Young Chinese Shrug Off Stigma to Work as Morticians

Most of Cha Quanling’s job involves dealing with the dead.

The 24-year-old from the central Hubei province is responsible for preparing the deceased for their funeral, which includes long hours of sanitizing, cleaning, and oftentimes reconstructing lifeless bodies in the event of accidents. She then speaks with family members about traditions and rituals for the last rites.

Like many of her colleagues, Cha is among the new breed of young morticians joining the funeral service sector. Some say they made this unconventional choice amid a lack of job prospects, while others did it to shift the negative attitudes associated with the job.

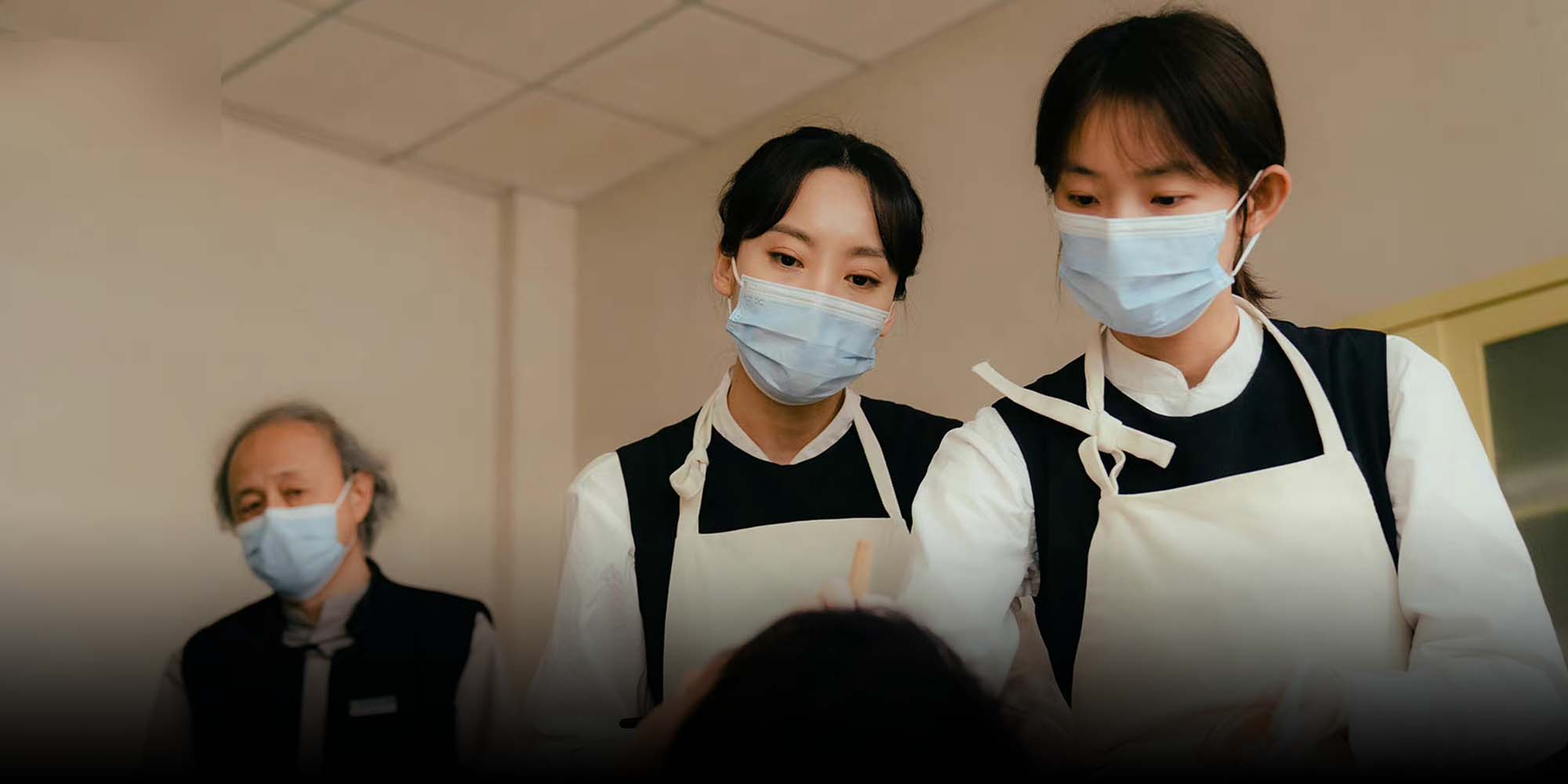

The profession, once mostly invisible to the public eye, has gained more prominence over the past months, thanks to popular productions that are normalizing such “unconventional jobs.” The summer blockbuster movie “Lighting Up The Stars” showed a life-changing encounter between an ex-offender funeral director and an orphaned girl, while the web series “Song of Life,” which concluded Oct. 20, tells the story of a young female mortuary makeup artist who was initially reluctant to take the job but later found it to be a meaningful experience.

“It’s good to see these representations not only educate the public about life and death in an interesting way but also shed light on the real but less well-known pressure and stigma faced by morticians,” Cha said.

Traditional Chinese culture interprets death with a mix of fear and misfortune, so much so that many people try to avoid the use of the number four because its pronunciation sounds similar to death in Chinese. Morticians, particularly, are viewed as harbingers of back luck.

“For example, some funeral attendees will avoid having contact with us, and some drivers will refuse to give you a ride to the mortuary, especially during festive holidays like Spring Festival,” Cha said.

The industry has long been overshadowed by unfriendly attitudes toward morticians, with academic experts estimating that the funeral service sector faces a labor shortage of 20,000 workers annually. Government data from 2021 showed that China has 4,373 funeral service agencies and 87,000 mortuaries who deal with nearly 10 million deaths every year.

But the sector has, however, seen a rapid growth in an increasingly aging society, with the funeral market estimated to reach 411.4 billion yuan ($56.9 billion) in 2026, according to Huaon Industrial Research Institute. The labor shortage, along with an existing demand for workers, has thus attracted fresh graduates struggling to find work in a grim job market.

