COVID Is Spreading Explosively in China. Can Its ICUs Cope?

It has now been more than two weeks since China abandoned most of its “zero-COVID” restrictions. Though it’s impossible to know how many people have been infected in recent days, one thing is clear: The virus is spreading explosively.

Up to 10 million people may have already contracted COVID-19 in Shanghai alone, local health experts estimate. On Chinese social media, users have been posting about their symptoms in droves. COVID memes have become a dark new social media trend.

But things are only going to get harder as the virus continues to spread. A paper published in the scientific journal Nature Medicine in July 2022 predicted that if China allowed its entire population to be infected with Omicron, it would lead to 5.1 million (non-intensive care) hospital admissions, 2.7 million intensive care unit admissions, and 1.6 million deaths within three months. That is almost the same number of deaths caused by the four most lethal cancers in China in 2020.

The death toll will depend in part on how many patients are able to access emergency treatment — especially ICUs. But how overstretched will these facilities become as China’s COVID wave peaks? The data is far from clear.

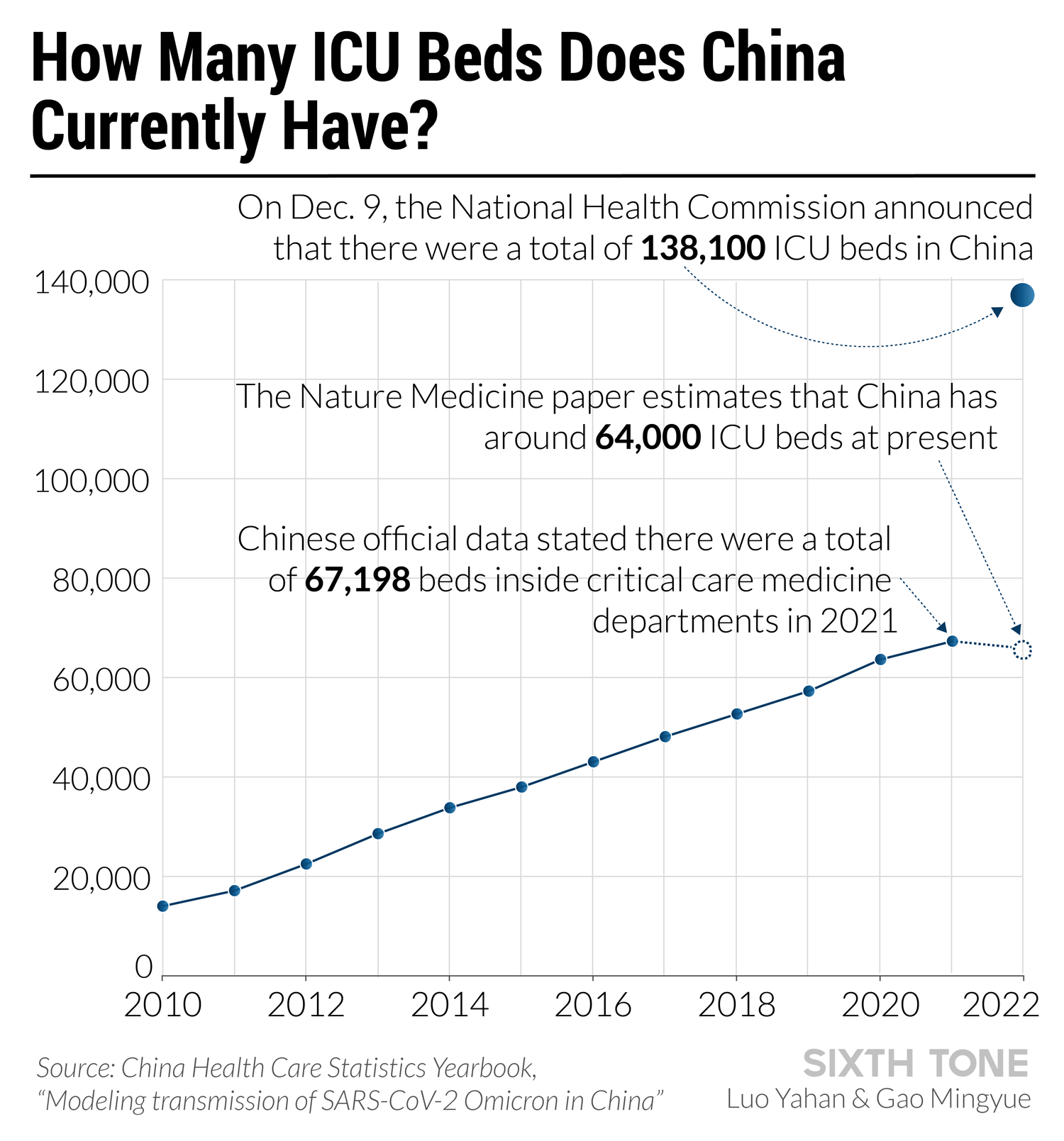

The Nature Medicine paper states that the peak demand for ICU beds will reach 1 million in China. That is 15.6 times more than the number of ICU beds available nationwide, which it estimates to be around 64,000.

