack her motivation to learn.

“One of my sisters is 45 and her husband treats her well,” says Yu. “But my husband doesn’t treat me well, so I have to learn.”

For Liu, the hope is that the Chinese authorities can provide more support to help students like Yu. Liu herself still struggles due to a lack of vocabulary, and wishes she could receive training as a teacher. She also thinks it would be great if the government could help organize offline literacy classes during the winter, when farmers are not swamped with farm work.

But for now, the adult literacy livestreaming scene continues to go from strength to strength. Liu has noticed a surge in the number of people providing similar classes in recent months, with some attracting more than 500,000 followers.

Some experts worry the government might even need to step in to make sure the space doesn’t get out of control. Wang, from Beijing Normal University, says that volunteer teachers like Liu can provide real benefits to students, but there’s also a risk that unscrupulous actors will rip off their students.

“Some hosts may have good intentions, like retired teachers, but others may be commercially driven,” says Wang. “It can have negative effects, like making people feel disgusted or angry at adult literacy classes.”

Jian, the retired professor, is also in favor of the government stepping in, setting standards, providing training and guidance, organizing assessments, and setting a maximum price for learning materials.

“It’s against the purpose of educating the illiterate group if the hosts want to take it as a job (and make a living out of it),” he says.

Liu is just heartened by how her lessons have touched people’s lives. On one occasion, a student visited her at home and gave her a leg of lamb as a token of gratitude. Others have sent her messages of thanks, which they had signed themselves for the first time.

“They say it never occurred to them that they could read and write in their lifetimes,” Liu says. “That’s when it hits me that what I’m doing is truly meaningful.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Visual elements from Douyin and kadirkaba/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)