Almost Real: The Fleeting Fame of Hunan’s Imitation Idols

On July 29 at the Taskin City Plaza, Changsha’s second-largest shopping complex, in the central Hunan province, the vibe was electric.

It looked like a concert featuring any other red-hot idol: ear-splitting cries from a sea of delirious fans mingled with deafening music from the stage. Those at the back stood on the tips of their toes, their phones reaching for the air, lest they miss a single moment of the performance.

The livestreamed show started at 8 p.m., but spectators besieged the stage an hour earlier to get as close as possible. They were all there to see ESO, a local band.

The band’s name itself is a product of China’s shanzhai culture — used to describe anything fake or an imitation, particularly fashion goods. ESO was formed as a satirical knockoff of the hugely popular EXO, a South Korean-Chinese boy band that heralded the age of the idol in the Chinese mainland.

Comprising Lu Ha, Huang Zicheng, and Lin Junjue, ESO’s performances often brim with irony and self-deprecation. And at the concert, it was glaringly obvious.

ESO’s six young members performed in tuxedos. With their awkward dance moves, uncoordinated formations, and clear lack of professional training, the performance was more reminiscent of outdoor karaoke.

But the fans didn’t care much. Between songs, someone in the crowd called out “kiss kiss!” And the band’s shortest and slightly rotund member turned around to smile, put two fingers to his lips, and coquettishly blew two air kisses. It evoked another wave of ecstatic cries.

The concert also marked the premiere of ESO’s first single, “Qingchun Shidai,” or “Age of youth.”

Bilibili vlogger Kang Youwei — his moniker a play on words, written like the name of a prominent modernist thinker during the late Qing dynasty, but using the last two characters of Aiyouwei!, an expression of surprise) — was there that night.

“The people around me were all calling out to the stage. If you call out, sometimes they’ll really respond to you,” he recalls, somewhat starstruck himself.

But the excitement only lasted for around half the show. It was all so comically unprofessional and with many spectators vlogging at the scene, the livestream became increasingly choppy.

“Livestream equipment, sound, mic, all of it, was just no good. I couldn’t make out what they were doing on stage, and I don’t think many else did, either,” says Kang. It eventually got boring and exhausting, and few stuck around for long.

Three hours later, after things quietened down, fans who stuck through to the end followed the idols for more than a kilometer for photos and autographs. Some had no idea about ESO and were there just to get in on the buzz.

For ESO, however, the concert spelled the beginning of the end.

With their vague resemblance to the idols they hoped to imitate, and familiar-sounding stage names, ESO, who formed only last year, had soared to disproportionate fame.

It also came with its own series of dramatic events — one member quit and a live performance was interrupted by urban management officers, both of which trended on social media.

Since the July concert, ESO’s popular member Lu Ha has since dialed back his act for legal reasons, and calls himself Ling Dale. Along with bandmate Huang Zicheng, both have several hundred thousand fans on Douyin, the domestic version of TikTok.

By Aug. 24, at another Changsha mall, ESO had already changed their name to EMO, and premiered a new single called “Wei Zhuang,” or “Masquerade.”

This time, the stage was modest but functional. It included mics, speakers, lights, stage props, and a huge LED screen on which the music video played on a loop. “ESO are now icons of Changsha on the same level as Sexy Tea,” remarked one passerby, referring to a viral local tea chain.

Imitation, unflattering

In Changsha, ESO isn’t the only knockoff group.

Much like how Sexy Tea spawned a series of imitations after becoming an iconic trademark, ESO too has inspired many young livestreamers to follow suit.

It often starts with goofy names.

Much like counterfeit goods that bear logos reading “Dolce & Banana” or “Abibas,” the copycats sound comical almost by design.

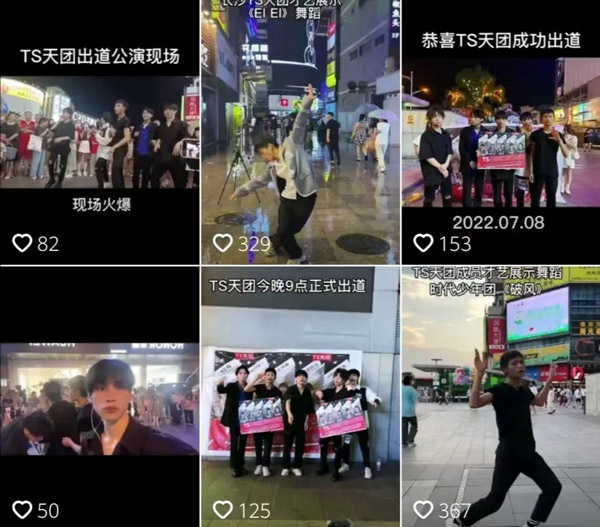

The boy band TSBoys (a parody of the all-star TFBoys, or The Fighting Boys) comprises Hua Chenghui, Cai Zekun, Wang Yuanyuan, and Yi Yangganxi — the latter two riffing on the TFBoys’ Wang Yuan and Yi Yangqianxi, respectively.

