The Forgotten Story of China’s First Orchestra

When Shanghai’s T’ou-Sè-Wè Museum opened a new exhibit on the city’s history of music education on May 18, it may not have expected the show’s star attraction to be a simple, faded black-and-white photo from the 1850s.

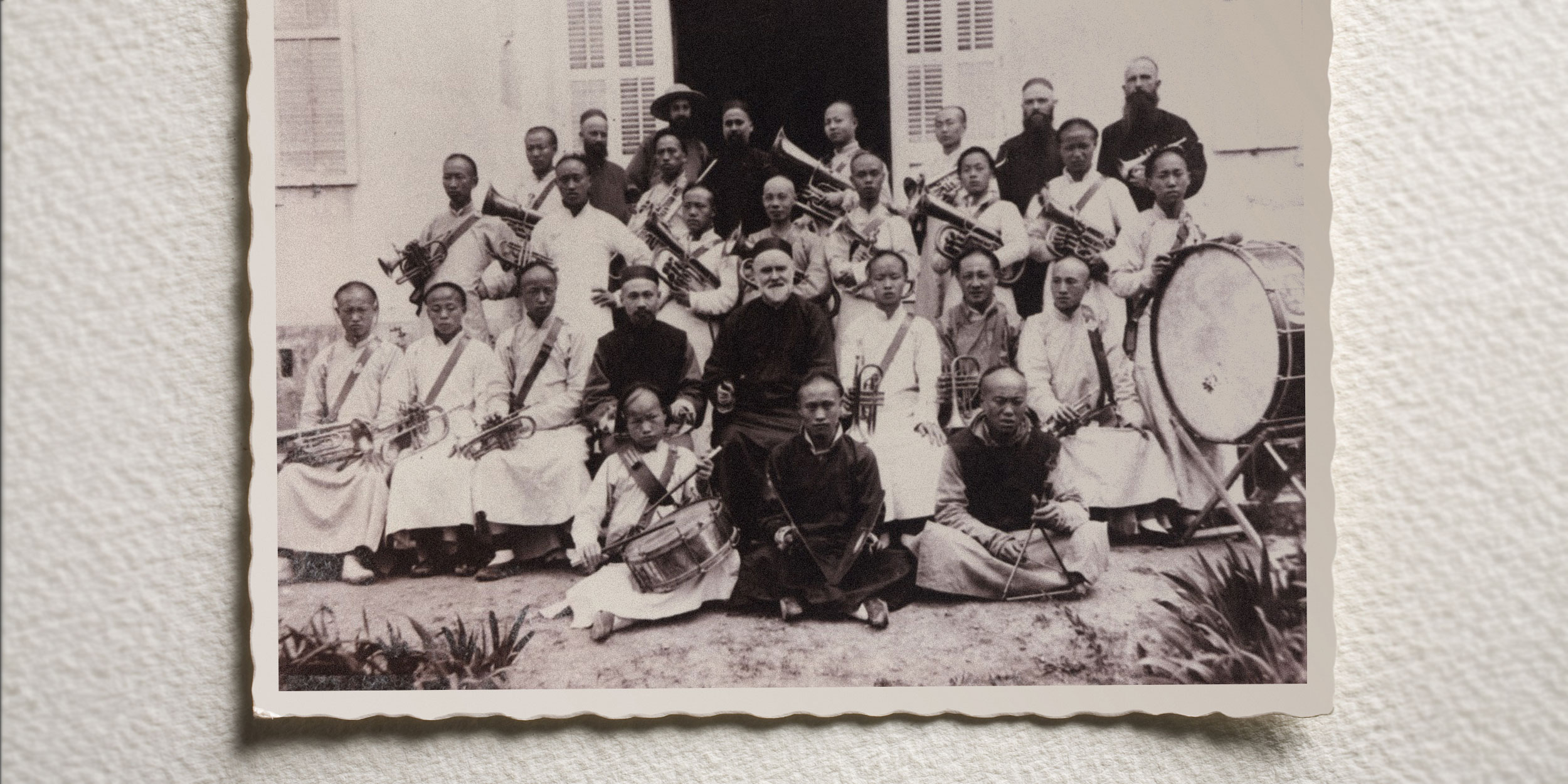

At first glance, the photo seems ordinary: 21 Chinese boys ranging from children to young adults stand in a big group, all of them dressed in jackets typical of the late Qing dynasty (1644-1912) period. Then you notice the items in their hands: Western musical instruments like triangles, horns, and oboes. Finally, you spot the man at the center of the crowd. His face obscured by the instruments, he could pass for one of the boys but for his beard and European features.

The man was French Jesuit missionary François Ravary; the boys were members of the orchestra he founded at Collège St. Ignace, in Shanghai’s Xujiahui neighborhood. And the photograph, taken in the late 1850s, was forgotten for over a century until it was unearthed and highlighted in David Francis Urrows’ 2021 book on Ravary: “François Ravary SJ and a Sino-European Musical Culture in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai.” Now, it’s rewriting the history of Western music in China.