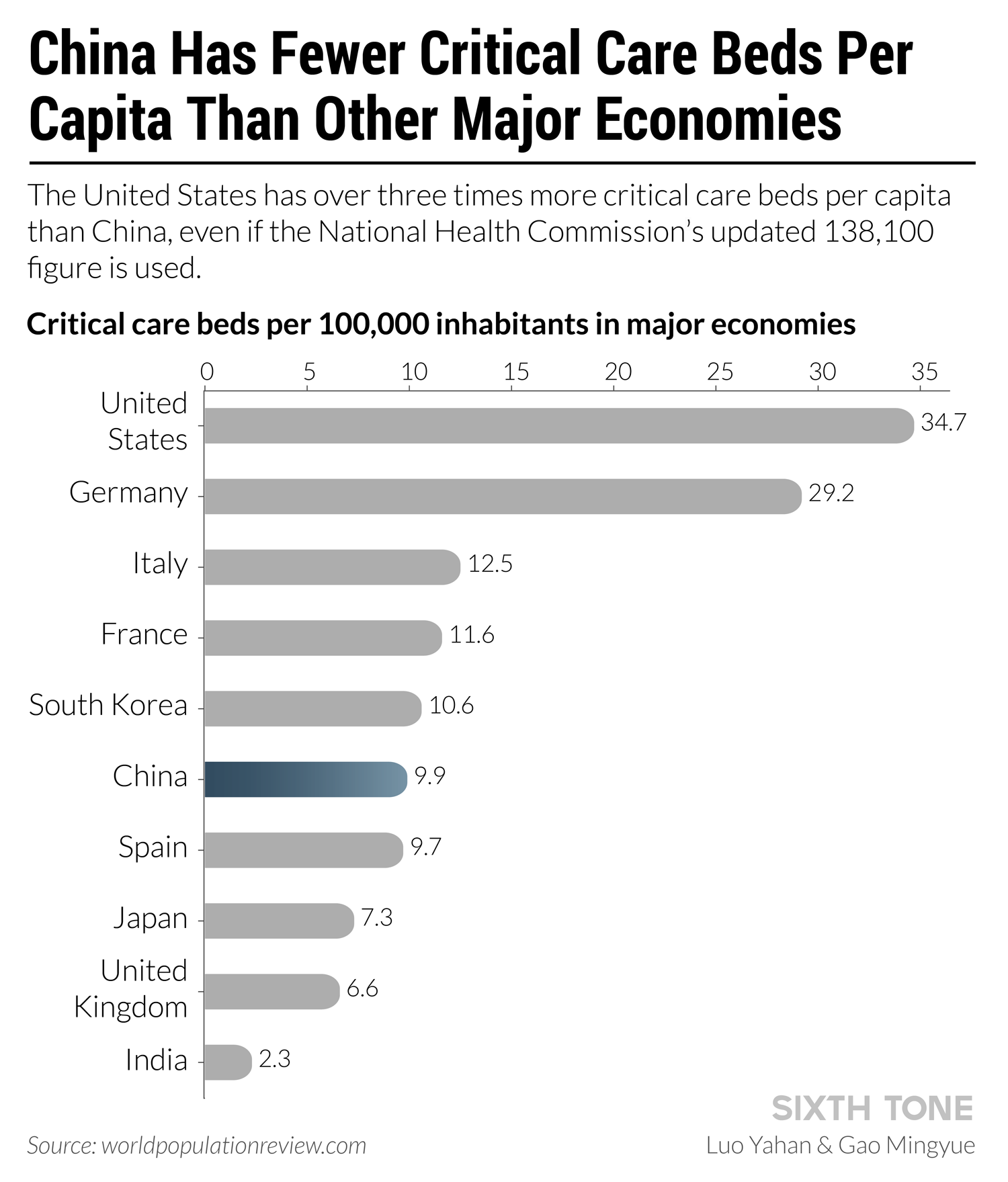

However, the Chinese government disputes this number. On Dec. 9, 2022, the National Health Commission announced that there were a total of 138,100 ICU beds in China — more than double the paper’s estimate.

It’s unclear how the authorities arrived at the 138,100 figure. At the end of 2021, there were only 67,198 beds in critical care medicine departments inside China’s hospitals, according to the 2022 China Health Care Statistical Yearbook. The National Health Commission had not responded to Sixth Tone’s request to clarify the discrepancy between the two figures by press time.

One possible explanation is a difference in classification. A post on the Chinese investment platform Jiuyangongshe, which is no longer publicly accessible, stated that only around half of the ICU beds inside Chinese hospitals are located in critical care medicine departments: The others are located in other departments. So, the Dec. 9 ICU beds figure may be the sum of the two.

