The Wild and Wooly History of China’s Panda Diplomacy

Another four-year World Cup cycle is drawing to a close, and China’s soccer squad will once again be watching the excitement from their couches.

China won’t be entirely absent from the festivities in Qatar, however. Its soccer team may not have scored an invite, but two representatives of a far more successful national team touched down in the Middle Eastern country late last month. Arriving just in time for the World Cup, Sihai and Jingjing are the first giant pandas ever loaned by China to a Middle Eastern nation; if all goes well, they will represent their home country in Qatar for the next 15 years.

China’s strategic utilization of pandas as tools of public diplomacy is by now well known. This “panda diplomacy” has been a resounding success, helping put a fuzzy and friendly face on China at zoos around the world for more than 70 years. But the highly choreographed arrival of Sihai and Jingjing in Qatar is a more recent development. In its early years, China’s attempts at panda diplomacy were often reactive, even haphazard, and officials struggled to determine the best way to allocate one of the country’s rarest natural resources.

The world’s love affair with pandas dates back to 1936, when a panda cub named Su-lin arrived in the United States. Five years later, then-First Lady of the Republic of China Soong Mei-ling presented a gift of two additional pandas — Pan-Dee and Pan-Dah — to the Bronx Zoo in honor of American assistance during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Although not the first pandas to arrive in the U.S. — Pan-Dah and Pan-Dee were actually replacements for an earlier pair procured by the Bronx Zoo through other channels — Soong’s gesture marked the first time the Chinese government formally gave live pandas to a foreign country as a gift. The move was a resounding success: The pandas were feted by an enraptured American public and provided a much-needed boost to China’s ongoing efforts to win over U.S. public opinion.

Panda diplomacy took a sharp leftward turn after the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, however. In line with its diplomatic strategy of “leaning to one side,” the new government went out of its way to satisfy the demands of fellow socialist nations while remaining on its guard toward any capitalist rivals, whose demands it would, to the greatest degree possible, either put off or refuse.

Panda diplomacy thus became subject to the needs of socialist solidarity, and in 1957, Beijing mayor Peng Zhen offered to send a panda to Moscow as a gift to the Soviet people.

There was just one problem: an acute shortage of captive pandas.

Capturing pandas had never been easy. Teams of animal experts and local villagers might spend several months stalking through the precipitous mountain ranges of the southwestern Sichuan province to no result. In 1957, the Beijing Zoo had just three young pandas, all captured in Sichuan the year before. After Soviet head of state Kliment Voroshilov’s 1957 state visit to China, plans were made to present a pair of them, Pingping and Qiqi, as national gifts to the Soviet Union.

A year later, the Soviet Union returned to China with an unexpected request. Declaring that both of the gifted pandas were male, the Soviets asked China to replace one of them with a female panda, in the hope that the pair would mate and produce offspring.

At the time, even experts barely understood panda anatomy, and China deferred to their allies. In 1958, the U.S.S.R. sent back Qiqi and was gifted another panda, An’an, to take its place. The trade proved ill-advised. On closer inspection, An’an turned out to be male, while Qiqi was found to be female.

Aside from the Soviet Union, the only other country to be gifted a panda by the Chinese government during the 1950s and ‘60s was North Korea, which was the recipient of five live giant pandas between 1965 and 1980. Sadly, all five died prematurely or went missing due to their hosts’ poor rearing practices.

Meanwhile, it was all but impossible for Western countries to get their hands on a panda. After 1949, Britain, the United States, and West Germany all wrote to China in the hopes of acquiring one, whether by purchase, exchange, or even being given the chance to capture one themselves. Most of these proposals were rejected on political grounds; a few failed because China simply didn’t have enough pandas to give. Nevertheless, Western countries’ panda fever led them to keep looking for ways to circumvent China’s diplomatic barriers.

