A Bunny Hop Through Centuries of Chinese Art

Sandwiched between two powerful beasts — the tiger who rules over the mountain forests and the dragon who commands the forces of nature — the rabbit, this year’s zodiac animal, is more playful than intimidating.

But don’t let the floppy ears fool you: What rabbits lack in brute force, they more than make up for in wits, agility, and elegance — a combination that has won over generations of artists, poets, and writers and made them a fixture of Chinese culture for thousands of years.

China’s earliest known rabbit-centric artwork dates to the Neolithic period (7000-1700 B.C.). At the Lingjiatan site in what is now the eastern Chinese province of Anhui, archaeologists unearthed a 5,000-year-old ornamental rabbit made from jade. The rabbit’s ears are tucked behind its raised head and lie flat against its back, while its elongated body gives the impression that it is in full sprint. Along the rabbit’s lower body are four holes, reminiscent of the backs of combs from the nearby Liangzhu culture, indicating that the rabbit was perhaps meant to be joined with another ornament.

Another famous jade rabbit was uncovered in the tomb of the queen and general Fu Hao, who lived approximately 3,200 years ago. The ornament is essentially flat with exaggeratedly large eyes that recall one of the poetic names for a rabbit in classical Chinese: ming shi, or “sharp-sighted being.” A hole in the rabbit’s front paw allows the item to be worn as a pendant.

A very different type of jade rabbit was excavated from the Zhangjiapo site in what is today the northwestern Chinese city of Xi’an. Dating back to the Western Zhou dynasty (1045-771 B.C.), it has a rather unusual form: Its limbs are bent into a crouching position and sports two mushroom-like horns in addition to its ears — perhaps patterned on a fantastical beast from that era.

Over the ensuing 2,000 years, rabbits continued to flit about Chinese art. For example, during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), clay sculptures of a deity known as “Lord Rabbit” were extremely common fixtures in northern Chinese households. A rabbit with a glossy ganoderma in its mouth has long symbolized longevity and good fortune, and it was a common motif for jade ornaments during the Ming and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties.

Rabbits weren’t only featured in folk art; they were prized by Chinese literati for centuries, with writers and painters acknowledging both an affinity for, and a deep debt of gratitude to, the furry creature. That’s because one of the so-called Four Treasures of the Study, the inkbrush, was often made from rabbit hair. It is no exaggeration to say that, for millennia, rabbit hairs were pivotal to Chinese literary expression and history.

Ancient Chinese generally believed that brushes made from the hair of rabbits from the state of Zhongshan, near what is today the northern Chinese city of Shijiazhuang, were of the highest quality. As Cai Yong, a famous minster, man of letters, and calligrapher during the Eastern Han dynasty (A.D. 25-220), once wrote in an essay entitled “On Brushes”: “If a calligrapher writes under duress, not even a superior brush made from Zhongshan rabbit hair will allow him to produce a work of value.” The Tang dynasty (618-907) calligrapher Huai Su went through so many rabbit-hair brushes that the great poet Li Bai supposedly joked he had single-handedly driven the Zhongshan rabbit to the brink of extinction.

The fondness of Song dynasty (960-1279) literati for rabbit-hair brushes is responsible for the namesake of another unique item popular at the time: tuhao zhan, or “rabbit-hair cups.” A kind of delicate teacup, they belonged to a category of Song dynasty ceramics known as jian ware. Their name was inspired by their distinctive black glaze, which was characterized by fine lines resembling rabbit hairs.

The popularity of tuhao zhan was closely linked to the Song court’s love of tea. To prepare the drink, Song elites would first crush teacakes into a fine powder. Then, they’d steep the tea in freshly boiled water and whisk until a layer of white froth formed on the surface. This froth, as well as the stains left at the bottom of the cup, were important criteria when comparing different teas.

Black teacups were a natural choice for tea appraisals as they accentuated the beauty of this snow-white froth. But a simple black glaze was too bland for the court’s refined palates. Through experimentation, Song ceramists developed an ingenious method of firing the cups to produce intricate lines like fine rabbit hairs that radiated outward from the bottom. When fired this way, the bubbles that formed between the layers of glaze caused the iron inside the clay to rose to the surface. Once the temperature exceeded 1,300 degrees Celsius, the iron ran down the glaze, producing streaks, which cooled into hematite crystals resembling shiny animal hairs.

When filled with the delicate white froth of tea, tuhao zhan, were said to resemble black rabbits peeking through the snow, adding poetry to a seemingly banal activity like drinking tea.

It would be remiss to speak of the Chinese literati’s affection for rabbits without also mentioning their connection to the moon. Ancient astronomers believed the shadows on the surface of the moon resembled a rabbit, which gave rise to the simple yet charming legend of the Jade Rabbit, a deity that lived in a palace on the moon and spent its days grinding herbs into a medicine that could grant immortality.

