The Forgotten History of Hong Kong’s Tigers

On a summer evening in 1905, three peanut farmers were sleeping overnight in the mountains of southern China to gather the harvest. But in a terrifying turn of events, they woke to find a 200-pound beast standing over them — a ferocious tiger.

Quick to react, the women grabbed their spears and rushed forward in a screaming frenzy. Nearby villagers heard the commotion and ran to the scene to help take down the feline, emerging victorious after a fierce struggle. They sold the meat to a market in Beihei.

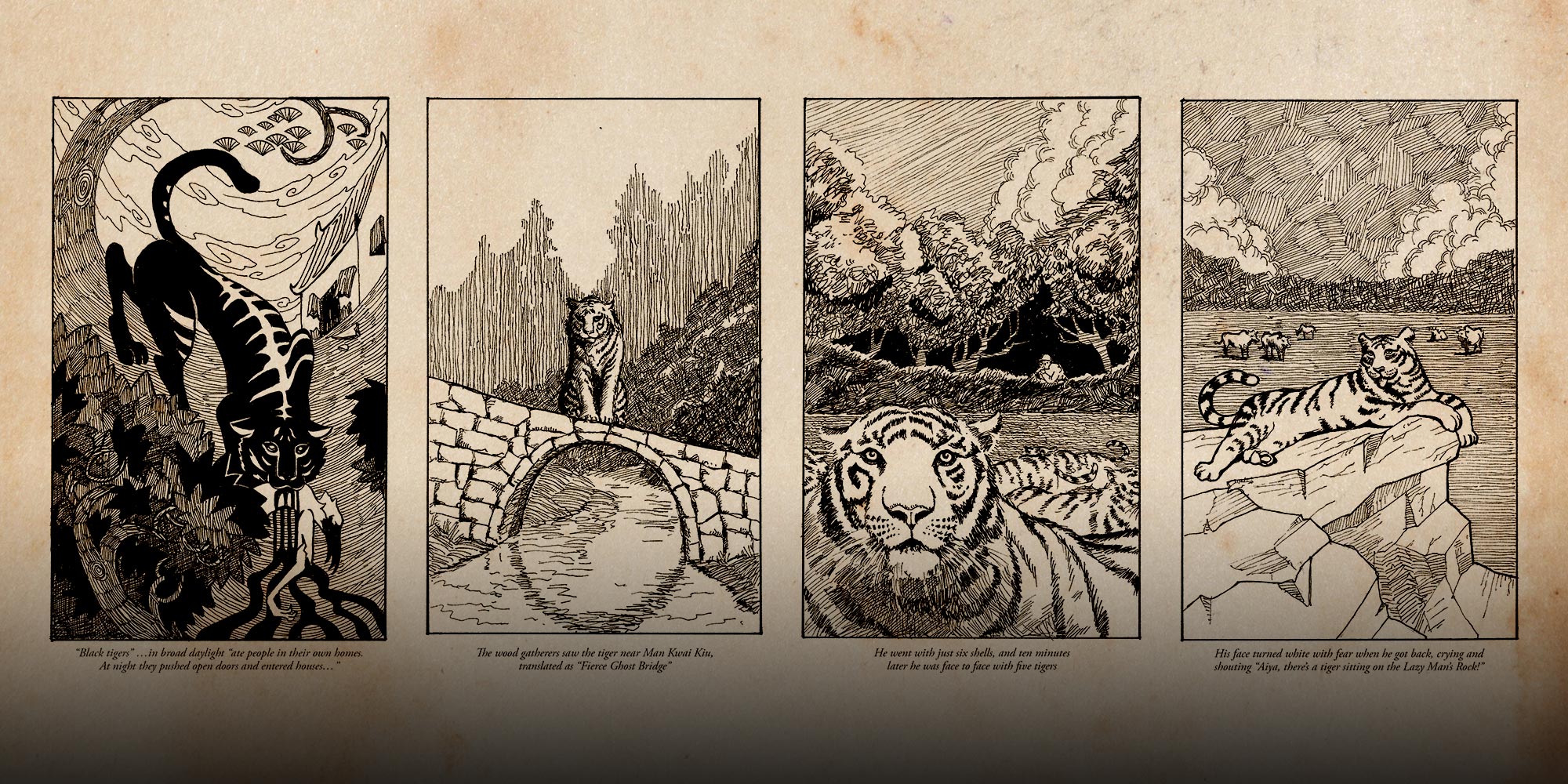

The anecdote is one of many that John Saeki unearthed while researching “The Last Tigers of Hong Kong” — a new book that argues big cats were once far more common in the city than previously assumed.

Tigers in Hong Kong? To people living amid the city’s forest of skyscrapers today, the idea seems far-fetched. There are surprisingly few records of tiger attacks recorded in previous histories of the island.

Until he started working on the book, Saeki had only heard of two famous incidents: the tiger that killed two Hong Kong policemen in 1915, and the dead tiger spotted outside a concentration camp in Stanley during the Second World War.

But when Saeki started digging, he began finding accounts of tiger sightings everywhere: in newspaper archives, in the work of British botanist Geoffrey Herklots, and even in local villages, where many seniors shared tales of livestock mauled by tigers.

In rural Hong Kong, tigers were a menace right up to the 1960s, according to Saeki. There are even reports of tigers swimming out to several outlying islands, including Lamma and Lantau.

These stories, however, often weren’t believed at the time. There was widespread snobbery toward villagers in the Hong Kong countryside — especially from the city’s colonial elite, but also from local city dwellers.

Reports of tiger attacks in the villages were usually dismissed as tall tales or exaggerations, Saeki says. The fact that tigers are such reclusive animals didn’t help, as it was difficult to verify these accounts.

