Shanghai Bus Ridership Is Down. Does Anyone Care?

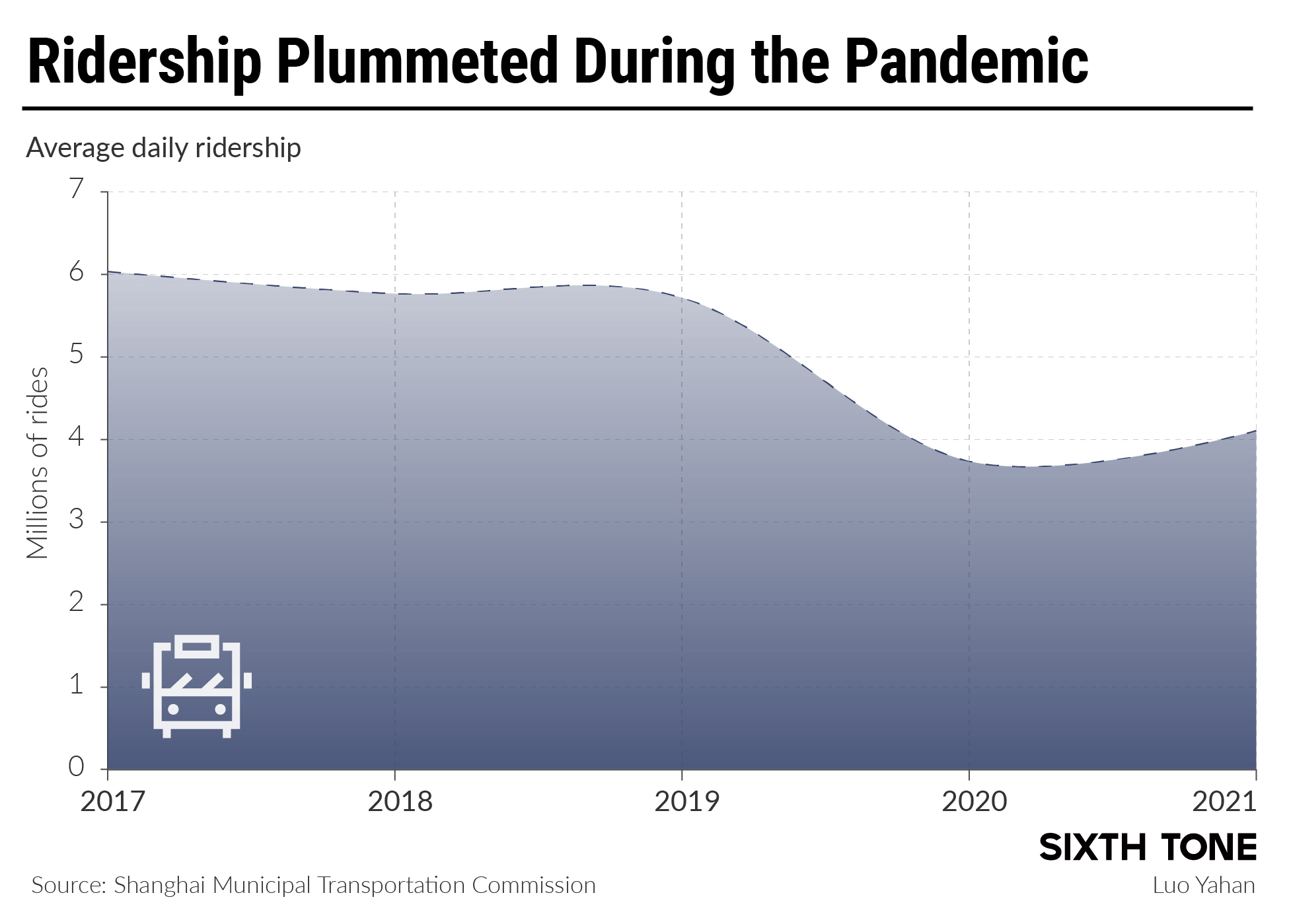

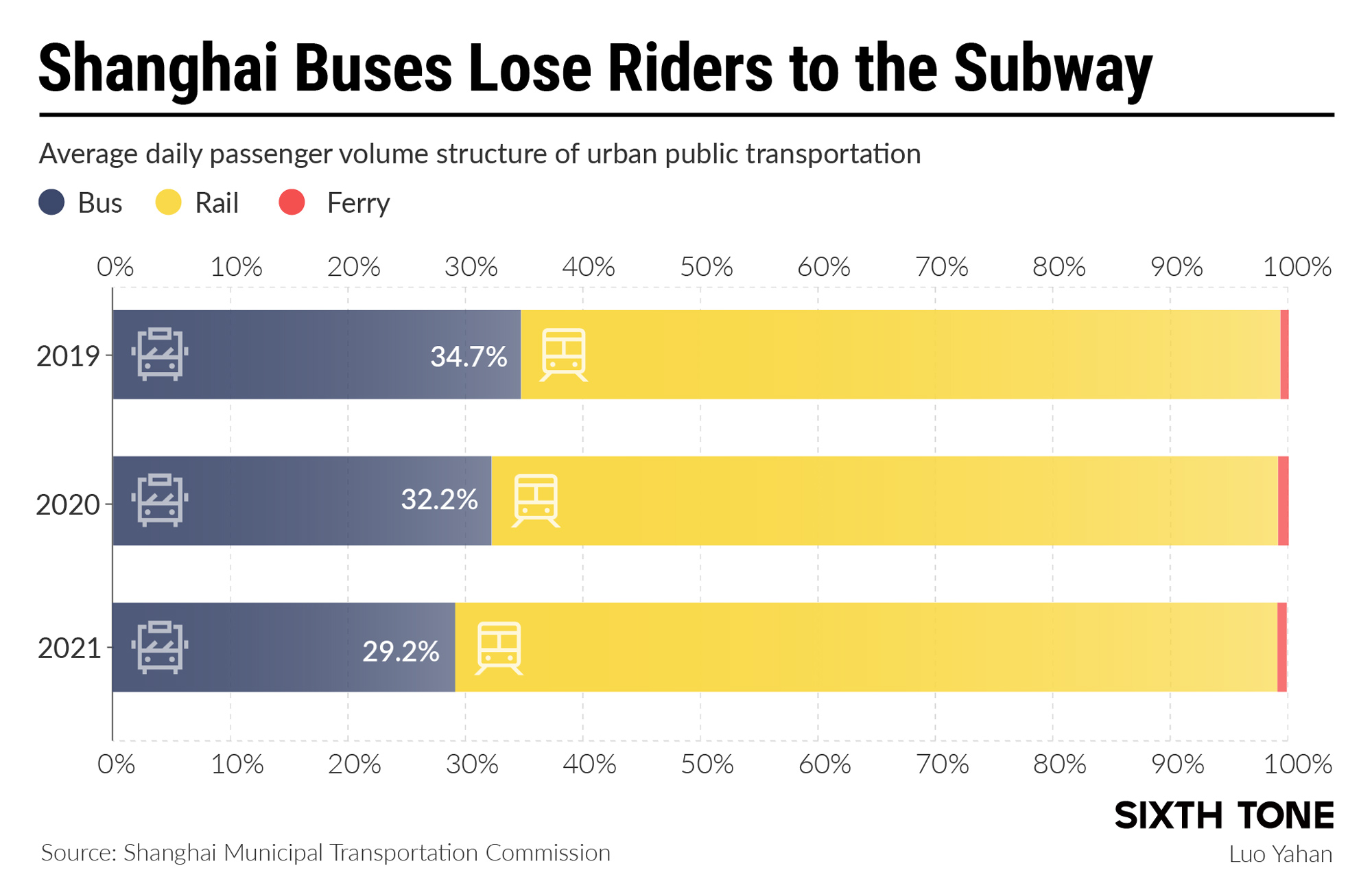

Once one of the city’s calling cards, Shanghai’s bus system is a shell of its former self. Daily ridership dropped under 6 million in 2017 before falling off a cliff during the pandemic. A recent report from a city government-affiliated think tank found that passengers took 4.1 million trips per day in the city using above-ground public transport in 2021, down nearly 30% from pre-pandemic levels.