The Bulletproof Girls (a parody of BTS, or Bulletproof Boys as they are known in China) are made up of Guan Datong, Liu Erfei, Dili Guoba, and Yummy (imitating leading Chinese female pop stars Guan Xiaotong, Liu Yifei, Dili Reba, and Yang Mi).

Most don’t even have what ESO had: a vague resemblance to the original band. Some don’t even pretend: Yummy is a man.

“We just want the buzz,” says 18-year-old Cai Zekun. Like ESO, TSBoys dances on Changsha’s bustling streets to songs by idol groups. Yi Yangganxi (part of the given name literally means “Dry cleaning”) recalls that the high point was when close to 7,000 viewers tuned in simultaneously.

“They’re obviously singing out of key and can’t dance to save their lives, so why do you keep watching? Many people don’t care, they’re just there to vibe,” says 22-year-old Yangyang, who lives in Changsha and has been to two ESO shows. “It cracks me up. And it’s free of charge.”

Online, some are less enthusiastic. One remark that frequently appears in comment sections is: “The city of Changsha puts up with a lot.”

This new first-tier city, which boasts pop culture success stories like Hunan Television (China’s second-most watched channel) and Sexy Tea, has a thriving entertainment scene. An August report ranked Changsha as China’s second-most influential nightlife economy. A 2020 report shows that 52.6% of daily consumption in Changsha occurs at night.

“Their performances all take place at night, so if you have a typical office job, you can eat dinner at a nearby shopping mall and finish just in time to go see them,” says one fan who has previously attended ESO concerts.

Rags to retweets

TSBoys was born around a dinner table.

A few Changsha-based outdoor livestreamers got the idea of forming a band after ESO was brought up during a casual dinner conversation. On July 8, they debuted at a vacant lot in front of the No. 2 exit of the Huangxing Plaza subway station. They chose this spot since so many people walk across the area every day.

Early on, band leader Hua Chenghui, which literally translates as “turned to ash,” posted a video on Douyin that got 543 likes. Someone replied, “Go back to tightening screws at the factory. You guys aren’t half as good as ESO.”

The disdainful remark alluded to a snippet Lu Ha once shared about him being a migrant factory worker from the eastern Jiangxi province. All of ESO’s members grew up in rural China.

“Poor kids usually go into one of three lines of work: hairdresser, cooking, or automobile repairs,” observes TSBoys’ Cai Zekun, who was born in a village outside Zhuzhou, in the central Hunan province. His bandmate Yi Yangganxi, 22, is from rural Sichuan. Both worked as hairdressers.

After three years, Yi Yangganxi got bored with the repetitive nature of work in the salon and found himself a new job in Chongqing as a real estate agent, which he stuck with for a year.

Selling houses, he made about 7,000-8,000 yuan ($950-$1,100) a month. But it was clear from the beginning that there wasn’t much scope for growth.

“I was 20, so there was a lot I didn’t know how to handle. Brushing shoulders with successful people was stressful — you just feel inferior,” says Yi Yangganxi.

Livestreaming, on the other hand, looked more promising: “If others can do it, why couldn’t I?”

But without a recognizable face or personality, and all one can do is chat online and perform songs, it’s hard to truly make a name.

In April, Cai Zekun discovered that videos of pop idol Cai Xukun playing basketball were popular. He bought a similar pair of overalls and imitated him dancing and rapping while playing basketball.

He also learned one of the star’s hit songs. They look nothing alike, but with Cai Zekun’s knack for vibing, the view count surged. “In the past, I’d maybe get 15 or so people in a livestream. After that video, there were at least 2,000 at any moment.”

The moniker Yi Yangganxi was chosen by Hua Chenghui. At first, Yi, who goes by just Ganxi now, didn’t realize that it was a parody of TFBoys’ Yi Yangqianxi, known in English as Jackson Yee.

“Jackson Yee is not bad. I’ve seen a couple of his movies,” says Ganxi. He was very clear about his objective. “I adopted the name to get more views.”

Though he doesn’t imitate Yee in any of his livestreams, that didn’t stop him from trending on the microblogging platform Weibo after shooting a video with ESO.

Contrary to speculation at the time, he didn’t join ESO. However, the experience, he says, “Did give me my 15 minutes of fame.”