Tian Anxin, who has worked as a mortician for 10 years, said she has seen more youngsters join the workforce in recent years despite the pervasive discrimination and harassment. She said one of her colleagues was even slapped by a bereaved relative on the job.

The 34-year-old mortician based in the eastern Fujian province told Sixth Tone that she just identifies herself as a make-up artist or an etiquette teacher to stop people inquiring about her job and “avoid any unnecessary troubles.”

“Many people think our work connects mainly with the dead, but in fact it revolves more around the need for the living,” Tian said.

These real-life issues are also portrayed in “Song of Life,” which follows the personal and professional trajectory of its female protagonist, named Zhao Sanyue. The plot weaves in Zhao’s work as a mortician and the biases toward the profession, along with the stories of Chinese families grappling with life and death.

The 13-episode fictional series has racked up 170 million views on streaming platform Bilibili as of publication, with its scriptwriter saying the drama is the result of her personal reflections about life and death amid an aging society and the pandemic. Real-life morticians are meanwhile thrilled to see the representation of their profession on screen.

“It’s comforting to see we’re presented in a really authentic way since it has never happened before,” Zhao Junze, an 18-year-old mortician, told Sixth Tone, adding young morticians like him take more time to know the deceased to orchestrate a more intimate farewell.

With younger and college-educated individuals joining the workforce, those who have worked in the industry for a longer time hope that they will not only help shift the unwelcoming attitude toward the profession, but also modernize the funeral service industry. Many traditional rites have now been largely trimmed — some families prefer their loved ones to be cremated instead of buried, excessive rituals have been minimized, and civil affairs regulators have cracked down on unnecessary fees.

Tian said working as a mortician and witnessing life and death closely has made her more compassionate. She said she now wants to learn more about hospices and caring for those in the final stages of their life.

Meanwhile, Cha plans to use her time after working as a mortician to help people struggling to reconcile with the death of their friends and family members by becoming a counselor.

“I want to comfort both the living and the dead,” she said.

Editor: Bibek Bhandari.

(Header image: A still from “Song of Life.” From Douban)