A Chinese Classic Gets a Lovecraftian Twist

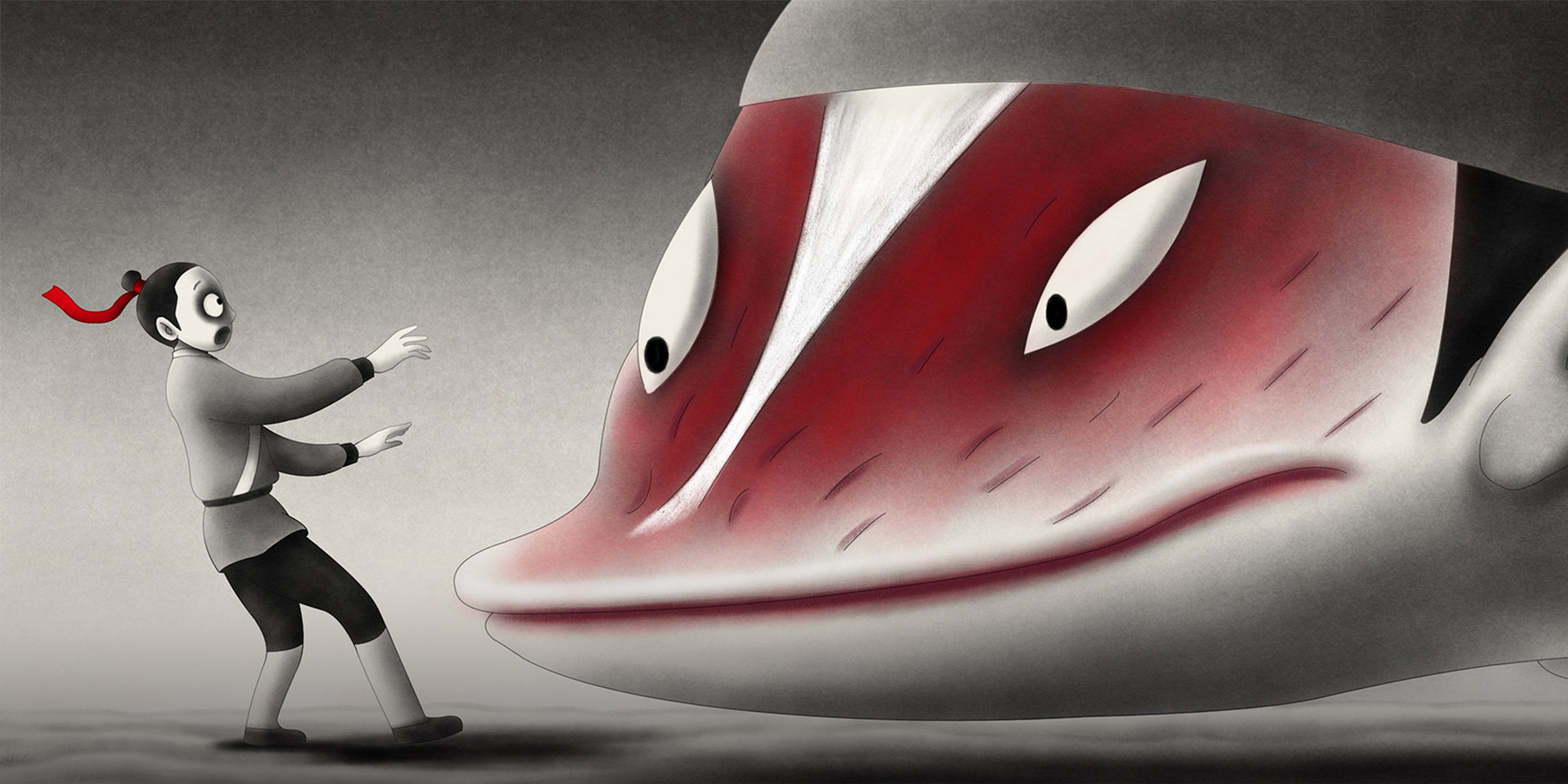

For the past two months, fans of Chinese animation have been transfixed by streaming platform Bilibili’s “Yao-Chinese Folktales.” The weekly anthology series, which has been watched 230 million times, according to the platform, was produced in cooperation with the legendary Shanghai Animation Film Studio in the vein of Netflix’s “Love, Death & Robots.” Each week, a different director puts a modern spin on a classic tale or theme, from the moon-bound Lord Rabbit to a lonely old man transported to a fantasy realm. But the standout episode, both artistically and in terms of its willingness to push the boundaries of the source material, was the series’ second: “Goose Mountain.”

