Family Records: The Story of China’s Largest Genealogy Collection

Last fall, when the Shanghai Library opened a massive new branch in the city’s Pudong District, headlines tended to focus on two things: its size and architect Chris Hardie’s design, which included exhibition, performance, and event spaces in addition to the customary stacks.

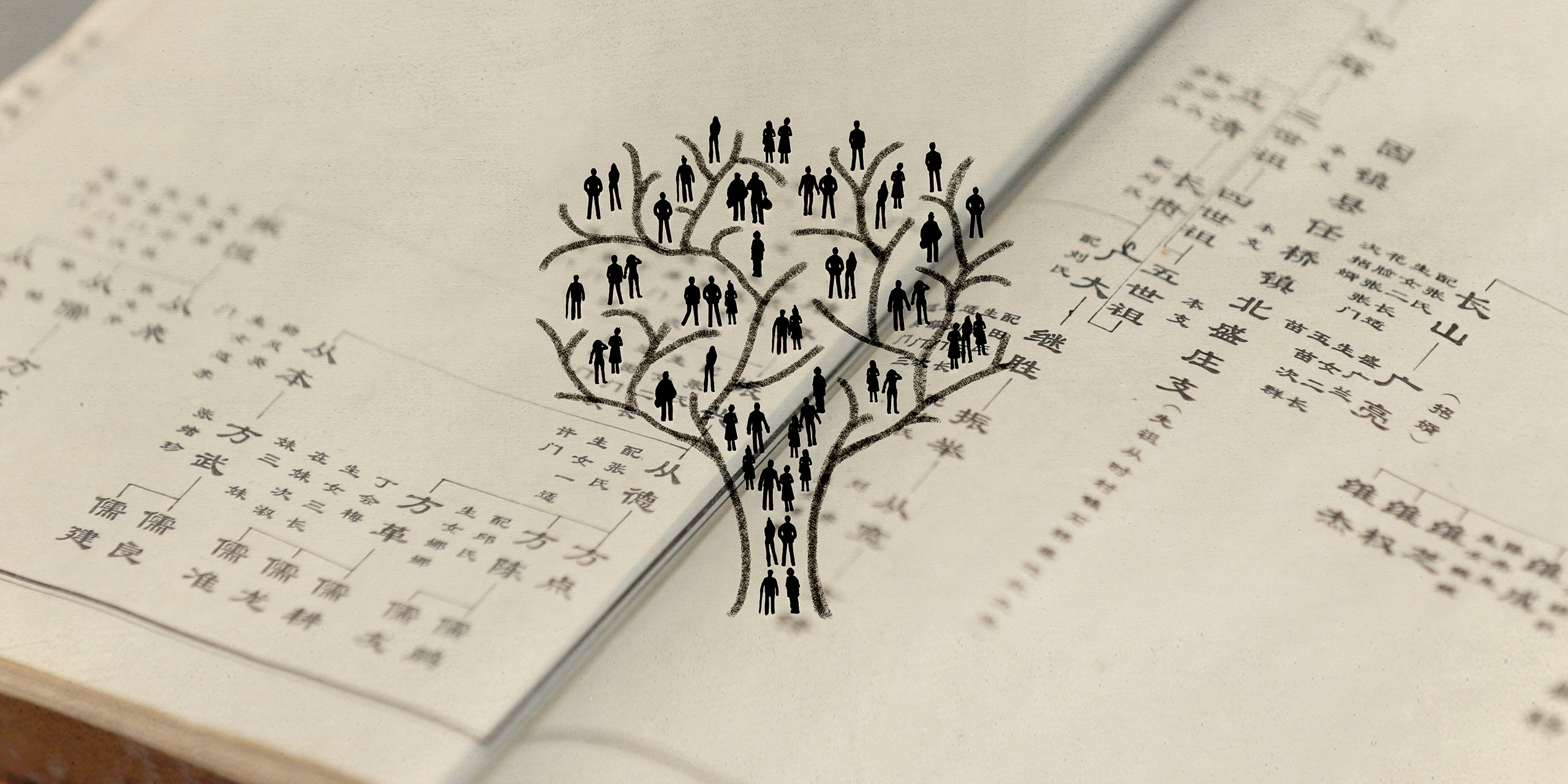

Somewhat lost in all this was the library’s collection, one of the driving reasons for the expansion in the first place. (Full disclosure: As an employee of the library, I am responsible for some of that collection.) In particular, the Shanghai Library is home to arguably the world’s top collection of Chinese genealogies, including more than 300,000 volumes of nearly 40,000 different genealogies, totaling 456 surnames.

