The Minoritization of a Transnational Superstar

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” was the biggest winner at the Oscars this year, sweeping the awards for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Film Editing, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Supporting Actress. Featuring a majority Asian cast including Michelle Yeoh, Ke Huy Quan, and Stephanie Hsu, the film explores the intergenerational conflicts and reconciliations of a Chinese American family across multiple universes.

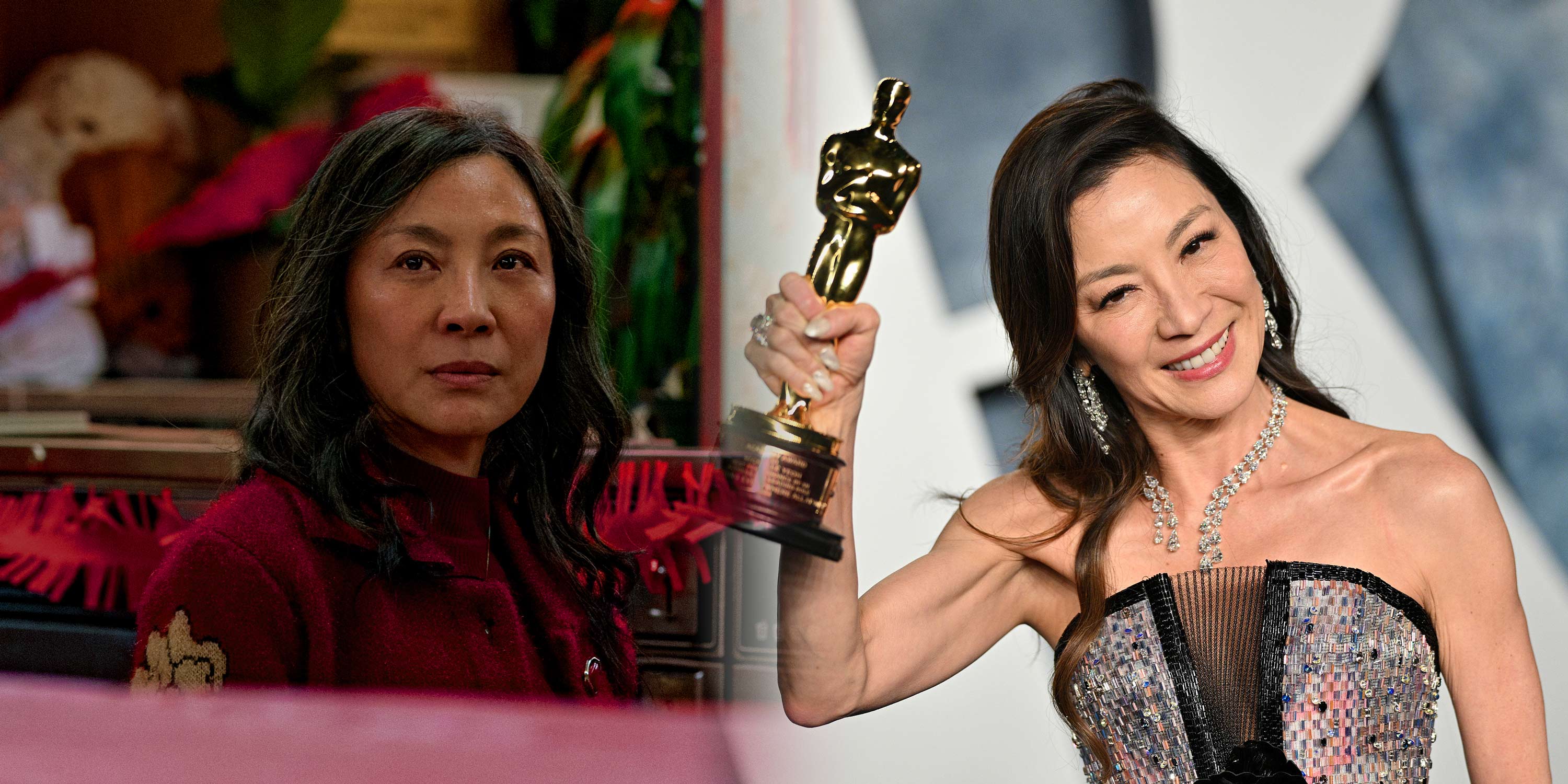

Arguably the most important win of the night belonged to Michelle Yeoh, who became the first Asian woman to win a Best Actress Oscar for her role as a multiverse-jumping immigrant mother. It’s a major achievement, and Yeoh’s acceptance speech reflected the moment’s historic import: “For all the little boys and girls who look like me watching tonight, this is a beacon of hope and possibilities. This is proof that … dreams do come true.”

While Yeoh’s award is undeniably a huge inspiration to Asian actors everywhere, the reference to boys and girls “who look like me,” when situated in the contemporary American context, reminds people of the persistent racial myth that people of East Asian descent all look alike. Audiences in Asia might have a difficult time understanding the expression without at least some knowledge about the racial dynamics in the United States, since to them, every “Asian” around them looks different.

Although later in her speech, Yeoh briefly mentions her family in Malaysia and her colleagues in Hong Kong, where she started her career, one cannot help but sense that she’s downplaying her transnational background in favor of catering to local minority politics, reducing her journey from kung fu star in Hong Kong to first Asian Best Actress in Oscars’ history to a traditional minority success story narrative. For all the talk of Hollywood’s growing diversity, its U.S.-centric approach to Asian characters in film and Asian film workers is unlikely to be challenged by her win.