Based on a classic tale of the strange, or zhiguai xiaoshuo, “Goose Mountain” tells the outlandish tale of an unnamed peddler who, on his way to deliver a cage full of geese, encounters a one-legged fox spirit. The spirit possesses and reroutes the peddler, ordering the man to carry him in the cage toward the episode’s eponymous mountain. When the pair stop to rest, the fox spirit produces his lover, a rabbit spirit, from his mouth. After the fox falls asleep, the rabbit spirit proceeds to regurgitate her own lover, a boar spirit, and swears the peddler to secrecy. Then the boar spirit spits out his secret lover, a goose spirit, with whom the protagonist shares a tender moment. Finally, as the fox begins to stir, the boar spirit swallows the goose spirit, the rabbit spirit swallows the boar spirit, and the fox spirit swallows the rabbit spirit.

According to the episode’s director, animator Hu Rui, the goal was to remain totally faithful to the zhiguai original — all he did was add a hint of romance between the peddler and the goose spirit. But this is misleading: Hu’s seemingly minor adjustment creates a sense of dramatic tension and mounting dread absent from the original.

To explain, we first have to take a look at the original. In his “A Brief History of Chinese Fiction,” the author Lu Xun identifies three versions of the story. The earliest, “The Parable of the King’s Pardon in the Palace,” is one of 21 stories compiled in the Indian Buddhist “Sutra of Old Miscellaneous Parables.” The second was included in the “Annal of Spirits and Ghosts” from the Eastern Jin dynasty (266-420).

Hu’s adaptation is largely based on the third version, “The Scholar From Yangxian,” which was included in the Six Dynasties (220-589) compendium “Continuation of the Records of Universal Harmony.” In this version, the protagonist, Xu Yan, carries a cage full of geese slung over his shoulder. A scholar — and not a fox spirit — hitches a ride on Xu’s back by shrinking down and slipping through the cracks of the cage. Later, he invites Xu to a banquet, where he produces utensils, crockery, dishes, and, last but not least, his own wife from his mouth. After the scholar goes to sleep, the enchanting wife produces a secret lover from her mouth and implores Xu to stay quiet. This man then regurgitates his own lover. When the trio realize that the scholar is about to wake up, the man swallows the woman, the wife swallows the man, and the scholar swallows his wife. The story ends with the scholar saying goodbye to Xu and presenting him with a bronze platter as a farewell gift.

The story structure of “The Scholar From Yangxian” pops up repeatedly in Chinese folktales. In his essay “On Narrative Form and Eastern Mise en Abîme,” Zhang Ning highlights the seemingly endless parade of tales in which smaller creatures are nested within larger ones, where large and small creatures consume one another, where a few creatures turn into many, and vice versa. “The Scholar from Yangxian” is story of worlds within worlds, of secrets containing secrets. The Chinese tale of the strange, Zhang ultimately argues, is a dreamscape.

The story does operate on a kind of dream logic. Although the only one completely in the know, Xu is a passive observer. He cannot meaningfully affect the action around him, and can only quietly watch the surreal sequence of events unfold. In the end, he awakens from his “dream,” and departs with his goose cage slung over his shoulder as everything seemingly returns to normal.

With that in mind, the curious alchemy of Hu’s adaptation comes into focus. “The Scholar from Yangxian” is a typical early zhiguai story: a casual, fairly suspenseless recounting of a bizarre anecdote. Throughout the narrative, Xu is never in any real danger. The scholar is impeccably polite for the entire duration of their encounter, and while Xu bears witness to a series of escalating betrayals, he is never implicated in them.

By contrast, “Goose Mountain” is a nightmare from start to finish. The protagonist is first stripped of his autonomy: Whereas Xu attends the scholar’s banquet of his own volition, the protagonist of “Goose Mountain” is possessed by the fox spirit and forced to go wherever he wants. Hu’s addition of a romance between the protagonist and the goose spirit only further ensnares the peddler in the spirits’ web. No longer is he an external witness to strange goings on — now, he, too, is complicit in the other characters’ deceit.

If “The Scholar From Yangxian” is like a set of nesting dolls, each opening to reveal another, even odder phenomenon, “Goose Mountain” exchanges curiosity for horror by including its protagonist — and by extension, the audience — among the playthings. We no longer enjoy the luxury of standing on the sidelines as this ouroboros devours itself; instead, by disturbing the cycle, we are lucky not to end up in the belly of the beast. It’s Chinese folklore by way of Lovecraft.

“Yao-Chinese Folktales” is an experiment in Chinese aesthetics, and its success highlights the possibilities inherent to empowering creators to support or subvert classic tropes. Not every episode is as gripping as “Goose Mountain,” but when it clicks, the show is proof that neither folklore nor animation have to be relegated to the kids’ section.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A still from “Yao-Chinese Folktales.” From @胡睿_Ray on Weibo)