What Makes a Good ‘Three-Body’ Adaptation?

The first attempt to bring Liu Cixin’s “The Three-Body Problem” to the big screen ended in complete failure.

In 2009, when Liu’s “Remembrance of Earth’s Past” series was still largely unknown outside of Chinese science fiction circles, the horror film director Zhang Panpan bought their film and television adaptation rights for the absurdly low sum of 100,000 yuan (then about $14,600). Five years later, as the series’ popularity grew, Zhang collaborated with the media company Yoozoo on a film version. The project never got anywhere near cinemas. Among fans, rumors spread that it was unwatchable.

In 2018, after Zhang sold the rights to Yoozoo for $18 million, the company tried again, this time by fast-tracking development on several proposed adaptations at once. The first of these, an animated version co-produced by YHKT Entertainment and streaming platform Bilibili, finally premiered in late 2022, followed quickly by a live-action adaptation from Tencent this January. An English-language adaptation is slated to hit Netflix later this year.

Much of the early press in the runup to the two shows’ release focused on YHKT’s animated adaptation. A well-respected studio known for hits like “Incarnation,” YHKT seemed ideally positioned to translate Liu’s ambitious worldbuilding into reality, while Tencent struggled to overcome a ham-fisted marketing campaign that seemed to suggest a fast-and-loose approach to the source material.

What a difference a few months makes. Almost immediately, fans turned on the animated version, sending its score on popular ratings site Douban plummeting to a lowly 3.9 out of 10; meanwhile, the live-action version has come from behind to almost completely displace its rival in the popular zeitgeist.

At the root of this reversal, ironically, is the live-action adaptation’s far better grasp of Liu’s original. YHKT opted to all but skip the entire first book in the series, opening with the climax of “The Three-Body Problem” before immediately segueing into its sequel, “The Dark Forest.” This decision may have been motivated by the difficulty of portraying Liu’s searing vision of the Cultural Revolution in the current media regulatory environment, but based on the scenes the show does include, it is just as likely that YHKT was worried the first book’s lack of action would bore viewers.

By contrast, the second book offers a Hollywood-ready heroic narrative, one which YHKT pairs with a hero straight out of a 1990s action flick: The show spends copious screentime establishing the protagonist, Luo Ji, as a bad boy, even adding scenes not in the book to reinforce his character’s personality: He drives a race car, flies a fighter jet, and hosts extravagant parties.

The animated version’s obsession with Hollywood sci-fi, even at the expense of Liu’s “golden-age” reference points, is also reflected in its art direction. The series’ futuristic cities are portrayed as cyberpunk wastelands, a choice at odds with the spirit of Liu’s work. As a fan of Arthur C. Clark and a writer deeply influenced by both traditional Chinese culture and socialism, Liu retains a strong faith in the future. This faith is absent from YHKT’s imitation-cyberpunk style.

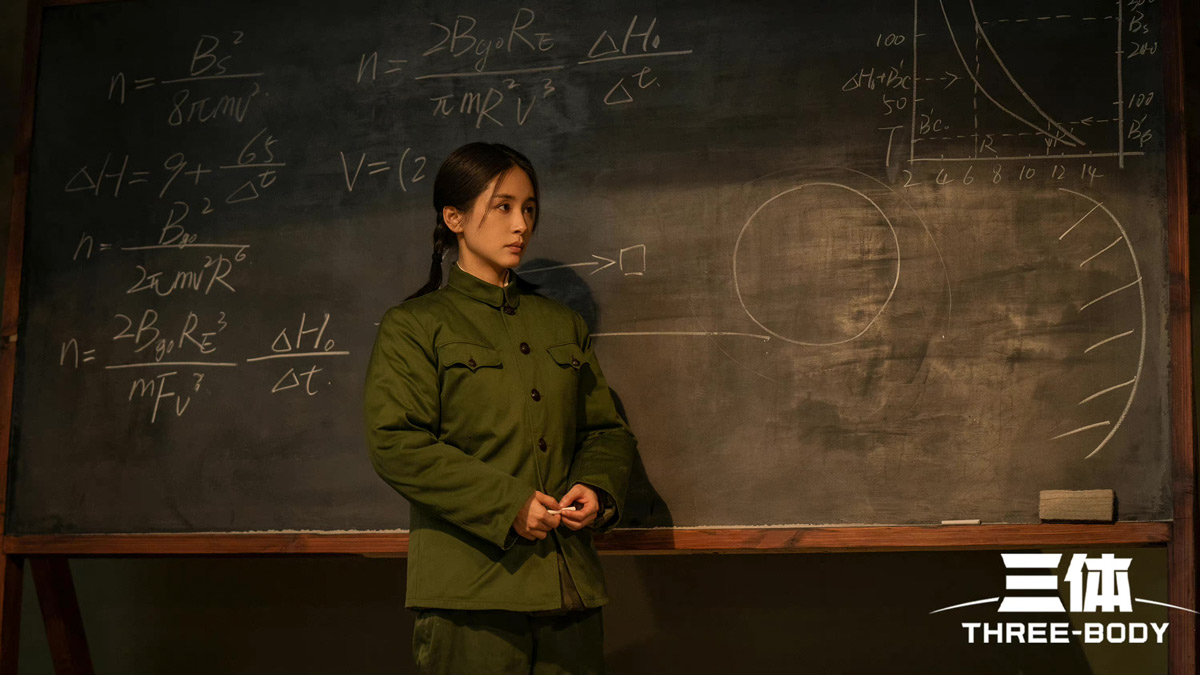

Contrast this with the live-action version, a high point of which was its adaptation of life in the Greater Khingan Mountain Range in the 1970s — a place imbued with revolutionary enthusiasm and regarded by many fans as the setting of the first book’s most exciting chapter.

Indeed, despite the early concerns, it’s not an exaggeration to say Tencent’s adaptation is the most loyal to its source material I’ve seen since CCTV adapted China’s “Four Great Classical Novels” in the 1980s and ’90s. Discerning viewers will find that many scenes and lines in the series are taken verbatim from the book.

This is not to say the Tencent version is the definitive adaptation of “The Three-Body Problem.” To begin with, although the show is popular, its success still pales in comparison to the attention given to the recent gangster drama “The Knockout.” And Chinese directors still struggle to balance faithfulness to the source material with the needs of on-screen action. For example, one dialogue-heavy riddle sequence has thrilled fans of the book for its fidelity to Liu’s vision; for an ordinary viewer, however, the scene’s barrage of new concepts is exhausting, and something the show could improve on in its second season.

In the meantime, the pressure is now on Netflix. Enthusiasm within China for the streaming platform’s adaptation has been low since news broke it would be helmed by David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, the pair responsible for the infamous finale of “Game of Thrones.” While it will likely benefit from high-quality special effects and a far larger international audience, many Chinese fans worry about the difficulty of globalizing a very Chinese story without losing its local flavor. They fret it’ll fall into either essentializing stereotypes about China or become a clichéd Hollywood narrative about saving the world.

Then again, the charm of Liu’s novel lies in the room it leaves for interpretation. A mix of Chinese history and golden-age futurism, local color and universal themes, it offers endless room for experimentation. The best adaptations should not just be loyal to the original work, they should offer us a mirror through which we can see ourselves.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Promotional images of Tencent (left) and YHTK's adaptations of “The Three-Body Problem.” From Douban)