According to the legend, the Jade Rabbit was the pet of Chang’e, the Moon Goddess, and they kept one another company in their cold and otherwise lonely days in the palace. China’s literary and artistic greats could hardly resist putting their own spin on such beautiful subject matter. The two most famous Chinese poets, Li Bai and Du Fu, both wrote poems retelling the Jade Rabbit legend.

But one of my favorite poetic depictions of a rabbit comes from the Song dynasty (1960-1279) writer Su Shi: “Round, yet not round / A crescent, yet not a crescent / Nestled in the middle is the Jade Rabbit.” The poem — most likely play on a special type of teacake which was embossed with the image of a rabbit — calls to mind an image of Su at work, sipping tea from a rabbit-hair cup and lifting his head to admire the moon. Struck by inspiration, he grabs his brush, the bristles made from Zhongshan rabbit fur, and excitedly scribbles down a poem as the subtle aroma of tea and the excitement of creation linger in the air.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

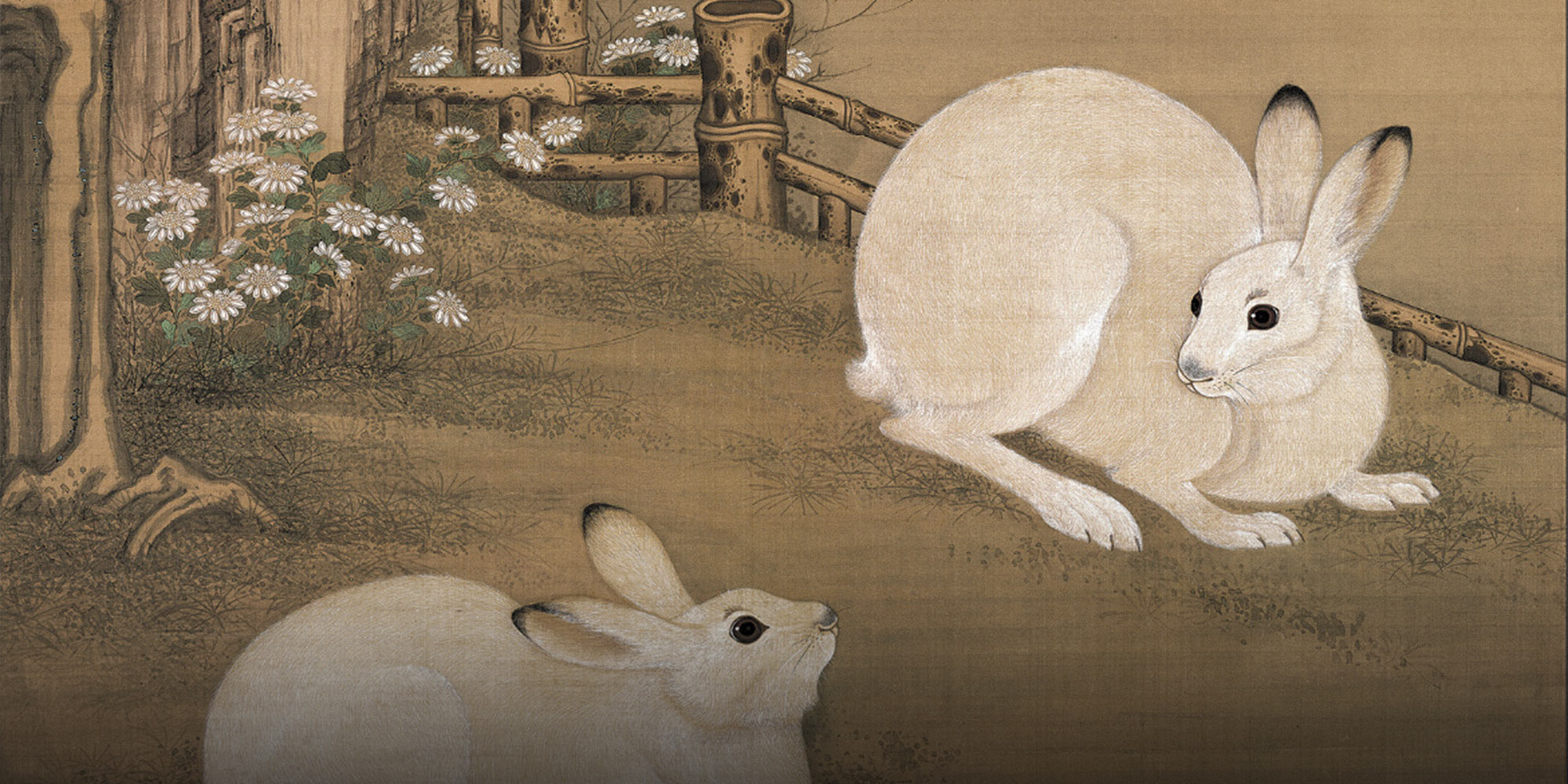

(Header image: Details of Twin Rabbits Under a Parasol Tree” by Leng Mei. From @天津博物馆 on Weibo)