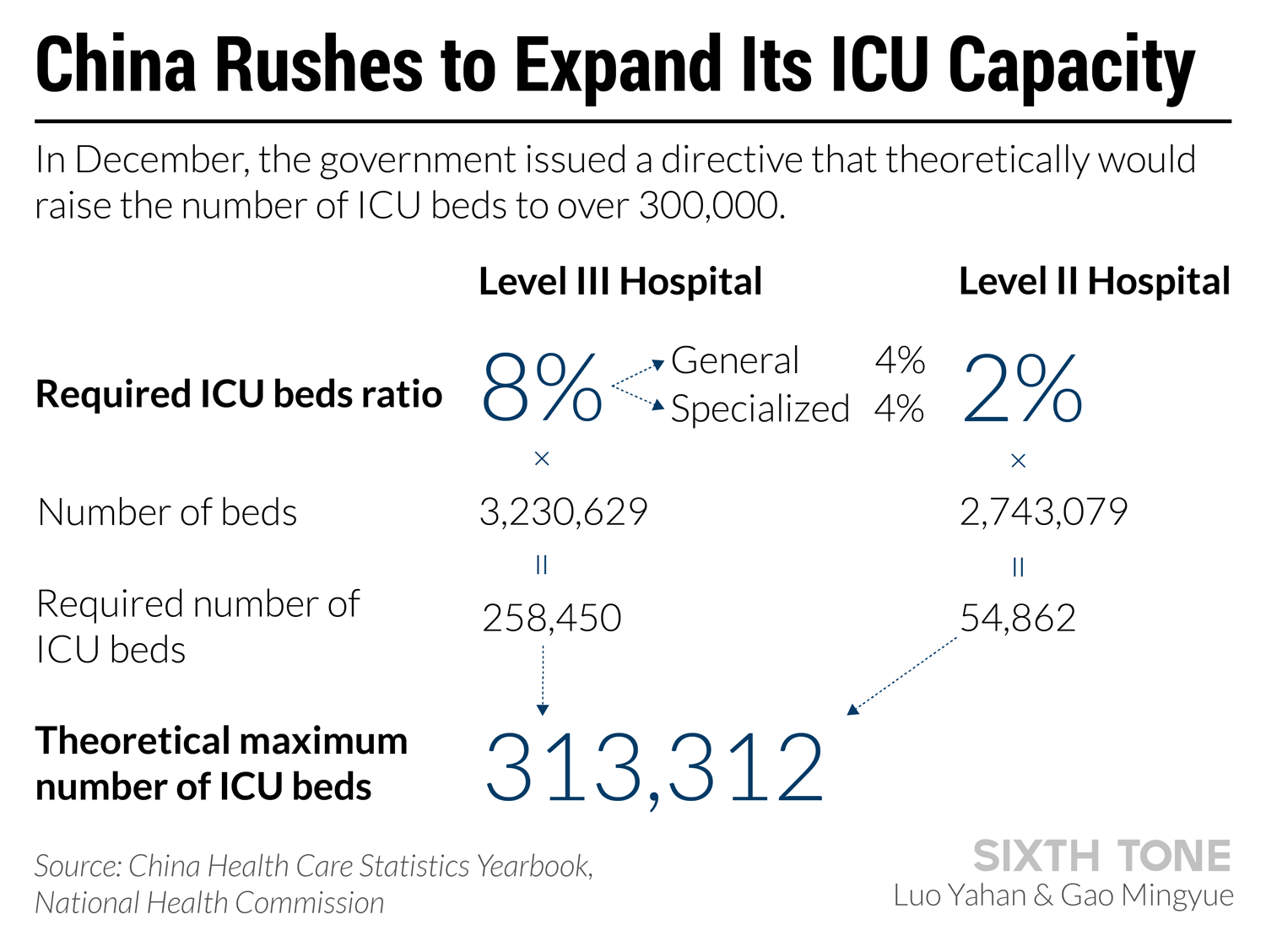

The authorities, however, are aware that even 138,100 beds will be far from enough. Also on Dec. 9, two days after the pandemic-control restrictions were loosened, the National Health Commission announced a series of policies to expand the country’s ICU capacity. All Level III hospitals were ordered to ensure that 4% of beds were equipped as ICU beds inside critical care medicine departments, and to prepare another 4% as backups in other departments.

If every hospital successfully complies with this directive — and all the other regulations announced so far — this would theoretically lift China’s total number of ICU beds to over 300,000. That is more than quadruple the original 64,000 estimate, and would make it far easier for Chinese hospitals to cope with the predicted peak demand of 1 million ICU admissions.

But in reality, it’s highly doubtful that hospitals will be able to prepare that many ICU beds in time. The government originally set a deadline of the end of December for the directive to be implemented, giving hospitals 20 days to comply. Public records, however, show that Chinese hospitals typically need at least three to four weeks to procure new equipment.

