The Making of Yunnan

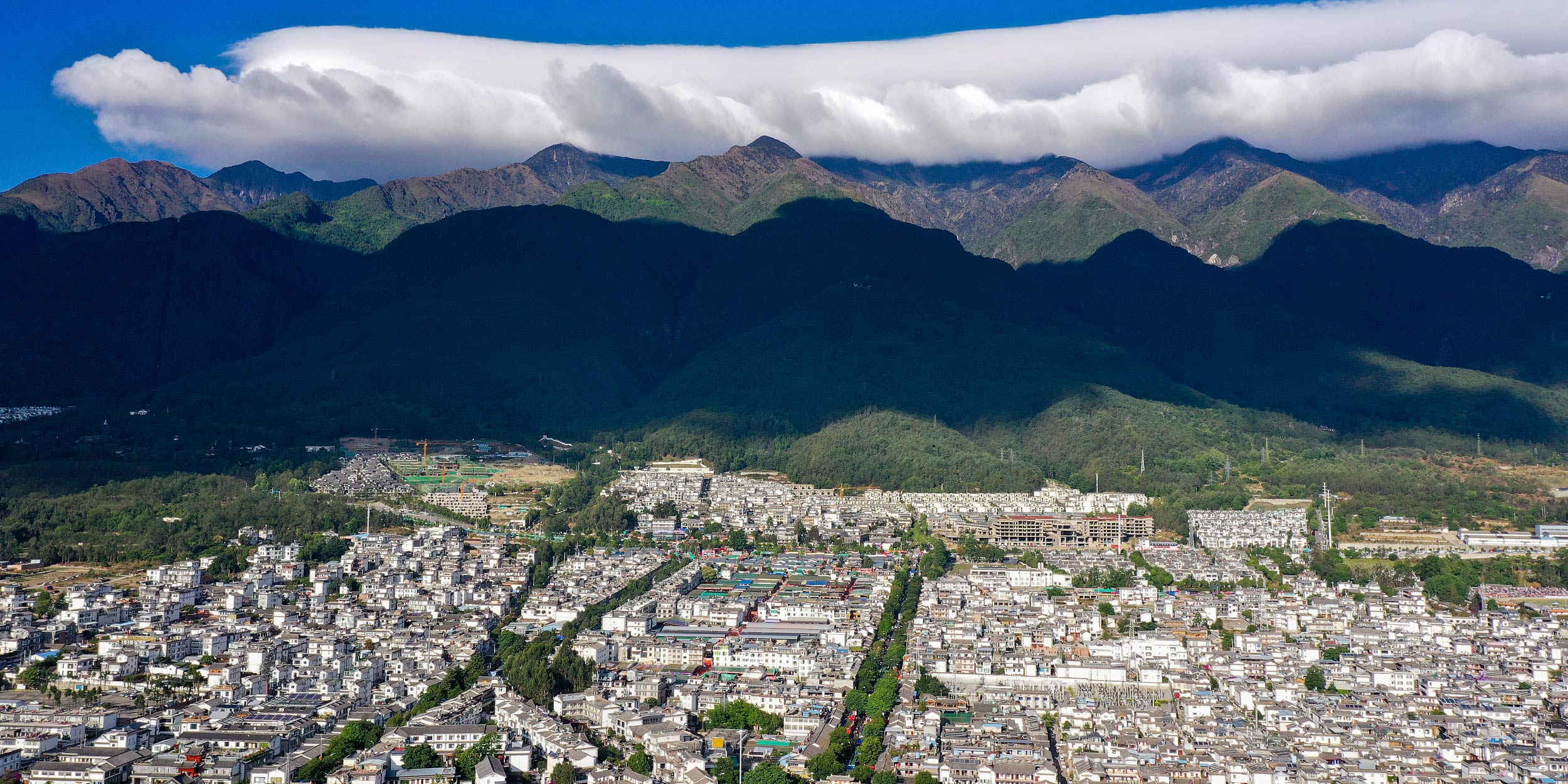

Everyone just wants to move to Dali. The longtime vacationers’ paradise, located in the far southwestern province of Yunnan, became the getaway du jour during the COVID-19 pandemic, as urbanites fled lockdowns for a life of relaxation in the mountains. The phenomenon even spawned a hit TV show, January’s “Meet Yourself,” in which “Mulan” star Liu Yifei quits her white-collar Beijing job, moves to Dali, and falls in love with the slow life.