Until recently, there was no scholarly consensus on how or when the introduction of Western music into modern China took place. Some traced it to the formation of the Shanghai Public Band (now the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra) in January 1879, which was headed by Jean Rémusat — “Europe’s premiere flautist” — and composed largely of Filipino musicians. Others argued that Sir Robert Hart’s brass band, founded in 1885, should be considered the earliest Western orchestra in China because its members were Chinese. And a few pointed instead to a music course taught by American missionaries at Shandong’s Tengchow College in 1876.

Now, it’s clear that Ravary’s band had them all beat.

According to Urrows, Ravary arrived at Collège St. Ignace in 1856 and was quickly put in charge of the school’s choir. Aspiring to “teach Western music in a Chinese environment,” he decided to establish a wholly Chinese orchestra.

There was just one problem: He had no instruments. So Ravary turned to his good friend, a violinist-turned-Jesuit named Hippolyte Basuiau, who shipped him a variety of instruments from Europe.

In addition to those imported instruments, Ravary also made his own. Together with fellow Jesuits Louis Hélot and Léopold Deleuze, he set up a workshop in what was then St. Ignatius Church. The trio then recruited four Chinese carpenters to help them build a pipe organ out of bamboo.

Hélot was responsible for calculating the dimensions of the bamboo pipes, while Ravary produced the sketches that Deleuze and the Chinese carpenters used in their work. Eight months later, they had their instrument: a unique bamboo pipe organ modeled after the sheng, a Chinese folk instrument consisting of vertical pipes. Pleased, Ravary declared in a letter that, “Only an artistic eye could discern that the keys did not come from a European workshop.”

This first organ was installed in the Dongjiadu Catholic Church in 1857. Deleuze and a team of Chinese workers later built another organ, this time with three special keys to reproduce the sound of Chinese folk instruments: the xiao (vertical flute), di (transverse flute), and sheng (mouth-blown organ). They dedicated it to the son of Napoléon III, then the king of France. It is now preserved at the Musée de la Musique in Paris, though the bamboo pipes have rotted and can no longer produce sound.

Once his instruments were ready, Ravary began recruiting Chinese students to take lessons in Western music. In 1864, when a group of orphans was moved near the school in advance of the opening of T’ou-Sè-Wè orphanage, he included them in his orchestra training as well.

On the morning of Nov. 22, 1864, the band left Xujiahui for the first time and performed a few marches in the international concession area. This all-Chinese Western orchestra received polite praise from the concession crowd and was recognized by the French Consul, but Ravary saw room for improvement. “It is fortunate that in this country, people’s ears are not as discerning as they are on the Champs-Élysées,” he wrote in a letter. Once the performance ended, the nervous student-musicians gorged themselves on steamed buns.

A later performance, in 1871, went better. Baron Joseph Alexander von Hübner of Austria listened to the ensemble at the T’ou-Sè-Wè orphanage and was seemingly impressed by the novelty. “Haydn played in China by the Chinese! ... We were all deeply moved.”

Two years later, the administrative units of the Collège St. Ignace and the T’ou-Sè-Wè orphanage split. The former retained only its internal string orchestra, which required far fewer members. Ravary was also transferred out of Xujiahui during this period, and the school’s remaining Jesuits, who were generally not as fond of the orchestra as he was, let it fade into obscurity.

There it would have remained, if not for the intervention of Francisco Diniz. A Shanghai-born Macanese, Diniz and his friends organized a military band at the T’ou-Sè-wè orphanage in 1903 known as the Fanfare de Saint Joseph. In order to teach Western music more systematically, Diniz and Joseph Tsang co-edited a textbook on the subject written in Shanghai dialect. At just over 70 pages, the book used a question-and-answer format to teach students how to play wind instruments like trumpets and tubas. The book is China’s earliest known textbook on Western instrumental music and the earliest such textbook written in the Shanghai dialect.

Although Fanfare de Saint Joseph was only ever an amateur school club, its members’ skill garnered it invitations to play at various events around the city. Whenever Chinese and foreign dignitaries came to Xujiahui, the band would inevitably appear.

The members of Diniz’s T’ou-Sè-Wè band were never paid for their performances. Nevertheless, they cherished their time rehearsing and performing. Near the end of his life, Li Chenglin, a T’ou-Sè-Wè orphan who died in 2009, could still recall the French names of the instruments in interviews.

In 1907, Louis Hermand, a Western music teacher who worked with the band, predicted that, “In a few decades ... we will see a Chinese child take their place among masters like [Charles] Gounod and [Richard] Wagner.” That never quite happened, but for a brief time, musicians like Li made beautiful music all the same.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editor: Wu Haiyun; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: A group photo of The Tou-Se-We band. Francisco Diniz can be seen sitting in the second row, fourth from left. Courtesy of the author)