To win more fans, band members attempted to learn dancing. Ganxi says that he spends around 40 minutes a day following the most popular dances on Douyin and has begun work on basic moves seriously.

Now, he’s grown used to the comments in his livestream:

“So ugly.”

“Can you do anything well?”

“Cringe. Don’t quit your day job, dry cleaner.”

Sometimes, he cooks while doing the “social shake” or speaks in a funny voice. “It’s all to make people happy, again for the views,” he says.

Given China’s ongoing reckoning concerning its biggest-earning entertainment stars, the knockoff idols on the streets of Changsha serve as symbols with which to have some cheap fun. It echoes the discontent and ridicule people associate with the industry.

“I don’t have sympathy towards those ‘real’ celebrities who rake in astronomical sums,” commented one netizen on a video related to ESO. “If only they put in a bit of effort, I wouldn’t be so into this ESO stuff.”

To ESO fan Yangyang, pop idols neither work hard enough nor connect deeply with fans.

Thus, a small clique of young people fooling around and referencing memes in their livestreams has drawn a larger, equally young audience who poke fun and banter as they watch. Whether cheering or jeering, it all contributes to the knockoff bands’ notoriety.

But it’s not all fun and games, since legal troubles can often follow.

On August 12, China News Network reported that ESO is likely liable for copyright infringement. One lawyer quoted in the report said that the imitation constituted “trademark confusion,” a form of unfair competition.

Just three days later, the members of ESO changed their names and, in videoes, apologized to fans of EXO. Lu Ha reverted to his birth name, Ling Dale; a week later, the band rechristened itself EMO.

Since then, the drama has tapered off. Most recently, Ling Dale quit the group and moved to Guangzhou 700 kilometers away.

On returning to Changsha, Ling gathered everyone and held a farewell concert. While many fans attended, the crowd was but a shadow of what the band saw just a month before.

TSBoys and Bulletproof Girls have since split up too.

Yi Yangganxi changed his name to just Ganxi, while Cai Zekun now goes by Ze’an. In August, the two left Changsha for Chongqing. Says Ze’an, “Changsha is saturated now. Too many vloggers doing the same thing, it’s hard to get ahead.”