Their most successful attempt came in 1958, when the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago commissioned Heini Demmer, an Austrian animal trader, to buy or exchange pandas from China on its behalf. After negotiations with the Beijing Zoo, Demmer brokered a trade: one panda for three giraffes, two rhinoceroses, two hippos, and two zebras. The panda he received in return was Qiqi, who had just been sent back by the Soviet Union.

Belatedly confirmed to be female, the Beijing Zoo renamed her Chi-Chi before trading her away. But Chi-Chi’s planned arrival in the U.S. fell apart almost immediately. Due to an export regulation law issued by the American Department of Commerce, the panda’s entry into the United States was denied on the grounds of her “Communist background.” Left holding the bag, Demmer took Chi-Chi on a tour of Europe until the London Zoo agreed to adopt her for 12,000 pounds (roughly $390,000 in today’s money).

The whole of England was instantly enraptured by Chi-Chi’s arrival. As her fans tracked her every movement, her handlers became increasingly concerned about her biological clock. Where could they find Chi-Chi a suitable mate?

With China and North Korea off the table, there was only other country in the world they could turn to: the Soviet Union.

Pingping had died of illness in 1961, but An’an was alive and well in Moscow. After a year and a half of high-level negotiations, Britain and the Soviet Union finally agreed to set their pandas up on a date, and in March 1966, Chi-Chi boarded a private jet for the Soviet capital. Once there, surrounded by veterinarians and officials from both the London and Moscow zoos and under the watchful eye of remote-controlled television cameras, nine-year-old Chi-Chi met her betrothed.

Alas, rather than fall madly in love, the pair were immediately at each other’s throats. A second attempt was made two years later, this time in London, but nine months of living in close quarters failed to bring them any closer together.

As Chi-Chi’s chances of producing descendants grew slimmer, the West fell into a state of anxiety. Just as people were beginning to lose hope, salvation arrived in the most unlikely form: American president Richard Nixon. On his groundbreaking February 1972 visit to China, Nixon expressed his wish that China would gift a pair of pandas to the American people. In the spirit of thawing relations between the two countries, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai agreed.

A few months later, Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing arrived in the U.S. by private plane. The first pandas to set foot on American soil since 1953, more than 8,000 members of the public braved the rain to greet them at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C. In the first month after their pavilion opened to the public, the pair received more than one million visitors.

Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing’s arrival in the U.S. ushered in a boom period for panda diplomacy. Later that same year, two more pandas, Kangkang and Lanlan, were gifted to the Ueno Zoo in Japan to mark the restoration of diplomatic relations between China and Japan. The pair drew millions of curious visitors over the course of the 1970s, and when Lanlan died in 1979, her unborn baby still in her womb, thousands of Japanese made a pilgrimage to their enclosure to pay their respects.

Between 1972 and 1982, China would donate nearly 20 giant pandas to countries around the world, acts that greatly improved China’s international image. But the downsides of this panda diplomacy were becoming hard to ignore. International critics argued that the strategy ran counter to the 1975 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. The backlash continued to build after a November 1979 series produced by the China People’s Broadcasting Station shed light on how China was capturing its giant pandas.

Faced with mounting criticism, the Chinese government announced in 1982 that it would stop giving pandas to foreign countries. Since 1984, the pandas you see in zoos around the world have mostly been rented, with a portion of the fees generated by these agreements plowed back into panda conservation and research. Today, determining a panda’s sex is no longer a problem, and most of the difficulties involved in getting them to mate in man-made environments have essentially been overcome.

Thanks in part to these advances, giant pandas aren’t quite as scarce as they used to be. In September 2016, the conservation organization IUCN downgraded them from “endangered” to “vulnerable.” Yet their rarity abroad means they remain a prized get for any zoo. In preparation for Sihai and Jingjing’s arrival, the Qatari government built a lavish air-conditioned pavilion for their exclusive use, with plans to open it in time for the influx of visitors brought by the World Cup. It’s further proof, if any was needed, that no one conducts diplomacy quite like a panda.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