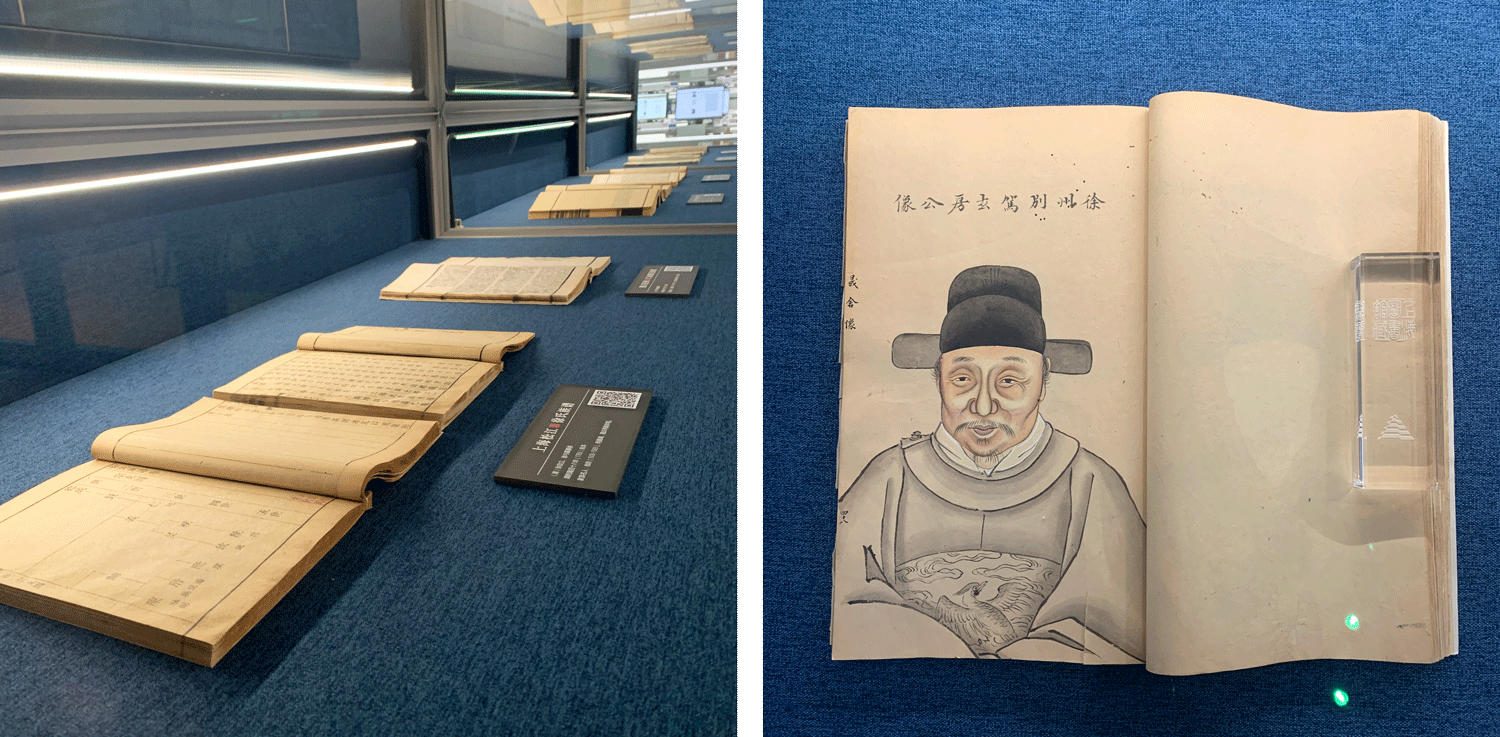

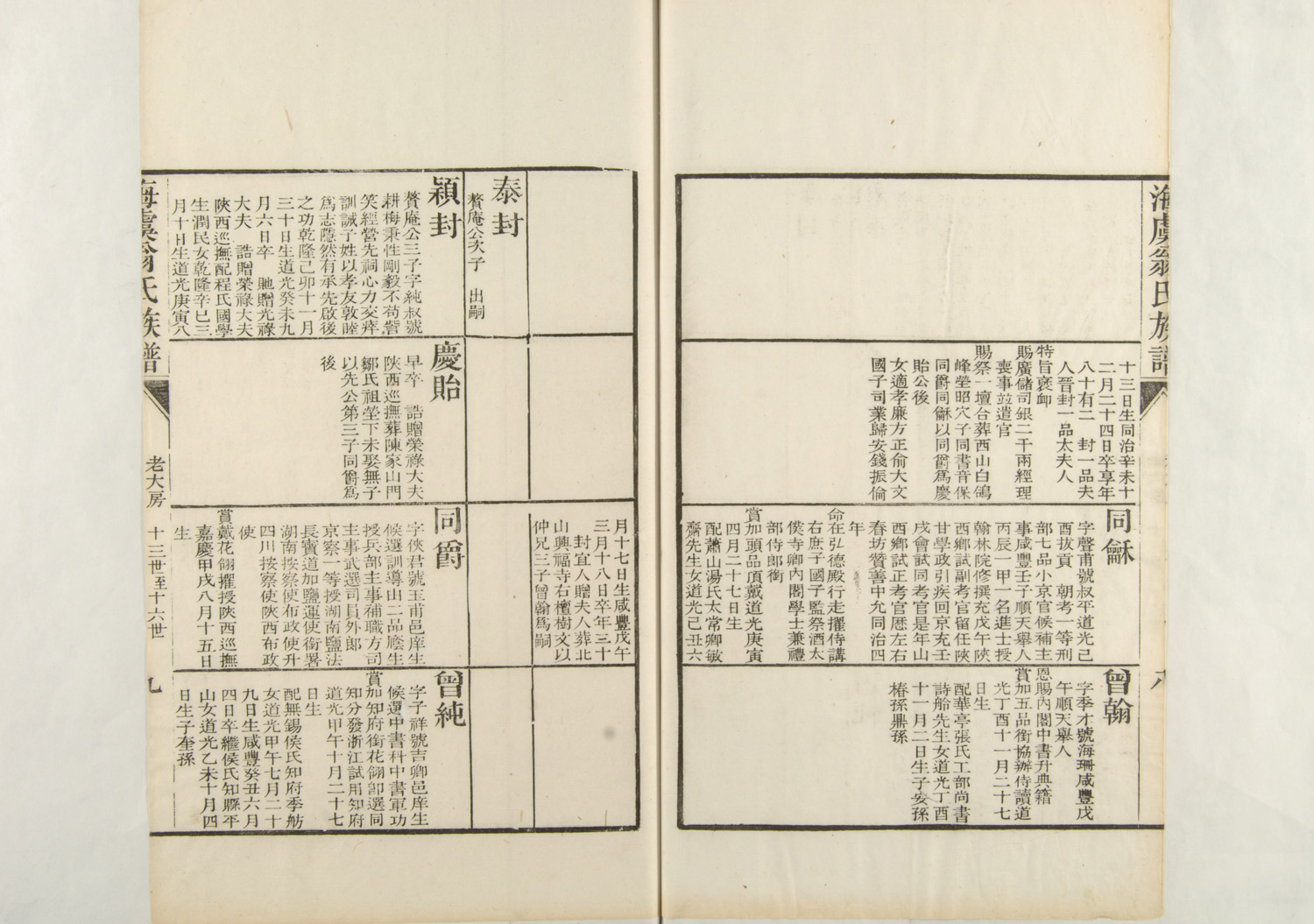

A genealogy is a historical document that records the lineage of a blood line descended from a single ancestor, the blood relationship between family members, and a family’s assets and customs. They can include depictions of famous family members from history, textual research on the origin of a family’s surname, clan rules and regulations, information on the construction of ancestral halls, even poems. Genealogies of famous families often contain archives of special records, including imperial edicts, orders, and letters given by emperors to officials in the family. (One thing they do not typically include are records pertaining to female members of the family.)

Particularly old genealogies will have dozens of prefaces from different periods, produced by members of different generations attempting to organize hundreds of years of history into something legible. Some scholars argue the practice dates to the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.), though it didn’t reach its peak until the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern dynasties period (roughly A.D. 220-581). In an era dominated by powerful clans, genealogies were a vital means of establishing family ties, blood relationships, marital alliances, even bureaucratic posts. At the time, officials were selected, not on merit, but on the basis of their family’s legacy, with various clans sorted into one of nine ranks.