“The reports the papers picked up on were often just fleeting glimpses or of prey that had been attacked,” he tells Sixth Tone. “On top of that, you get the sense that tigers just weren’t expected in the rather unglamorous scrubland of Hong Kong’s landscape.”

Crouching tigers

Yet some incidents were impossible to deny. In 1915, police officer Ernest Goucher and constable Ruttan Singh were investigating the death of a villager in Sheung Shui. The case had been reported as a tiger killing, but local media scoffed that reports of a tiger running loose likely reflected “the Chinese propensity for exaggeration.”

The tiger, however, was very real. It attacked and killed both policemen, before their colleagues managed to shoot the animal dead. The tiger was later skinned and stuffed, and its head can still be seen in Hong Kong’s Police Museum today.

Another famous case was the Stanley tiger killing — the last known slaughtering of a south China tiger in Hong Kong. In May 1942, rumors began to spread among the inmates at one of the city’s concentration camps that a tiger had been spotted in the area.

At the time, most internees considered the idea “preposterous,” according to Geoffrey Emerson, author of the book “Hong Kong Internment 1942-1945: Life in the Japanese Civilian Camp at Stanley.” Then, one morning, the camp woke up to find the body of a male tiger weighing over 200 pounds lying at their doorstep.

The beast was skinned by a former butcher named Bertram Walter Bradbury, and then stuffed to be put on public display. Its meat was served to officials at the Hong Kong Race Club, with the local press reporting that it was “as tender and delicious as beef.”

Other sightings included the “leaping tiger,” which was seen jumping onto the road near the Deepwater Bay golf course. Then there was a “pig thief of Sai Kung,” a tiger that apparently had a penchant for live pork.

In 1916, passengers on the tram running up to the Peak were terrified by a roaring tiger. Another animal reportedly interrupted a ceremony at a temple in Kowloon, before disappearing again.

At Repulse Bay in 1925, two ladies claimed to have seen a tiger walking up and down the beach. The “Lee Garden tiger” was caught in a snare at Sha Tin in 1926, and is now displayed at Lee Hysan’s Lee Garden Amusement Park.

One local ship’s crew even adopted a tiger cub as a mascot — though sadly the tiger later died after falling down the captain’s hatch. The list goes on and on, and is neatly logged by year in Saeki’s book.

Decline and fall

But where were all these tigers coming from? According to Saeki, researchers have found that the south China tiger was mainly active in the southern provinces of Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan, and Guangdong. But as solitary animals that like to roam far and wide, they needed plenty of space. Hong Kong, with its rugged landscape and plentiful livestock, was an ideal stomping ground.

Measuring up to 2.6 meters in length and weighing up to 380 pounds, the south China tiger likely prowled Hong Kong’s countryside for centuries. Unusually for a tiger, the species also loves water, which is why the animals were often spotted even on small islands.

The tigers, however, had a tense relationship with communities in the region, where they were feared and revered in equal measure. This mixture of fear and desire would ultimately cause the south China tiger to be all but wiped out in the wild.

On the one hand, tigers were prized for their supposed health benefits. In traditional Chinese medicine, “every part of a tiger’s body has powerful medicinal properties and is not to be wasted,” says Chris Coggins, author of “The Tiger and the Pangolin: Nature, Culture, and Conservation in China.”

On the other hand, the beasts could be a real danger to humans. Coggins found records of at least 10,000 deaths caused by tigers in south China within the past 2,000 years. To protect themselves, villages would organize expeditions to kill problem tigers, or hire professional tiger hunters to do the job.

“Tigers were sometimes a great menace to villagers, particularly under conditions of environmental degradation in which predators lacked sufficient natural prey,” says Coggins.

The killings accelerated after Westerners arrived in the region. Saeki cites the example of Harry Caldwell, an American Methodist who brought Christianity and guns to southern China. In an effort to convert villagers into Christians, he would teach them how to kill tigers, describing his 22-caliber rifle as a “calling card from God.”

Then came Chairman Mao’s “anti-pest” campaigns, under which tigers were labeled a threat to the creation of a socialist countryside. People were encouraged to kill as many tigers as possible, with hunters reportedly offered a 30-yuan bounty per tiger pelt.

As Coggins describes in “The Tiger and the Pangolin,” work teams would pursue tigers into the mountains and kill them with guns and grenades during this period. By the 1960s, tigers had retreated to isolated highlands where it was more difficult to locate and kill them. As their numbers declined on the mainland, they inevitably began to disappear from Hong Kong, too.

For Coggins, there are similarities between the decline of the south China tigers during the early years of the People’s Republic and the extermination of passenger pigeons and bison by North American settlers in the late 19th century.

“This story is a great cautionary tale of how nationalism can be a vector for ecological destruction,” he says. “China was to catch up with Great Britain in industrial production within a matter of years, and anything standing in the way of agricultural production and rural livelihoods was targeted as an enemy of national progress.”

Today, the south China tiger is presumed to be extinct in the wild. In the early 1950s, there were reported to be over 4,000 tigers in southern China. In 1977, the species was classified as protected, and hunting them was banned. But by 1987, there were only around 30-40 tigers left, and since 1990 there has been little evidence to suggest any wild tigers are still alive.

Yet, in 2018, the first reported tiger sighting in Hong Kong since 1965 startled the city. A couple in their 30s said they had seen a tiger during a hike, and reported the incident to the police. They later needed treatment for shock.

The couple’s story was deemed to be almost certainly false. Authorities concluded that they probably saw a leopard cat, a much smaller predator. But, given the history, it’s hard not to wonder.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Illustrations from the book “The Last Tigers of Hong Kong,” reedited by Sixth Tone. Courtesy of John Saeki)