The Forgotten Romantic Who Became Britain’s First Sinologist

When we think of great early Western scholars of Asia, Thomas Manning’s name does not come up in the same sentence as William Jones or Jean Francois Champollion. Yet Thomas Manning pursued fame with relentless self-confidence and energy. In the end, fame didn’t so much elude him as cease to interest him.

As a young man, Manning set himself an especially challenging life goal, to become Britain’s first Sinologist. No one in Britain spoke Chinese, nor were any books or manuals available. The Macartney embassy of 1793 to the Qianlong emperor had relied on Chinese Catholics from the Vatican for interpretation, requiring the English to speak Latin. The Continent, at the time, seemed to be the seat of sciences. So, taking advantage of the short-lived peace between Britain and Napoleon’s France, Manning traveled to Paris, where he reveled in the intellectual and social brilliance of French society. He met Chateaubriand, but no one who could teach him Chinese. Finally, he convinced the East India Company to send him to Guangzhou.

The China of Manning’s day was deliberately closed to foreign inquiry. It was forbidden for Chinese to teach their language to the few foreigners crowded in Whampoa, near Guangzhou. Voyages to the interior were forbidden. China’s unwillingness to open up was based on sound policy. The Jiaqing Emperor knew just how Britain’s trading ports in India had transformed into colonial conquests. Manning sympathized with the Chinese, as he had a radical streak, favorable to the American and French Revolutions, and critical of Britain’s exploitation of India. But this same radical streak made him constitutionally impatient with the even more protocol-minded Chinese. He kept importuning the mandarins for special permission to go to Beijing, but never succeeded.

Europeans were in the process of reevaluating China. Previous generations, imbued with the ideas of the Enlightenment, saw China as an ideal state ruled by a philosopher king. Manning’s enthusiasm for China reflected the temperament of the Romantics, who appreciated foreign cultures as all equally valid expressions of our essential humanity. Yet Manning’s increasingly utilitarian contemporaries saw Asian civilizations as obstacles to progress. The important people around him could only disapprove of his approach to studying China, which included growing an unfashionable beard and dressing in robes.

Any success Manning achieved reflected his charm, his academic accomplishments, and his great intelligence. Manning counted in his circle of friends Charles Lamb, George Staunton, Stanford Raffles, and Alexander Hamilton (the Sanskritist). He is the only person to have met both the Dalai Lama and Napoleon. He was eventually named an interpreter for the Amherst Embassy to Beijing, in 1816.

Yet Manning’s actual engagement with China, despite his excellent intellectual credentials, proved to be a bit of a damp squib. A casual friendship in Penang, a troubled relationship with a Chinese Catholic, invitations to the banquets of Puankhequa, the famous comprador, even being chased by the infamous woman pirate Shi Yang, none of these experiences seemed to have matured Manning’s thoughts about China enough to inspire him to produce a magnum opus.

In fact in his lifetime, he published very little. His youthful passion and ambition seem to have been consumed by the effort of penetrating forbidding China. After the failure of the Amherst Embassy, which left Beijing on the day of its arrival, his shipwreck off of Borneo, and a lengthy return to England via Saint Helena (where he met Napoleon), he avoided the limelight, refused a position with the newly formed Royal Asiatic Society, and seemed content merely to dine out with affable friends. It was an astonishing anticlimax to an adventurous life.

As his own illustrious circle of friends died out, Manning’s accomplishments were forgotten. Only in 2015 did the Royal Asiatic Society acquire Manning’s papers, enabling the society’s librarian, Edward Weech, to write this first, full biography. Readers will find a genial mix of erudition on Weech’s part, who is at home in the Anglican parishes of Norfolk, the salons of Paris, and the trading houses of Penang and Whampoa. Jane Austen or Anthony Trollope could not have invented a more colorful personage, whose story is engagingly retold here.

This is a review of “Chinese Dreams in Romantic England: the Life and Times of Thomas Manning” by Edward Weech (Manchester University Press, November, 2022). It was originally published by the Asian Review of Books. It has been republished here with permission. The author, David Chaffetz, is the author of “Three Asian Divas: Women, Art and Culture in Shiraz, Delhi and Yangzhou” (Abbreviated Press, November 2019). His next book, “Horse Power,” will be published by W. W. Norton in 2023.