From the Sui dynasty (581-618) on, the imperial examination system gradually replaced the original nine-rank system, and the power of noble clans declined. Beginning in the Song dynasty (960-1279), a new style of genealogy emerged: chronicles. A chronicle is essentially a profile of a single person or event. Mostly done by famous politicians and scholars for their predecessors or an especially brilliant contemporary, they’re a bit like a celebrity biography written by another celebrity, and they remained popular until the beginning of the Republic of China period (1912-1949).

Meanwhile, during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, the government sought to shore up faith in filial piety and the clan system as a bulwark against social upheaval. The Kangxi and Yongzheng emperors both called for the collection of genealogies, and local officials persuaded families to compile them. As the campaign took root, people began to believe that there was “no family without a genealogy.”

It may seem curious, given the long history of genealogies in China, that so many would wind up in Shanghai — not a city known for its connection to traditional culture. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the collection of genealogies largely paused. Except for 1950 and 1951, when a small number of genealogies compiled before 1949 were printed, the genealogical record went blank for more than two decades. Genealogies were labeled “feudal” accomplices to the patriarchal system, those who compiled them ran the risk of being accused of nostalgia for the old China, and many volumes were sent to pulp mills.

With thousands of years of history at stake, a Shanghai librarian named Gu Tinglong took a risk and organized a team to rescue as many genealogies as they could from being chemically pulped or thrown into landfills. Their work accounts for two-fifths of the Library’s current collection, with the rest coming from acquisitions made since the 1960s.

The historical value of genealogies can vary wildly by era. For example, genealogies from the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern dynasties period are a rich source of material for scholars, containing details on the era’s families, politics, marriages, even ethnic relations. But their trustworthiness is not absolute: Because China has a long tradition of “venerating the elderly, speaking well of the well-known,” the lineages and deeds of members are often exaggerated.

More recently, Chinese scholars have begun to emphasize a more international approach to the study of genealogies. This led to an unlikely partnership with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, more commonly known as the Mormons. Because Mormon doctrinal teachings attach great importance to the family, the Mormons have amassed a large amount of genealogical data. The International Genealogical Index, a global nonprofit genealogy research organization founded by the church in 1894, has collaborated with over 10,000 archives, libraries, and other institutions in over 150 countries. That includes the Shanghai Library, which worked with the IGI to compile the Comprehensive Catalogue of Chinese Genealogies, opening its archive to researchers around the world.

Translator: Matt Turner; editor: Wu Haiyun.

(Header image: A genealogy of a family surnamed Sheng, from Bengbu, Anhui province, 2014. Li Bin/IC; Center: Pepifoto/VCG)