“Meet Yourself” is far from the only recent pop culture product to romanticize Yunnan. From the mountains of Dali and Lijiang to the jungles of Xishuangbanna, Yunnan is seen across China as a land of pastoral beauty and easy living. Perhaps singer Hao Yun summed it up best in his 2014 song, “Go to Dali”: “Are you unhappy in life? Haven’t laughed for a long time and don’t know why? Go to Dali! Go to Dali! If you’re not happy and you don’t like it here, why not head west, all the way to Dali?”

Unsurprisingly, such idyllic depictions largely obscure the reality of life in Yunnan, one of China’s poorest provinces by GDP per capita, in favor of presenting it as a kind of untouched “Shangri-La.” For their part, Yunnan officials have leaned into the stereotype: In 2001, Zhongdian County won a government-sponsored contest and was officially renamed after the famous secluded city of James Hilton’s 1933 novel “Lost Horizon.” Just as Westerners like Hinton once Orientalized the Far East, contemporary Chinese see Yunnan as a beautiful, exotic “other.”

Yang Bin, a graduate of Northeastern University and currently head of the University of Macau’s Department of History, has spent much of his career pushing back against these stereotypes and attempting to unearth the real history of Yunnan’s people and cultures. His 2009 book “Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan,” translated into Chinese by Han Xiangzhong in 2021, sparked controversy in Chinese academic circles for its unorthodox approach to the region: Instead of using anthropology or ethnography to situate Yunnan’s diversity within the “greater Chinese family,” Yang used a frontier studies approach more common to the study of regions like Xinjiang.

Speaking with Sixth Tone from Macau, Yang shared his thoughts on Yunnan’s unique history, the importance of border regions to state formation, and what other scholars have missed about Yunnan’s past. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sixth Tone: Anyone who travels to Yunnan is immediately struck by its diversity. From the Tibetan north to the tropical south, it is home to more officially recognized ethnic minorities than any other province. How did this diversity come about?

Yang Bin: It’s a function of Yunnan’s topography. The Yunnan Plateau is the southeastern tail of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Going from northwest to southeast, the altitude gradually decreases and the climate ranges from cold to temperate, subtropical and tropical. In addition, several major rivers within Yunnan, including the Jinsha River, divide Yunnan into distinct sections. This combination of terrain and climate factors inevitably led to diversity in living environments, economic life, and thus cultural, social, and ethnic diversity.

But I want to emphasize that Yunnan is more culturally complex and diverse than even its terrain might suggest. It exists between Southeast Asian and Indic cultures in the south, Tibetan culture in the west, and Han Chinese culture in the east. You won’t find that unique mix anywhere else in Asia. In order to truly understand Yunnan, it is necessary to examine its history and culture.

Sixth Tone: Yunnan has a long history, from the ancient Dian kingdom (278 B.C.-109 B.C.) and the Nanzhao kingdom (A.D. 738-902) to eventually becoming a part of China. But much of early Yunnan history is overlooked in China. What period of Yunnan’s past do you wish more people would study?

Yang: I’d probably say the Dali kingdom (937-1253) period. Its duration was equivalent to the two Song dynasties (960-1279), and it ruled over much of present-day Yunnan and Guizhou provinces, as well as parts of what is today the “Golden Triangle” where Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meet.

The Dali kingdom was fascinating. On the one hand, it was highly Sinicized. The country’s official religion was Chinese Buddhism, and its elites used Chinese characters and adopted China’s political system. On the other hand, there were few political contacts between the Dali kingdom and the Song dynasty. In fact, the Song deliberately adopted an attitude of isolation from Dali, and even refused the kingdom’s request to become a Song tributary. In the entire “History of Song,” the official dynastic history compiled in the 14th century, only around 600 words deal with Dali. It’s just incredible.

Sixth Tone: Why do you think that happened?

Yang: It’s probably due to the Han Chinese tendency to center the north in history. From the Qin dynasty (221 B.C.-226 B.C.) to the Song, Chinese dynasties seemed to feel that the ethnic groups and kingdoms from the north were more important, and they weren’t particularly interested in the southwest. They believed the best way to maintain peace along the southwestern frontier was simply by not interacting with the kingdoms there. In the “History of Song,” there are very detailed records of the Liao, Jin, and Xia, but only a brief sketch of Dali. This mentality still more or less exists today. Academics have done a lot of research on northern peoples, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, the Khitans, and others, but there are few monographs on the Dali kingdom.

I mentioned that the Dali kingdom was fairly Sinicized, but it also established a very close economic and cultural relationship with Southeast Asia. For example, as I explore in “Cowrie Shells and Cowrie Money: A Global History,” its adoption of the cowrie money system could be seen as linking it to the economic circle of the Bengal region.

Sixth Tone: Speaking of Southeast Asia, can you say a little about its impact on Yunnan?