The adjective “Asian” is problematic in this context, as it reduces the very diverse national backgrounds and career trajectories of different people into a single ethnic label. In the U.S., different media outlets apply the term to American-born actors like Anna May Wong or Lucy Liu, first-generation immigrants like John Cho or Steven Yeun, and Asia-based actors who make brief forays into Hollywood like Zhang Ziyi or Gong Li. Towering over them all are a handful of global stars who transcend any local market, such as Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, but even they are subject to the “Asian” label in American media.

With her academy award, Michelle Yeoh would seem to have completed her transition from an Asia-based actress with occasional appearances in Hollywood blockbusters to global superstar status. However, as her speech suggests, the tension between her background and the representational politics of ethnic minorities in the U.S. has hardly disappeared.

Yeoh is certainly aware of the minoritizing force imposed on Asian film workers. She has had plenty of first-hand experience in this regard since she started collaborating with American directors and actors in the late 1990s. In her acceptance speech at the Golden Globes earlier this year, for example, she remarked: “I remember when I first came to Hollywood. It was a dream come true, until I got here. Because look at this face. I came here and was told, ‘You’re a minority,’ and I’m like, no, that’s not possible. And then someone said to me, ‘You speak English.’ I mean, forget about them not knowing Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Asia, India. And then I said, ‘Yeah, the flight here was about 13 hours long, so I learned.’”

Although she relayed these first impressions and embarrassing encounters in an ironic tone, Yeoh’s words nevertheless offered a nuanced critique of Hollywood’s U.S.-centric approach to “multiculturalism.” By assuming that Asians are “a minority” and do not “speak English,” this racialized logic automatically treats all Asians as minority immigrants while perpetuating public ignorance about the colonial history of Asia.

Yet, despite their awareness of the inner workings of the American cultural industry and society, Asian actors may still feel compelled to fall back on U.S.-friendly discourses like Yeoh’s “look like me” remark at bigger events like the Oscars. They do this to mobilize the legitimating power of racial representation, thereby affirming the value of their achievements beyond the liberal celebration of individual success. As Yeoh’s Vietnam-born co-star Ke Huy Quan declared in his own Oscar speech, “This is the American Dream!”

There is another important reason why Yeoh may have wanted to tone down her transnational background, and it has to do with the character she plays in “Everything Everywhere All at Once.” Her character, Evelyn Wang, is a middle-aged Chinese immigrant mother who runs a laundromat in an unspecified California city. She is struggling to pay her tax bills and faces multiple crises unfolding in her family, including her daughter’s lesbian relationship, her demanding father’s health issues, and her deteriorating marriage.

Yeoh’s own life story could not be more different from Evelyn’s. She was born into a rich Chinese family in Malaysia and became a household name in the Chinese-speaking world after she moved to Hong Kong to act in films in the 1980s. In contrast with Evelyn, Yeoh is both economically privileged at birth and highly successful in societies where Chinese is the majority ethnic group. Even as her Academy Award acknowledges her acting skills for portraying Evelyn, Yeoh must also try her best to fit into a minority role to better legitimize her win. In particular, the class and racial privileges underpinning her transnational background must be “yellow-washed” to appease possible complaints from the Asian American community that a foreign superstar has taken precious opportunities from U.S.-born or -based actors.

Apart from the domestic context in the U.S., the current state of relations between China and America is also a factor behind the sweeping success of “Everything Everywhere All at Once.” From the trade war with China to the proliferation of Sinophobic and racist attacks against Asians during the COVID-19 pandemic, China-America relations — and the position of ethnic Chinese in American society — have deteriorated noticeably in recent years. At a time when talk of a “New Cold War” is not uncommon, the mainstream progressive forces in American society, such as the cultural industry, have sought to show that America is still a tolerant and diverse society while insulating themselves from critics like those behind the #OscarsSoWhite campaign. Indeed, new inclusion policies due to take effect next year include clauses that seek to boost the hiring of actors and crew members from “underrepresented groups.”

To be clear, it is not at all my intention to deny that “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is a creative movie. Viewed in the genealogy of Asian American filmmaking, it is indeed groundbreaking in many respects. It features an ordinary middle-aged Asian mother as its heroine, juxtaposes stereotypical images of Chinese culture with recognizable references to Chinese cinema, and mixes different popular genres with kitsch aesthetics to maintain a self-parodying tone. Never has there been an Asian American film that manages to play with all these elements and yet still resonate with different audiences beyond the Asian American community.

As such, to simply dismiss its success as a symptom of the rise of American political correctness is unfair. However, by paying more attention to what happens after its initial success, we can see the changing terms and limits of Asian representation globally. It is in the public speeches and performances of actors like Yeoh and Quan that the complex cultural politics transnational people of Asian background have to navigate in their work become visible. Such critical observations can help us reflect more on the persistent U.S.-centrism of Hollywood even as its policies and discourses on issues of race and diversity continue to shift.

Editor: Cai Yineng.

(Header image: Left: A still from “Everything Everywhere All at Once.” From Douban; Right: Michelle Yeoh attends the 2023 Vanity Fair Oscars Party in Beverly Hills, California, U.S., March 12, 2023. Lionel Hahn/VCG)