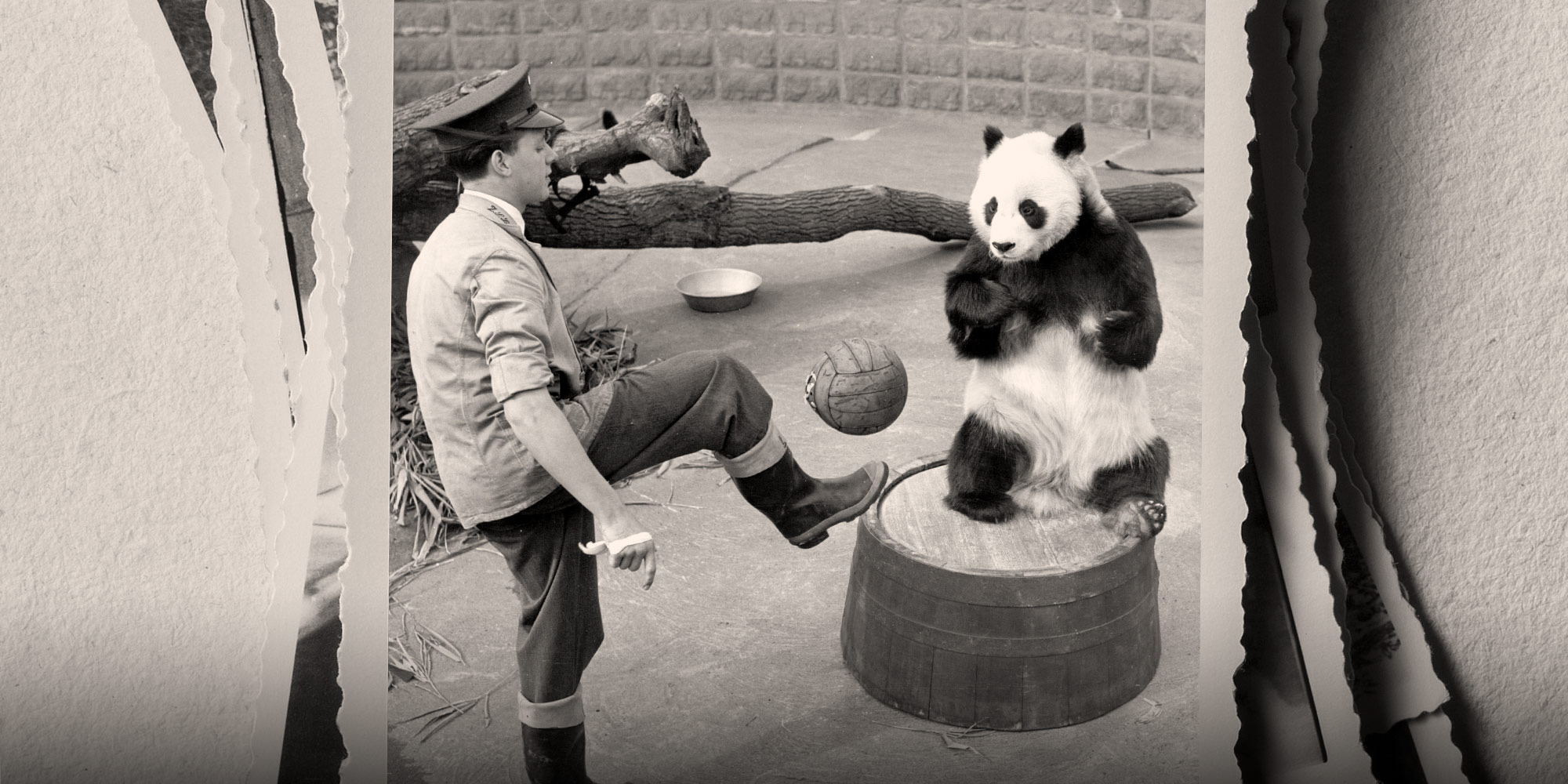

(Header image: Alan Kent, Chi-Chi’s keeper, plays a game of football with the panda at the London Zoo in May 1959. Fox Photos/Getty Images via VCG)