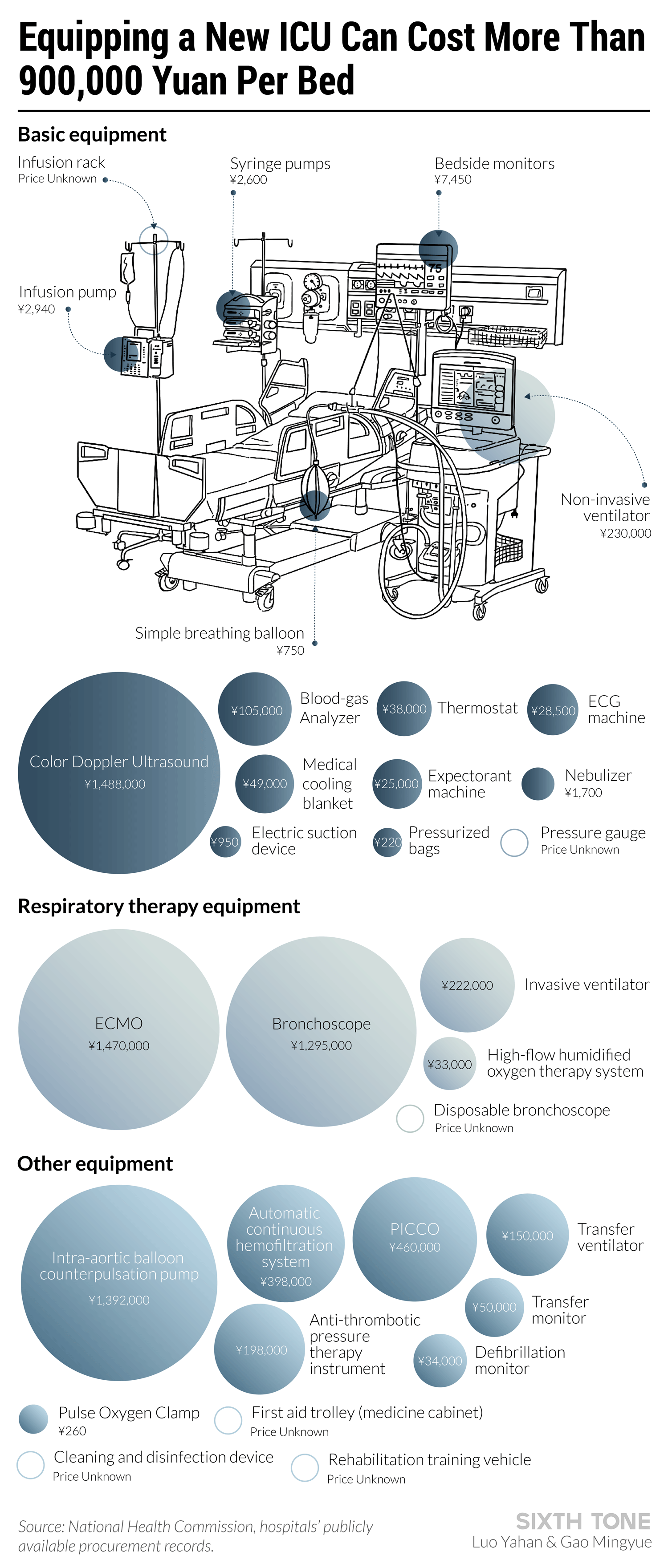

What’s more, converting an ordinary hospital bed into an ICU bed is costly. The medical equipment needed to set up a new ICU can cost more than 900,000 yuan ($131,000) per bed, according to Sixth Tone’s calculations based on National Health Commission data and hospitals’ publicly available procurement records.