Yang: First, we need to clarify that the contemporary concept of “Southeast Asia” only came into being after World War II. What is called “Southeast Asia” today was previously divided into three parts, from north to south: the upper region, including what are today the southwestern Chinese province-level regions of Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi; the Southeast Asian mainland; and the surrounding islands. Of these three, the region Yunnan was most closely tied to in ancient times was the mainland — today’s Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, and northeastern India.

Yunnan, especially the southern and southwestern regions, is closely related to mainland Southeast Asia in terms of geography, climate, ethnicities, economy, religion, and politics. Before the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), China had relatively little influence in the region. That was true until the mid- to late-Ming, when the situation began to reverse, and China’s influence gradually increased.

Sixth Tone: Chinese are taught that the Mongols destroyed the Dali kingdom and incorporated Yunnan into the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), making Yunnan a part of China. Is that correct?

Yang: The Mongols did indeed bring Yunnan under their control. But historically, the region had been conquered multiple times by northern dynasties, and as soon as those northern dynasties disintegrated, it became independent once again. I’d argue that Yunnan was not truly included in China’s jurisdiction until the Ming, when Han immigrants gradually penetrated its mountains and border areas.

Of course, there are scholars who do not agree with this viewpoint. Some Chinese scholars adopt a northern-centric — and thus Han-centric — view, marginalizing Yunnan’s cultural dynamics and oversimplifying the process by which Yunnan was transformed from a frontier area to a province of China. They have ignored, deliberately or not, Southeast Asian and Indic connections and influences in Yunnan’s development.

Sixth Tone: The Ming, like the Song, was founded by Han Chinese. Why did the rulers of the Ming attach more importance to the southwest than the Song?

Yang: Because they didn’t want to face the same predicament as their forebears. The Southern Song (1127-1279) faced repeated Mongol attacks from the north. After the Mongols defeated and occupied Dali, the Song found their southwestern flank exposed. When Zhu Yuanzhang established the Ming Dynasty, Yunnan was actually still in the hands of the Mongols. So, Zhu made a decision to take over Yunnan, and he adopted a series of measures after the conquest to incorporate Yunnan into the Ming.

During this period, the Sinicization of indigenous people in Yunnan occurred in parallel to the indigenization of the Han Chinese who entered Yunnan. The Ming focused on promoting Confucian education in Yunnan, especially among the region’s elite. Meanwhile, Han Chinese immigrants adapted to local norms and practices: they engaged in mining, learned local languages, and married locals. Han immigrants imitated the clothing of indigenous peoples and also accepted their customs and religious rituals. Sinicization in Yunnan was very successful in comparison to other border areas, but this was largely a result of unofficial contacts between peoples — immigration and intermarriage foremost among them — and not top-down planning.

Sixth Tone: As a border area, how relevant was Yunnan to the rest of China?

Yang: What I tried to emphasize in “Between Winds and Clouds” is that the border shapes the center, and at times even saves the center. For empires, it is not the center that determines the border, but the border that determines the center.

For instance, in the 18th century, the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) faced a copper shortage. Copper coins were the only legal tender in China, but the Qing did not have enough copper material and could only import copper from Japan. In 1715, the Japanese shogunate began to control its metal exports, exacerbating the shortage. In response, the Qing government began vigorously mining copper in Yunnan, and, as a result, Yunnan copper gradually replaced foreign copper as the source of Qing coinage. From the Qianlong to Jiaqing periods (r. 1735-1820), Yunnan produced almost 10 million jin of copper annually. About 6 million jin of that was sent to Beijing every year. It was precisely because of Yunnan copper that a unified and empire-wide currency market emerged. You could say that without Yunnan and its copper, the most prosperous century of Qing rule would never have happened.

Sixth Tone: After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, what have been some of the unique features of the PRC’s approach to border management in Yunnan?

Yang: The American anthropologist Stevan Harrell argued that China’s southwestern border was influenced by three “civilizing” forces: the Confucian Chinese empire, the Catholic Church of the missionaries, and the “New China” founded in 1949.

In terms of the latter, the most unique aspect of PRC governance might be its emphasis on “ethnic identification.” Since 1950, the Chinese government has identified various ethnic groups within its borders. These identifications are based on its interpretation of Marxism, with the aim of integrating minorities into the “Chinese national family.” Yunnan became a key area for this work due to its ethnic diversity. In my opinion, this ethnic identification work has not been solely guided by Marxism. Rather, to a large extent it represents a continuation and development of the heritage of imperial China. Yunnan, as the province with the most ethnic minorities, is a symbol of a harmonious, multi-ethnic China.

Translator: Matt Turner; editor: Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A view of Dali, Yunnan province, May 4, 2023. VCG)