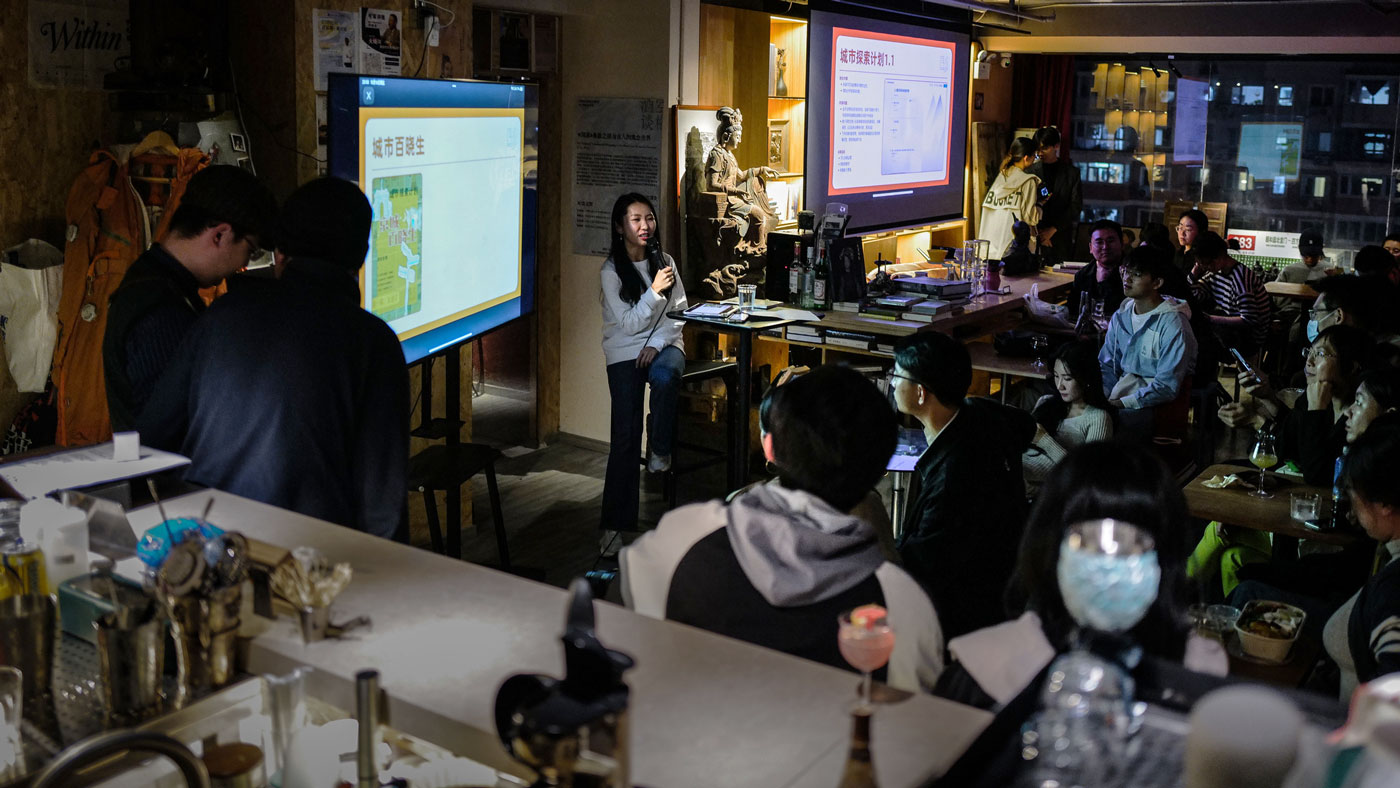

Changsha cyberpunk

According to a July report in the Hunan Daily, there are more than 100,000 new media professionals in Changsha — this includes livestreamers and vloggers.

Twenty-four-year-old Wanzi recently relocated from her home city of Nanchang, in Jiangxi, to Changsha hoping to make it big in the livestreaming business.

She often chooses the same outdoor location — the foot of a bridge spanning the Xiang River — because the few streets clustered with hot spots are crowded, and urban management officers keep a strict watch.

Even under this bridge, there are usually three dozen other vloggers furiously at work under the streetlights, talking into phones mounted on tripods.

A-Long, who has two years’ experience running livestreamers for a multi-channel network company in Changsha, estimates that around 30% more livestreamers have signed up this year compared with 2021. “It yields large returns for a small investment. With a phone, you can do it anytime, anywhere. There’s room for growth,” he says.

He is aware of ESO, but says he doesn’t approve of them. “How they dance, what they say, it’s pretty clear they are just after cheap laughs.” He believes that even when it comes to imitation, historical figures like the Chinese war god Guan Yu and the famed ancient beauty Diaochan are better targets, allowing for more innovation.

Compared to ESO, there are far more extreme vloggers out there. Some netizens refer to Changsha’s Huangxing Road at 3 a.m. as “night of the living dead.”

In such large commercial and shopping districts, it’s not uncommon to witness the bizarre: young men and women holding their phones and occasionally screaming out “Everyone, vote for me!”; some crawling on the ground and yapping like a dog; some wearing a crop top and gyrating frantically; or even some diving into trash cans.

Beginning in 2021, Changsha started to maintain an official list of outdoor vlogger accounts, and launched three separate campaigns to clean up the busiest districts. Now that the government is watching, vloggers know when they need to dial it down.

For her most recent livestreams, Wanzi stayed far away, so she wouldn’t invite civilian complaints to the authorities. She also mentioned in a livestream that she wouldn’t cross the line if she lost a live battle — where vloggers sometimes play competitive, often borderline menacing games against each other. “Or my account will get shut down,” she underscores.

“Changsha really is a tolerant city. Otherwise, why would so many vloggers come here?” says Xiaofan, who has worked in the industry here for seven years. She believes that, though locals find some of the content “cringeworthy,” they’ve become indispensable.

“Changsha can’t be without vloggers, just like the West can’t be without Jerusalem,” she says, referencing a popular meme from the Chinese historical film “My 1919,” about the May Fourth Movement.

She adds, “It contributes to the economy, and makes the streets livelier. You can see them along West Jiefang Road, holding their phones as they walk, saying, ‘This is the sleepless city of Changsha. Let me show you around.’”

In the early hours of the morning along a busy street, a man wearing a thick gold chain and a woman wearing a schoolgirl-like pleated skirt “battle,” while just two meters away, a street performer sings the latest “god song” from Douyin.

All the while, neon lights shine on the excited and curious faces of passersby; the air brims with laughter, cries, singing, and the smell of alcohol and spicy food.

“This is hardcore cyberpunk,” someone remarked after seeing it all.

It begs the question. After the incredulous fame ESO enjoyed, who will be the next subversive act to come out of Changsha?

Reporters: Qiu Yumin and Yang Xiaotong.

(Yangyang, A-Long, Wanzi, and Xiaofan are pseudonyms.)

A version of this article originally appeared in Oh! Youth (36Kr). It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Zhi Yu and Apurva.