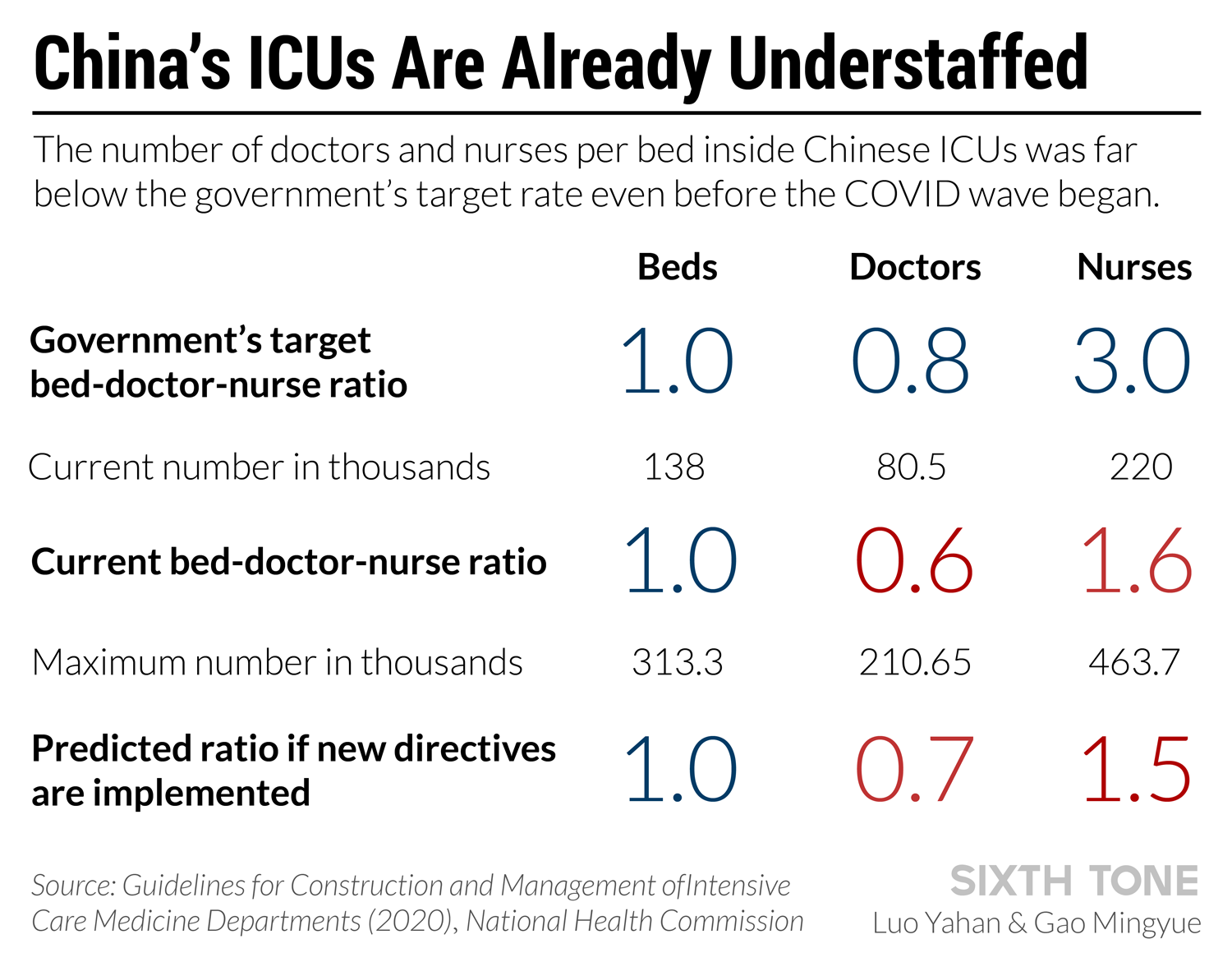

Then, there is the challenge of staffing these new ICUs. Even if hospitals are able to quickly procure new equipment and convert wards into ICUs in record time, will there be enough medical workers to run them? Installing a new ventilator is far easier than recruiting a new nurse.

China’s ICUs are already understaffed. According to data released by the National Health Commission, the bed-to-doctor and bed-to-nurse ratios inside the country’s ICUs are currently 1:0.58 and 1:1.59, respectively, which are far below the national targets of 1:0.8 and 1:3 set in 2020.

If hospitals hit the government’s ambitious new targets for expanding their ICUs and medical staff, the bed-to-doctor ratio will slightly improve, but the bed-to-nurse ratio will further decrease to under 1:1.5.

And if large numbers of health workers become infected, the understaffing issue will only worsen.

