How Academic Tracking Exacerbates Rural China’s Education Gaps

For all the attention paid to the gaokao college entrance exam, Chinese students’ futures are often decided not by an exam score, but by a class roster.

Most Chinese middle and high schools sort students into classes based on their academic performance or perceived potential. Growing up in the countryside, my high school offered two tracks: honors classes and regular classes. In interviews with rural Gen-Z children at top universities, many said their high schools now divide students into three levels: honors classes for top performers, “experimental” classes for average students, and regular classes for students with the lowest grades.

The earlier tracking starts, the starker the divisions that result. Xu, a 21-year-old student from a rural household, recalled that all the students in her middle school honors class had progressed on to an academic high school, but that wasn’t the case for others at her school, many of whom went to vocational high school instead. “Our two honors classes had a really strong learning environment, but the school cared less about the other classes, and so did parents,” Xu said. “It’s a mob: There’s fighting, smoking, drinking, people doing their hair, and dating. Whatever you can think of, they do it.”

The stakes are particularly high in the countryside, where chronic shortages of educational resources funnel top students into a handful of “key” schools in county seats or small cities. The high schools that have better resources and stronger reputations attract more and better students, which in turn nets them more funding and resources and widens the gap between students at key schools and everyone else.

The reputation of these key schools usually hinges on students’ grades and their graduates’ admission rates into top universities. In an attempt to get ahead of competitors, some county and city high schools recruit top students before they even take the high school entrance exam. A student named Ma, for example, said she was able to skip the high school entrance exam by taking a separate exam offered by a local high school. The top 80 students across the county were offered early admission into the school’s most competitive class.

Chen, a hardworking student from the southwestern province of Guizhou, said his recruitment began at the elementary level, as a county-level middle school offered him early admission and access to its superior learning environment and resources. Later, both the city and county high schools also recruited him heavily. The county high school even promised three years of free tuition, 2,000 yuan ($280) in annual stipends, and other scholarships. Xu also had had a similar experience. Having tested well on the high school entrance exam, the city high school offered her an annual subsidy of 8,000 yuan, along with other perks like honors housing and honors classes.

This system works well for high-achieving rural students, as schools concentrate their resources on kids who have the best chance of getting into top schools. Schools also privilege top students in other ways: elevating them to be class leaders or class representatives, allowing them to give talks beneath the national flag, showering them with attention, or assigning them to preferred dorms.

All this is paid for by squeezing their classmates, however. The gaps both between and within schools are well known to rural parents. Families with means have responded by doing everything they can to get their kids on the right track, including quitting jobs to take care of their children and help them with their studies; buying a house in town to get a guaranteed spot at a particular school; and even offering bribes for admission into better programs. Their hope is to get their children out of the village as early as possible and into better schools in town so that they can have a brighter future.

The result is a vicious cycle, as underfunded schools struggle to attract and retain high-achieving students, resulting in even more families choosing to send their kids elsewhere. One of my interviewees was an only child from a rural part of the southeastern Fujian province. He attended elementary school in his village for a year, but as soon as his parents had saved enough to buy a house in the city, they transferred him to an urban school. “Every rural person knows that you have to go to school outside of the village to have opportunities,” he said. “We went back to visit in 2020. Everyone used to go to that elementary school in our village. This year, it only had 6 students.”

This is the second in a series on rural education in China. Part one can be found here.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell.

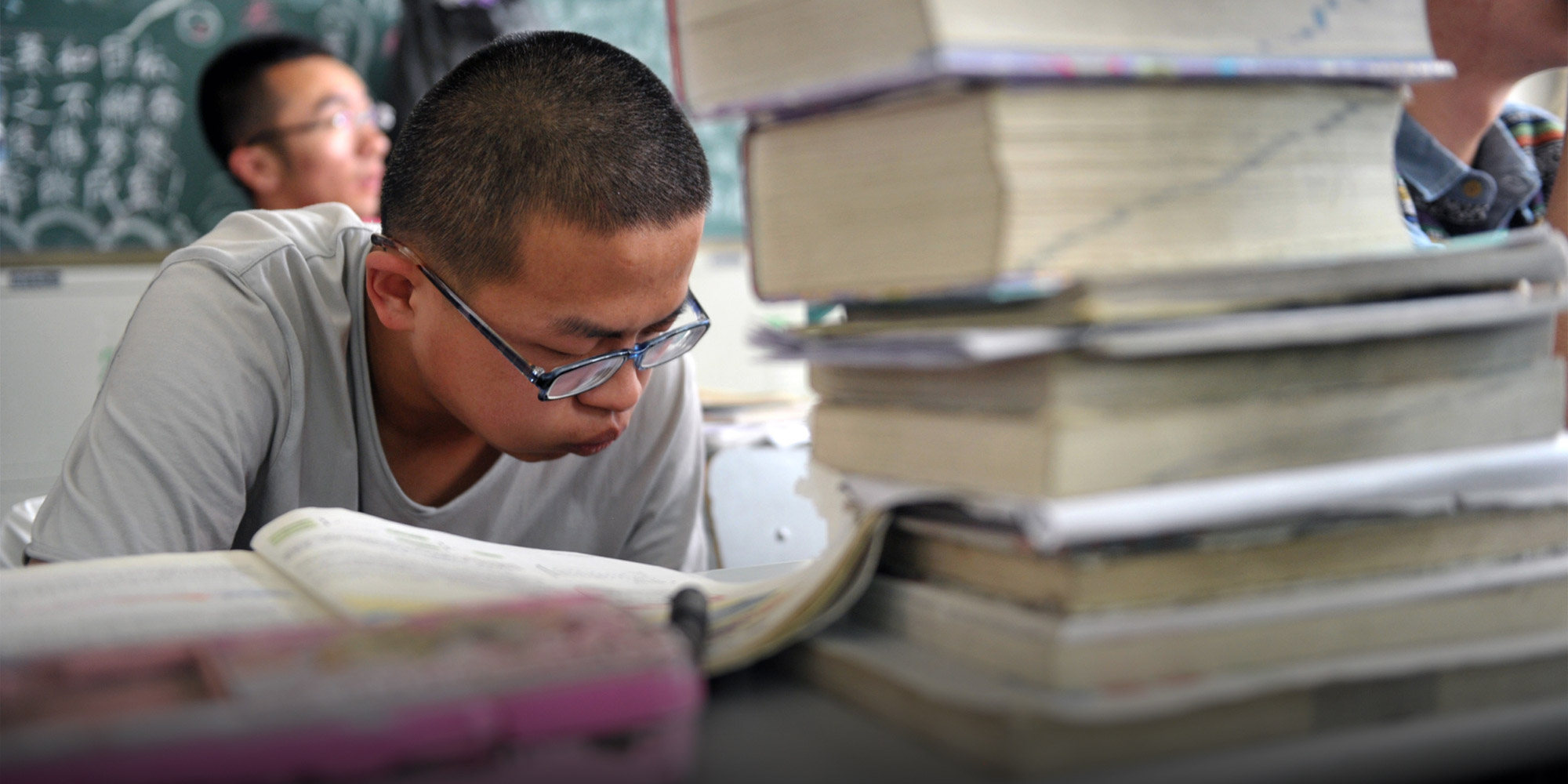

(Header image: A senior prepares for the “gaokao” at a high school in Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, 2013. Wu Xiaoyu/VCG)