To understand what’s going on, it helps to start from the two major industry reforms of the past 20 years. In the early 2000s, Shanghai marketized its above-ground public transport system, introducing various new kinds of enterprise ownership models, such as privately run and joint-stock public transport companies. At first, the rise in efficiency that accompanied these reforms led to a boom in ridership, as buses became a much more attractive travel option. But a lack of government oversight soon devolved into chaos, as private firms illicitly subcontracted routes out to independent operators with no interest in following the rules of the road, much less the posted bus schedules.

Eventually, the situation led Shanghai to implement a second round of reform around the beginning of the last decade. Public transport was classified as a “public welfare industry with market-oriented operations,” with public welfare taking precedence over market imperatives. The private bus companies that had flourished during the 2000s were replaced by state-backed firms that would ensure the city’s directives were followed.

The primary source of income for these companies was government subsidies, which were meant to cover policy-related losses like subsidized tickets for elderly residents, late-night routes, or mandated investments in facilities and equipment like electric buses. Self-generated income like tickets was of secondary importance, meant only to help companies make up for any remaining budget shortfalls.

Although the reforms stabilized the bus network, the balance they promised between transit as a public service and marketization never materialized. Operating costs have skyrocketed thanks to rising labor costs, new-energy vehicle purchases, and the need to keep unprofitable routes in service, while popular opposition to fare hikes has ensured bus fares generally remain stuck at 2 yuan ($0.29) per trip — the same price they were 20-plus years ago. Government subsidies have also failed to keep pace: The subsidy for gasoline, for example, has not been increased since 2017.

The core model of bus companies as public service first and market entity second is unlikely to change anytime soon. Across-the-board fare hikes have been mooted for years, but there are few signs the city will approve them anytime soon, while cost-saving measures are almost entirely off the table.

With costs mounting and fares stuck in the early 2000s, you could be forgiven for thinking Shanghai’s bus companies are in crisis. But if the industry insiders I interviewed over the past year are any indication, there is little urgency for reform.

Take the climate, for example. While China’s ambitious carbon neutrality goals appear to offer a rare development opportunity to the above-ground public transportation sector, many of the enterprises I studied lacked the motivation to actively calculate their emissions and pursue potential new subsidies. Rather, most preferred to passively comply with government rules, such as upgrading their fleets to new-energy vehicles.

The opportunities afforded by new digital technologies are likewise being missed. Companies have invested heavily in digital services, including new signs at bus stops and monitoring technology to track routes, but there is little appetite for using tech to reshape management processes, cut operating costs, or improve efficiency. As with electric buses, this approach increases capital costs while doing nothing to boost the bottom line.

A few bus enterprises have experimented with market-based initiatives like custom shuttle bus routes, but allocating resources to this new business has proven challenging. Demand for shuttles, like that for buses, is concentrated around peak travel hours and along main routes. As such, bus enterprises have struggled to operate both, instead prioritizing their traditional, if not necessarily more profitable, bus lines. After all, that’s the only way to guarantee they receive their full government subsidies.

The primary exception to this malaise is real estate development. In my research, I found that bus companies see the land development strategy of metro systems as a potential model and solution to their financial problems. For years, there have been restrictions on how land around many bus stations can be developed, but a new policy may allow the bus industry more latitude for integrating commercial and office development.

The most promising policy shift of the past few years arguably has nothing to do with buses at all. In 2021, Shanghai announced plans to build five cities in its suburbs, a move that, in theory, could create mini downtowns in what are today remote areas.

At present, bus coverage in these areas is woefully inadequate. Bus stops serve between 50% and 70% of the new cities, and public transport ridership is less than half that of downtown. If the plan works — and if bus companies move quickly to establish new local routes — buses could be ideally positioned to help suburban residents manage their new, shorter commutes to these emerging city centers.

Bus companies across China have been hard hit over the past few years. Shanghai may have the resources to ride out the downturn, but the contradictions between busing as a public service and the expectation that bus firms will be only partially reliant on government subsidies to survive will have to be addressed sooner or later.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A bus with a vintage-inspired design in downtown Shanghai, Dec. 2, 2022. Wang Gang/VCG)