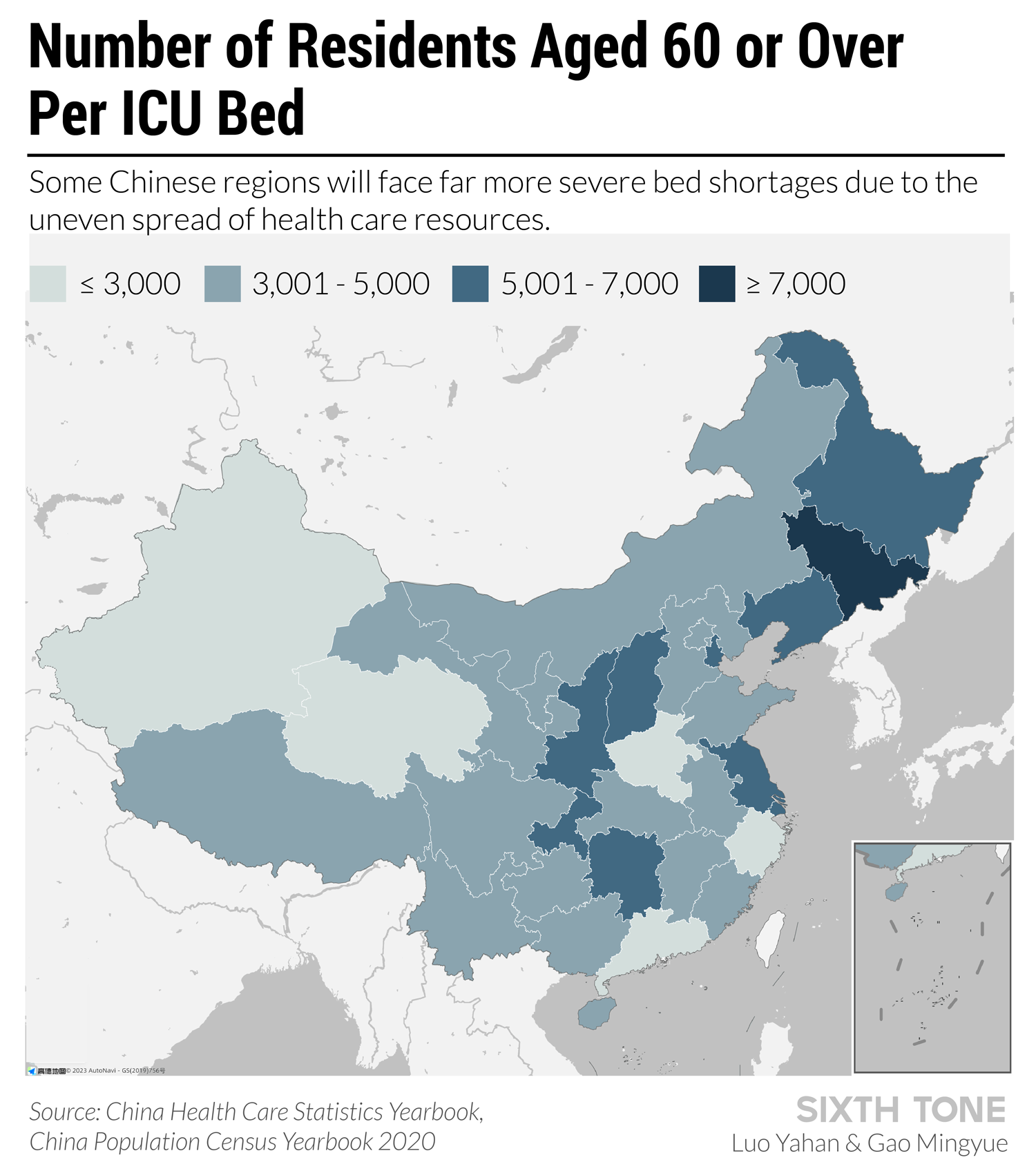

In addition, some areas will face a more severe shortage of beds due to the uneven spread of health care resources across the country. In Hong Kong, which faced a huge COVID outbreak in early 2022, there is one ICU bed for every 3,800 local residents aged 60 or over. Much of the Chinese mainland has far fewer. In the northeastern Liaoning province, there is only one ICU bed for every 11,000 seniors.

There are already signs that China’s hospitals are under pressure. On Dec. 27, a National Health Commission spokesperson said that critical care wards in some provinces are approaching full capacity, and that hospitals need to further expand their ICUs or accelerate the turnover of patients.

Even countries with far greater health resources than China have struggled to cope with large-scale COVID outbreaks. The United States ranked first worldwide for the number of critical care beds per capita at the start of the pandemic. Yet by November 2020, some hospitals reportedly became so overwhelmed that they were unable to provide emergency care for patients with heart attacks.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Medical staff work inside an ICU at Xiangya Hospital, in Changsha, Hunan province, Jan. 3, 2023. Yang Huafeng/CNS/IC)