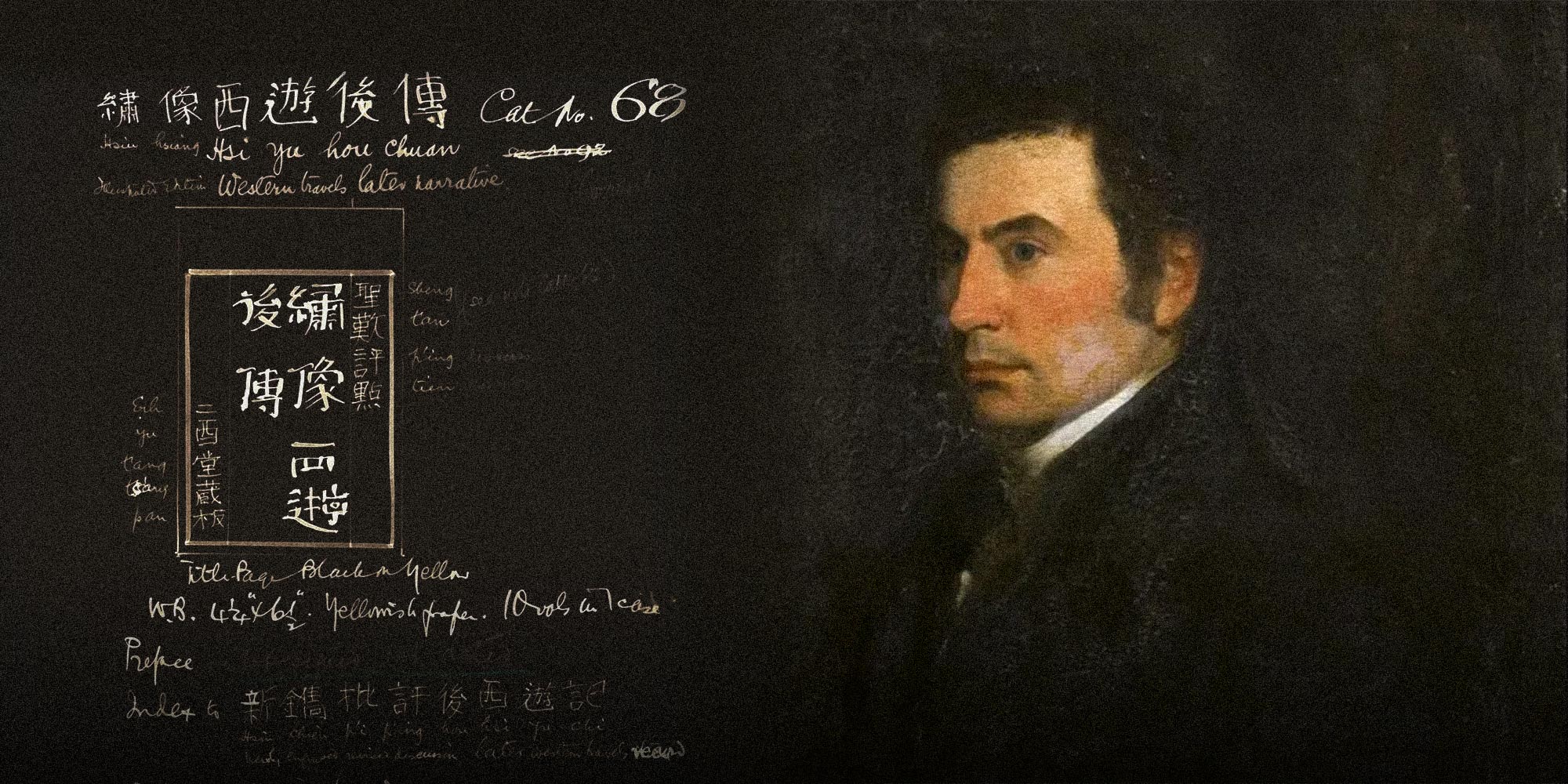

(Header image: A portrait of Thomas Manning. From Royal Asiatic Society, reedited by Sixth Tone)